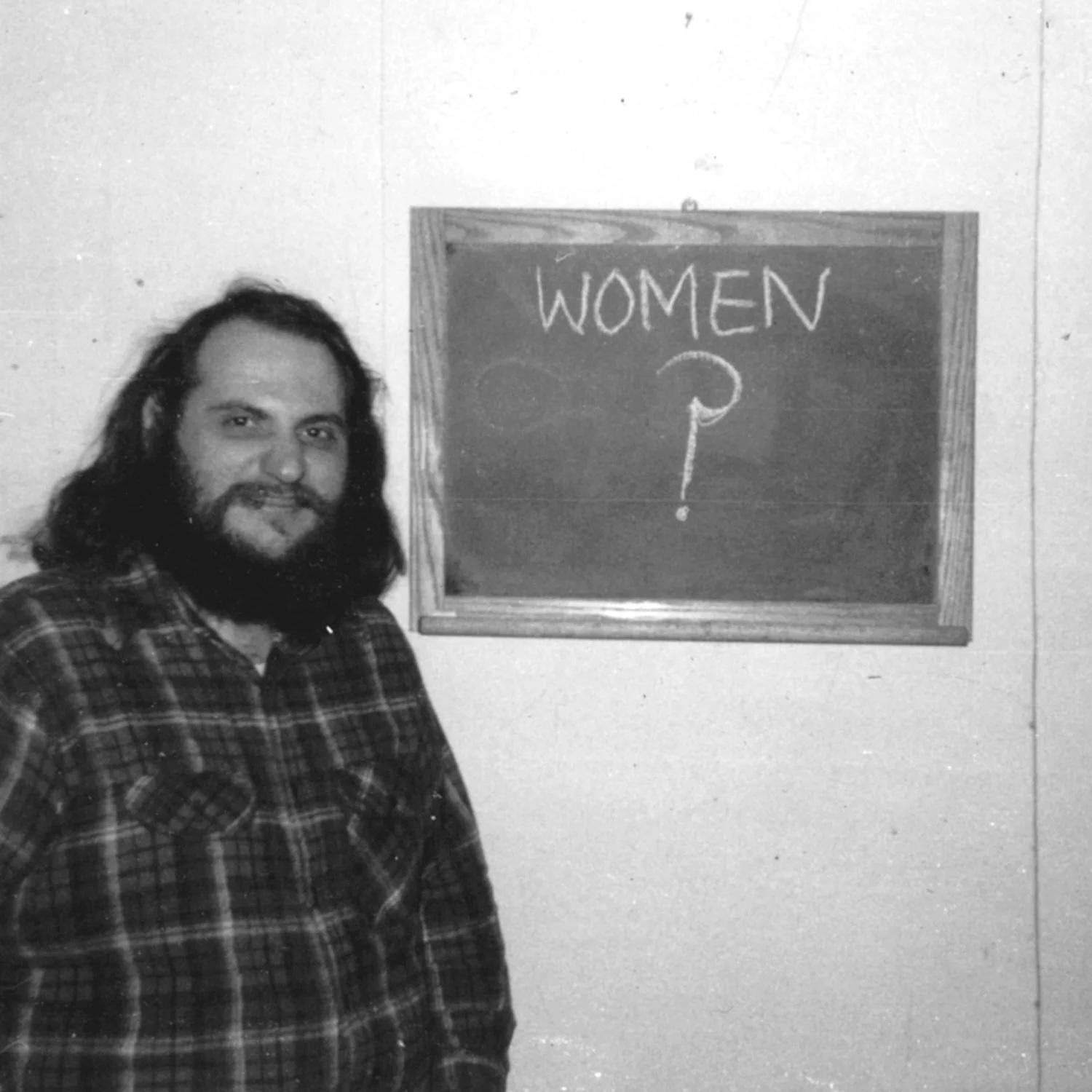

Picture a folding table in a college hallway in 1973. Hand-lettered sign. Stack of index cards. A young artist asks passing students to do something disarmingly simple: write one word describing the opposite sex.

It sounds like a party game. In reality, it was a quiet X-ray of the gender politics of the early 1970s. The artist later posted the results online: men and women, asked the same question, produced very different words. Some were affectionate. Some were hostile. Many were telling.

In 1973, asking people to describe the opposite sex in a single word turned into an accidental survey of sexism, fear, desire, and confusion. The words people chose reflected second-wave feminism, the sexual revolution, and the backlash brewing against both.

Here are five big things that little pile of index cards can tell us about that moment in time, and why it still hits a nerve today.

1. The power gap showed up in the adjectives

The simplest pattern in projects like this is also the most blunt: men tended to describe women as objects or roles, while women tended to describe men as power. That is, men’s words pointed at how women looked or what they did for others. Women’s words pointed at what men had and what they could do to you.

