Anne Brontë was the youngest member of the Brontë family. Born in 1820, she only lived to be twenty-nine, dying in 1849. She and her sisters, Charlotte and Emily, published a volume of poetry in 1846 under pseudonyms. In 1847, Brontë published Agnes Grey, followed by the Tenant of Wildfell Hall in 1848, which still remains to be one of the first sustained feminist novels. She published all her novels and poems under the name of Acton Bell.

On January 17, 1820, Anne Brontë was born outside of Bradford at 74 Market Street. She was the youngest of Maria Branwell and Patrick Brontë’s six children: Maria (1814-1825), Elizabeth (1815-1825), Charlotte (1816-1855), Patrick Branwell (1817-1848), Emily (1818-1848), and Anne (1820-1849). On March 25, 1820, Anne was baptised in Bradford. Shortly after, her father was appointed to the perpetual curacy in a small town a few miles away, Haworth. The Brontë family moved to Haworth to a five-roomed house that would remain their home for the rest of their lives.

Before Anne was even a year old, her mother Maria Branwell is believed to have gotten uterine cancer. She became ill and died on September 15, 1821. Patrick tried to marry to find a mother for his young children, but was unsuccessful. So, Elizabeth Branwell, Maria’s sister, moved in with them to raise the children. Elizabeth had originally been there to nurse her sister. Instead of love, she respected respect from the children and had little affection with the older ones. According to tradition though, Anne, the youngest, was her favorite of the family.

In 1824, Anne’s sisters were all sent to Crofton, West Yorkshire to attend Crofton Hall and then then to Lancashire for the Clergy Daughter’s School. However, Patrick’s two eldest daughters died of consumption the following year. Marie died on May 6 and Elizabeth followed on June 15. Immediately, he had Charlotte and Emily sent home. Patrick was so distressed after the deaths of not only his wife a few years before, but then his daughters that he could not bear to send away his children again. He and Elizabeth Branwell mainly educated the children at home instead for the next five years. Anne’s personality and religious beliefs may have been influenced by her aunt Elizabeth, who she was close with and also shared a room with.

The Brontë children were all close friends, as they relied on each other instead of making friends outside of their parsonage. They would play on the moors around Haworth.

The Keighley church organist taught Anne, Emily, and Branwell piano. John Bradley gave them art lessons. Their aunt Elizabeth taught the girls to run a household. She was met with limited success, as the three girls were far more literary inclined. Thanks to their father’s library, they were introduced to works of literature by authors such as Byron, Homer, Milton, Scott, Shakespeare, Virgil, and more. They also read the Bible and articles from BlackWood’s Edinburgh Magazine, Fraser’s Magazine, and The Edinburgh Review. The children also read books on history and geography along with several biographies.

When Branwell was presented with a set of toy soldiers in June of 1826 by their father, the imaginative children’s’ creativity grew even more. Not only did they name each soldier, but they also developed personalities for all of them. They created an African kingdom called “Angria”, illustrated with maps and other watercolor pieces. The Brontë children came up with clever little plots for those who lived in Angria and Glass Town, the capital of the kingdom.

Anne and Emily split away from Charlotte and Branwell around 1831 so they could create their own fantasy world, which they called Gondal. When Charlotte had left that January for Roe Head School, Anne became even closer to Emily. Ellen Nussey, a friend of Charlotte’s, visited Haworth in 1833, describing Emily and Anne as “like twins” that were “inseparable companions.” She also described Anne and said that she was their aunt’s favorite. When Charlotte returned from Roe Head, she also began to give Anne lessons. In July of 1835 she went back to Roe Head to teach. Emily went with her to attend the school. But as Emily was unable to adapt to living at school away from home, Anne took her place.

Anne was fifteen when she left for Roe Head. It was her first time to leave home and she had a hard time making friends. The quiet and hardworking fifteen year old was determined to stay at the school though so she could get an education to support herself later on. For two years she remained at the school, only going back home at Christmas and during the summer. In December of 1836 she even won a good-conduct medal. It seems that Anne and Charlotte were not all that close when they were at Roe Head. Rarely did the elder sister mention the younger in her letters. Charlotte was, however, concerned about her sister’s health when Anne became ill in in 1837. Before that December, she had gotten gastritis and also went through a religious crisis. She was visited many times by a Moravian minister who suggested the reason she had become distressed and ill was because of conflict with the local Anglican clergy. Charlotte had quickly written to their father, who brought her home to recover.

A year after Anne had left Roe Head, the nineteen year old sought out a position as a teacher. She needed to earn herself a living because her poor, clergyman father could not support her. When he died, the parsonage would also go bake to the church. At the time, being a teacher or governess were some of the very limited options for poor, educated young women.

So, in April of 1839, Anne began work as a governess. She worked for the Ingham family, living at Blake Hall not too far from Mirfield. The Ingham children were spoiled and rarely listened. Anne fought hard to control them and was essentially unsuccessful at educating them. When she would complain about the childrens’ behavior, she was met with no support from anyone. She was not allowed to punish them. The inghams criticized her for not being capable and had her dismissed, also unsatisfied with the progress Anne had made with their children. Not even a year had passed when she returned home that Christmas to join her sisters and brother.For Anne, the episode at Blake Hall had been traumatizing. She almost perfectly reproduced it in Agnes Gray, her future novel.

