PHOTO: wideopenspaces.com

Last time on History’s Badasses, we covered the woman known as the “Spanish Joan of Arc”: Agustina of Aragon. She was just your average girl living during the 1800s, but her great courage against the impossible odds of Napoleon’s invasion of Spain inspired thousands of Spanish soldiers to fight for victory.

This time, we’ve got an all-American badass for you by the name of Hugh Glass. His story has been immortalized in popular legend and in two feature-length films. The first: Man in the Wilderness (1971), the second: The Revenant (2015), starring Leonardo DiCaprio in a performance that would win the actor an Academy Award, BAFTA, and Golden Globe. The movies retell the incredible story of Hugh Glass’ survival after being left for dead by his companions and attacked by a grizzly bear in the South Dakotan wilderness. He trekked 200 miles to Fort Kiowa on his own, without supplies or weapons, and eventually made it home.

Early Life

PHOTO: myfavoritewesterns.com

Not very much is known about Hugh Glass’ early life. He was born in Pennsylvania sometime in 1783 to Scots-Irish immigrants from Ulster, in what is now present-day Northern Ireland.

Most of the stories we have about his early life come from popular legend. The stories go that he was captured by pirates in 1816 and spent two years with them. He escaped by swimming to shore on the coast of Texas. Other stories say he was captured by the Pawnee tribe, lived with them for many years, and eventually married a Pawnee woman.

What we do know is that, in 1821, when he was about 38 or so, Hugh Glass arrived in St. Louis with several Pawnee delegates who had been called there to meet with representatives from the United States government.

Tangling With a Grizzly Bear

PHOTO: sdpb.org

His real story began in 1822. General William Henry Ashley had put an advertisement in the Missouri Gazette and Public Advertiser. The ad was looking to hire a corps of one-hundred men to “ascend the river Missouri” in a fur-trading venture. Many famous mountain men joined, including John Fitzgerald, David Jackson, and Jedediah Smith.

The group was traveling up the Missouri in 1823. They were scouting around at the forks of the Grand River, near the Shadehill Reservoir in South Dakota, looking for game. Glass was minding his own business with the rest of the group when he accidentally disturbed a grizzly bear, a mother grizzly bear, to be specific, with two cubs.

She charged, bit him, mauled him, and pinned Glass to the ground. Still, with the help of his expedition members, he managed to kill the bear. He was left horrifically mauled and unconscious. General Ashley didn’t think he would survive.

The General asked two volunteers to stay with Glass. They would wait for him to die and then give the man a proper burial. Two men stepped forward, named Fitzgerald and Bridger. They dug Hugh’s grave as the party moved on down the river.

Supposedly, a group of Arikara, a tribe affiliated with the Mandan and Hidatsa, swooped down on the pair and attacked them. That’s what Bridger and Fitzgerald told the party when they caught up with them later, anyway. They’d abandoned Hugh Glass, taken his rifle, knife, and other equipment, and left him to die.

All Glass knew when he woke up was that he was abandoned, left without any sort of weapons, food, or equipment. His leg was broken, his scalp was ripped open, his throat was punctured, his wounds were festering, and he was 200 miles from the nearest American settlement: Fort Kiowa.

What did he do? Did he lay there and die? Not Hugh Glass!

Running on sheer power of will, Glass was determined not to die. He set his own leg, wrapped himself in the only thing his comrades had left him: a bear skin by way of burial shroud, and began crawling on his hands and knees to Fort Kiowa.

PHOTO: historynet.com

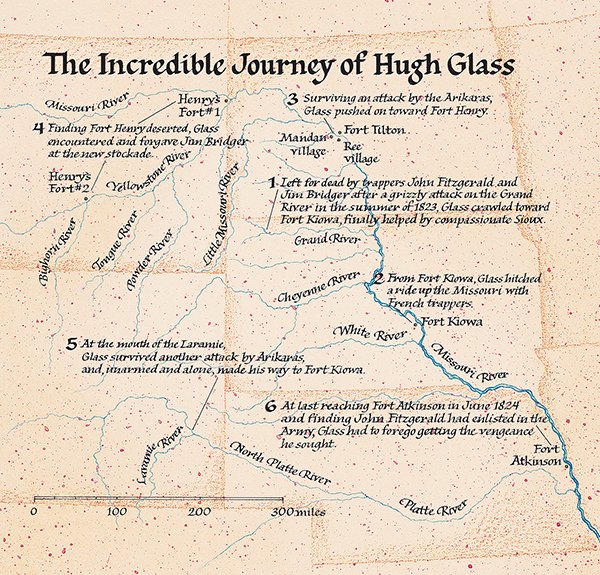

It would take him six weeks. Thunder Butte was his landmark. From there, he crawled south to the Cheyenne River, where he managed to throw together a raft. He floated downstream to Fort Kiowa, surviving on wild berries and roots.

To prevent gangrene from his infected wounds, he let maggots eat the dead flesh. Despite his injuries, he drove two wolves away from a bison calf. That day, he ate as much of the raw meat as he could.

On his way down, he met a group of friendly Native Americans. They harbored him for a night, sewed a bear hide directly onto his back to cover his exposed wounds, and gave him food and weapons.

Eventually, he made it to Fort Kiowa. Glass shored up there and recovered from his wounds, but once he was recovered, he wasn’t finished. He set out to hunt down the two men that had abandoned him.

He found Bridger, but the story goes he forgave him because he was just a kid. Fitzgerald was a little less lucky. He found Fitzgerald at Fort Atkinson in Nebraska and made him return his rifle. Glass spared the man’s life, but told him that if he ever left the army, he’d kill him.

Other Stories

You’d think that Hugh Glass would have had his fill of exploration after such an adventure, but he didn’t. He returned to Ashley’s Hundred and, in 1824, set out to discover a new trapping route.

During the trip, they were attacked by Arikara. Two of the party were killed. Glass survived by hiding behind some river rocks. He got back to home base at Fort Kiowa by joining a band of Sioux and traveling home with them.

Death

Hugh Glass spent the rest of his life as a trapper and fur trader. In 1833, he was killed by Arikara on the banks of the Yellowstone River. His story has been popularized in legend and myth as a testament to courage against impossible odds, and the power of the human spirit to survive in the face of danger.