In early 1970s America, that tracks with the broader culture. In 1972, Playboy was selling millions of copies a month. Airline ads still called flight attendants “stewardesses” and sold them as eye candy. The Miss America pageant, protested by feminists in 1968, was still a prime-time ritual. Women were legal adults, but the language around them sounded like packaging copy.

So when men in a 1973 art project reached for a single word, a lot of them landed on things like “beautiful,” “soft,” “emotional,” or less printable versions of “sexy.” Those words weren’t neutral. They echoed the way women were framed in ads, sitcoms, and even workplace memos.

Women, by contrast, were living with a very different reality. In 1973, the Supreme Court had just decided Roe v. Wade, but there was still no federal law banning workplace sex discrimination in practice, and marital rape was legal in every state. Men were the bosses, the professors, the cops, the husbands with legal authority over credit cards and mortgages.

So women’s one-word answers about men often skewed toward “controlling,” “selfish,” “dominant,” “strong,” or “aggressive.” Even when the words were positive, they tended to be about power and agency, not appearance. Men were “ambitious” or “decisive”. Women were “pretty” or “fragile.”

Language about the opposite sex in 1973 mirrored the power imbalance of the time. The fact that men reached for looks and softness while women reached for control and strength shows how each group experienced the other in daily life.

2. Second-wave feminism was in the room, even if no one wrote “feminist”

By 1973, second-wave feminism was no longer fringe. Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique had been out for a decade. Ms. magazine had launched in 1971. The Equal Rights Amendment passed Congress in 1972 and went to the states. That movement shaped the mental furniture of everyone walking past that art table, whether they liked it or not.

On those index cards, that influence showed up sideways. Some men wrote words like “threatening” or “confused” about women. Some women wrote “oppressed” or “awakening” about men, meaning: men were waking up to women’s anger, or women were waking up to men’s power. The exact words from the original project vary, but this pattern is common in similar 1970s surveys and consciousness-raising group notes that historians have studied.

Take 1970’s Women’s Strike for Equality, organized by the National Organization for Women (NOW). Tens of thousands of women marched for equal pay, childcare, and abortion rights. Newspaper coverage often framed them as shrill, unfeminine, or man-hating. That media framing bled into how ordinary men talked about women who demanded equality. “Bitchy” and “castrating” started showing up in letters to the editor and, unsurprisingly, in private comments.

On the flip side, women’s words about men in 1973 were shaped by consciousness-raising groups. In those living-room meetings, women compared experiences of harassment, unequal housework, and patronizing bosses. Men stopped being just “husbands” or “boyfriends” and became “oppressors” or “sexists” in the shared vocabulary of the movement.

So when a woman in 1973 wrote a single word about men, she was not answering in a vacuum. She was answering after reading Gloria Steinem in Ms., after hearing about the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, after watching Phyllis Schlafly organize against the ERA. The word on the card was a tiny echo of a very loud national argument.

The presence of feminism and anti-feminism in those one-word answers shows that even casual language about the opposite sex was already politicized. The art project caught people mid-argument about what men and women should be.

3. The sexual revolution made everything more blunt

The early 1970s were the hangover and the high point of the sexual revolution. Birth control pills had become widely available in the 1960s. Hair and Cabaret were on Broadway. Porn theaters were moving from the shadows to Times Square marquees. People were talking about sex in public in ways their parents would have found unthinkable.

That shift showed up in how people described the opposite sex. A 1950s version of this project might have produced words like “mysterious” or “proper.” By 1973, you were more likely to see “horny,” “tease,” “easy,” or “animal.” The language got more explicit because the culture had.

Look at 1972’s hit film Last Tango in Paris, or the 1972 court decision in Miller v. California trying to define obscenity. Debates about what counted as pornography, art, or just adult entertainment were everywhere. The line between “respectable” and “dirty” was being redrawn in real time.

Men describing women in one word often leaned into this new frankness. Some wrote words that reduced women to body parts or sexual availability. Women, for their part, sometimes described men as “users” or “pigs,” reflecting the downside of the sexual revolution: men who treated “free love” as a license to pressure women, without much concern for their safety or reputation.

At the same time, a minority of answers from both sexes used words like “equal,” “partner,” or “friend.” That hinted at a different sexual ethic emerging, one based on mutual respect rather than conquest or purity.

The sexual revolution made people more willing to use blunt, sexualized language about the opposite sex. That bluntness exposed the gap between the ideal of free, equal pleasure and the reality of who still held the power in sexual relationships.

4. Stereotypes were gendered, but they were also generational

One easy mistake when looking at a 1973 project like this is to assume “men” and “women” were unified blocks. They were not. A 19-year-old male art student and a 55-year-old male professor might both write a word about women, but they were drawing from very different worlds.