William Weightman was one of her father’s new curates when Anne returned home. He was twenty-five at the time and had gotten a two-year theology licentiate from University of Durham. it is possible that Anne may have fallen in love with, but there is little evidence of this besides an anecdote used in January of 1842 by Charlotte. Also, there were a number of poems that paralleled her acquaintance to Wightman. Her character Edward Weston in Agnes Grey seemed to be similar to Weighton. Weston was the one who fell in love with the main character, Agnes Grey, of Brontë’s novel. Weightman died of cholera in 1842 and Anne mourned his loss in a poem.

After the unsuccessful job at Blake Hall, Anne became a governess again to Reverend Edmund and Lydia Robinson’s children at their country home Thorp Green Hall, which is near York. There, Anne was employed for five years from 1840-45. The Robinson’s had four children that Anne taught, fifteen year old Lydia, thirteen year old Elizabeth, twelve year old Mary, and eight year old Edmund. In Agnes Gray, their house was reimagined as Horton Lodge. At first, Anne had seemed to be met with similar problems to when she worked at Blake Hall. She deeply missed her family and home. In 1841, she wrote that she wished to leave the position. Anne was still determined to keep going and soon became more successful. The Robinson’s quite liked her as well. And the Robinson daughters, her charges, would stay lifelong friends.

The only time Anne spent with her family while she was the Robinson’s governess was during Christmas and summer holidays in June. With the exception of those 5-6 weeks, her time was spent at Thorp Green. At the time, Anne and her sisters even thought about opening their own school, but it never materialized. Anne decided to go back to working at Thorp Green after.

Elizabeth Branwell, Anne’s aunt whom she had formed a close relationship with, died in November of 1842. Anne had immediately gone back home while her other sisters were in Belgium. Elizabeth had left all three of her nieces £350, which is equivalent to £30,000 as of 2015.

The following January, Anne returned to Thorp Green and secured a position as a tutor for the Robinson’s son, Edmund, for her brother Branwell. Unlike Anne, Branwell did not live in the house.Branwell did enter a secret relationship with Lydia Robinson, his employer’s wife. Though all of the Brontë sisters worked as governesses or teachers at one point, facing problems with their charges, Anne was the only one to become successful out of it due to her perseverance.

Anne wrote a three verse poem called Lines Composed in a Wood on a Windy Day in 1842 at Thorp Green. She published it in 1846 under her pen name Acton Bell.

In June of 1846 while Anne was at home on holiday, she resigned from her position. She did not gave the Robinson’s a reason as to why, but there is speculation that it was because she had found out about her brother’s relationship with Lydia Robinson. There is no real evidence to this though. Soon after, Branwell was also dismissed because Edmund Robinson found out about his relationship with his wife. Anne still retained a close relationship with her employer’s daughters, Elizabeth and Mary Robinson. They exchanged many letters. In December of 1848 ,the Robinson sisters came to visit their old governess.

Emily accompanied Anne on a trip to some of her favorite places she had discovered as the Robinson’s governess. They had planned to visit Scarborough, but that fell through. Instead, the two sisters visited York and York Minster.

The Brontë sisters were all at home during the summer of 1845 with no plans for employment. During this time, Charlotte discovered poems Emily had written and only shown to Anne about the world Gondal. Charlotte proposed they publish their poems. When Anne showed Charlotte her poems, she was not met with as much enthusiasm. Still, the sisters decided to write a collection of poetry, not telling anyone, including their father and Branwell. While Anne and Emily both wrote twenty-one poems, Charlotte wrote nineteen. They used the money their aunt had left them to publish the collection.

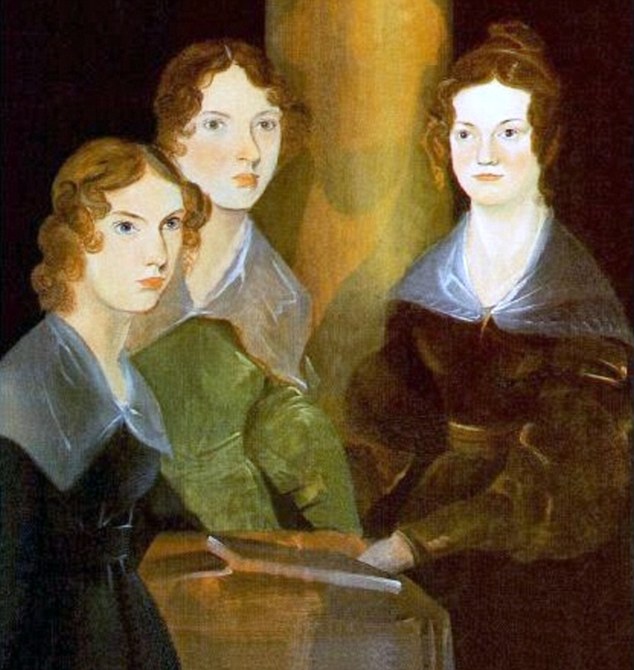

At the time, women did not often publish literary works and were met with different reactions. The sisters decided to write the collection under male pen names. They took their initials to create Currer (Charlotte), Ellis (Emily), and Acton (Anne) Bell (Brontë). It was published and available for purchase in May of 1846. The collection was met with only somewhat good reviews, but ended up being a failure. They only sold two copies the first year. Anne was able to publish her poem “The Narrow Way” in two magazines in December of 1848 under the pen name and was met with more success.