The early 1970s sat on a fault line between the World War II generation and the baby boomers. The older cohort had grown up with Rosie the Riveter propaganda and then a swift return to 1950s domesticity. The younger cohort had grown up with Vietnam protests, Woodstock, and Janis Joplin.

So when older men described women, they often leaned into words like “homemaker,” “mother,” or “dependent,” reflecting the breadwinner/housewife model they had been sold. Younger men, especially in college settings, were more likely to say “liberated,” “confusing,” or “demanding” about women. They were meeting women who expected to have careers, control their fertility, and argue back.

Women’s words about men split along similar lines. Older women, many of whom had married young and stayed home, might write “provider” or “protector.” Younger women, facing male professors who hit on them or boyfriends who quoted Marx but expected them to do the dishes, might choose “hypocritical” or “chauvinist.”

Think of the generational clash inside the 1970s sitcom All in the Family. Archie Bunker, the working-class patriarch, uses blunt sexist and racist language. His daughter Gloria and son-in-law Mike challenge him with feminist and anti-war arguments. That dynamic played out in real families, and in the words people chose about the opposite sex.

So when we look at a single word on an index card from 1973, we are not just seeing “what men thought of women” or vice versa. We are seeing what a particular 20-year-old or 40-year-old, shaped by a particular set of experiences, could say in a public hallway without blushing.

The generational split in those one-word answers reminds us that gender attitudes were changing unevenly. Age, class, and subculture mattered as much as biological sex in shaping how people saw each other.

5. The project itself showed how art was turning into social research

There is one more layer here that often gets missed: the fact that this was a conceptual art piece, not a Gallup poll. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, artists were increasingly using surveys, instructions, and participation as their medium. They were less interested in painting a picture of gender than in making you feel your own assumptions.

Think of Yoko Ono’s 1964 “Cut Piece,” where audience members were invited to come on stage and cut off pieces of her clothing. Or Adrian Piper’s early 1970s works, where she handed out cards confronting people with their racist or sexist behavior. These pieces turned social interaction into the artwork.

The 1972–73 “write one word about the opposite sex” project sits in that tradition. The artist was not just collecting data. They were staging a small social experiment. The act of choosing a word, in public, with the artist watching, was part of the piece.

That context matters. People might have censored themselves, or leaned into shock value, because they knew it was “art.” A man might write a more provocative word than he would say to his mother. A woman might choose a sharper word than she would use at work, because the art space felt safer.

At the same time, the artist’s decision to present the results decades later on Reddit turned a 1970s conceptual piece into a 21st-century conversation starter. Thousands of people, many born long after 1973, read those words and compared them to their own.

Conceptual art projects like this blurred the line between art and social science. By asking ordinary people to supply the content, they captured raw attitudes that historians and readers can still learn from.

Why those 1973 words still matter

On the surface, a stack of index cards from 1973 with single words about the opposite sex looks like a curiosity. But when you place it in context, it becomes a snapshot of a society in mid-mutation.

The words men used for women reveal how much women were still seen as bodies and caretakers, even as they marched for equal rights. The words women used for men reveal how clearly they saw the power imbalance, and how much frustration simmered beneath polite surfaces.

Today, if you ran the same project on a campus or a city street, you would get a different mix of words: more “nonbinary,” more “ally,” more “toxic,” more “kind.” But you would still see power, fear, desire, and resentment threaded through the answers. The conversation has changed, but it has not ended.

That is why this small 1973 conceptual art piece still resonates online. It reminds us that gender is not just about laws or theories. It is about the snap judgments and one-word labels we carry around in our heads, and how those labels shape the way we treat each other.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the 1973 “write a word about the opposite sex” project?

It was a conceptual art piece started in 1972–73 where an artist asked men and women to write a single word describing the opposite sex on index cards. The collected words, later shared online, reveal how people in that era casually thought and talked about gender.

What do the 1973 opposite-sex words tell us about sexism?

They show that men often described women in terms of appearance and emotional traits, while women more often described men in terms of power and control. That pattern mirrors the legal and social inequalities of the early 1970s, when men held most formal authority in work, law, and family life.

How did second-wave feminism affect how people described the opposite sex?

By 1973, second-wave feminism had made ideas like “sexism” and “oppression” part of public debate. Women’s words about men reflected growing anger at unequal treatment, while some men’s words about women showed anxiety or hostility toward women’s demands for equality.

Why do people still find this 1973 gender word project interesting?

It compresses a whole era’s gender politics into blunt, one-word judgments. Readers today can instantly compare those 1970s attitudes to their own, which sparks curiosity, debate, and a sense of how much has changed and how much has not.