Before they had published their poems, the sisters had all began working on their own novels. While Charlotte wrote The Professor and Emily Wuthering Heights, Anne set to working on Agnes Grey. They had all finished the manuscripts by July of 1846 and sent them to publishers in London.

Nearly every publisher but Thomas Cautley Newby denied Anne and Emily’s novels. Charlotte’s was rejected by all though. Still, the eldest Brontë sister finished Jane Eyre, which Smith, Elder & Co accepted right away. It was also the first to be published while the other two sisters’ novels “lingered in the press”. Jane Eyre was an instant success. Anne and EMily’s publisher noticed Charlotte’s success and then published their novels in December of 1847. Both books sold quite well, but Agnes Grey seemed to outshine Wuthering Heights.

Anne published The Tenant of Wildfell Hall in late June of 1848. The book did extremely well, selling out in only six weeks. It remains to be one of the most shocking contemporary Victorian novels. Anne depicted alcoholism and debauchery in a profoundly disturbing way, but she did this because she wanted to write about the truth. It is also known for it’s portrayal of the position of women during Anne’s time.

In August of 1848, the second edition of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall appeared in which Anne wrote about her intentions of writing the book. This is what she said:

“When we have to do with vice and vicious characters, I maintain it is better to depict them as they really are than as they would wish to appear. To represent a bad thing in its least offensive light, is doubtless the most agreeable course for a writer of fiction to pursue; but is it the most honest, or the safest? Is it better to reveal the snares and pitfalls of life to the young and thoughtless traveller, or to cover them with branches and flowers? O Reader! if there were less of this delicate concealment of facts–this whispering ‘Peace, peace’, when there is no peace,there would be less of sin and misery to the young of both sexes who are left to wring their bitter knowledge from experience.”

Charlotte and Anne traveled to London in July of 1848 because of the rumor that the “Bell Brothers” were actually just one person. Emily had refused to accompany her sisters. There, they revealed their identities and their gender to George Smith, Charlotte’s publisher. As their own novels became increasingly popular, their collection of poems was resurfaced when George Smith bought it, though it still did not sell well.

For the previous two years, Branwell’s health had been declining. He was constantly drunk, using this to cover up the seriousness of his illness. On September 24, 1848, thirty-one year old Patrick Branwell Brontë died, a shock to the whole family. It was recorded that he died of chronic bronchitis, though today historians believe it had really been from tuberculosis.

During the next winter, the whole family suffered from various coughs and colds. Emily, however, became very ill. Over the course of the next two months, her health got worse and worse. She refused all medical help until December 19, feeling as weak as ever. But it was two loot. She died later that evening at thirty years old.

Anne was deeply affected by her sister’s death. The two had been extremely close. She caught the flu over Christmas. As she got worse, her father had a physician come in January. Anne was diagnosed with consumption, or tuberculosis, that had been quite advanced. There was little hope and chance of her recovering. But Anne was determined. She took her medicine and followed advice from the doctor, also writing her final poem about being terminally ill.

In February, Anne seemed to be recovering and decided to return to Scarborough. She hoped that the fresh sea air could possibly help her recover. Charlotte did not want her sister to go, but the doctor approved it. On May 24, 1849, Anne, Charlotte, and Ellen Nussey left. Little did she know that would be the last time saying goodbye to her father.

When they arrived in Scarborough, Anne had to be escorted in a wheelchair by Charlotte. They did some shopping and visited York Minster. At that point, it was clear to all that Anne had hardly any strength. A few days later on Sunday May 27, Anne asked her sister if it would be better if they returned to Haworth to die. They met with a doctor the next day who said she was going to die soon. Charlotte was deeply distressed. Anne expressed her love for her sister and Ellen. Before she died, Anne told her sister to “take courage”.

On May 28, 1849, a Monday, Anne Brontë died around 2 p.m. in Scarborough at twenty-nine years old. Charlotte decided to bury her sister in Scarborough instead of with the rest of the family in Haworth. Two days later, they held a funeral, but patrick was unable to complete the journey in time. The only mourner at the funeral was a former Roe Head schoolmistress.

Charlotte Brontë, the last of the Brontë children. would die a few years later on March 31, 1855 at thirty-eight when she was pregnant. The recorded cause of death was tuberculosis, but it is now believed to have been from dehydration and malnutrition due to morning sickness. Patrick Brontë died on June 7, 1861. He outlived his wife and all six of his children.