On 25 September 2022, Italians woke up to a result many outside the country found shocking. The party with neo-fascist roots, Fratelli d’Italia, led by Giorgia Meloni, had just won the largest share of the vote. Commentators rushed to say: “Italy has gone far right.”

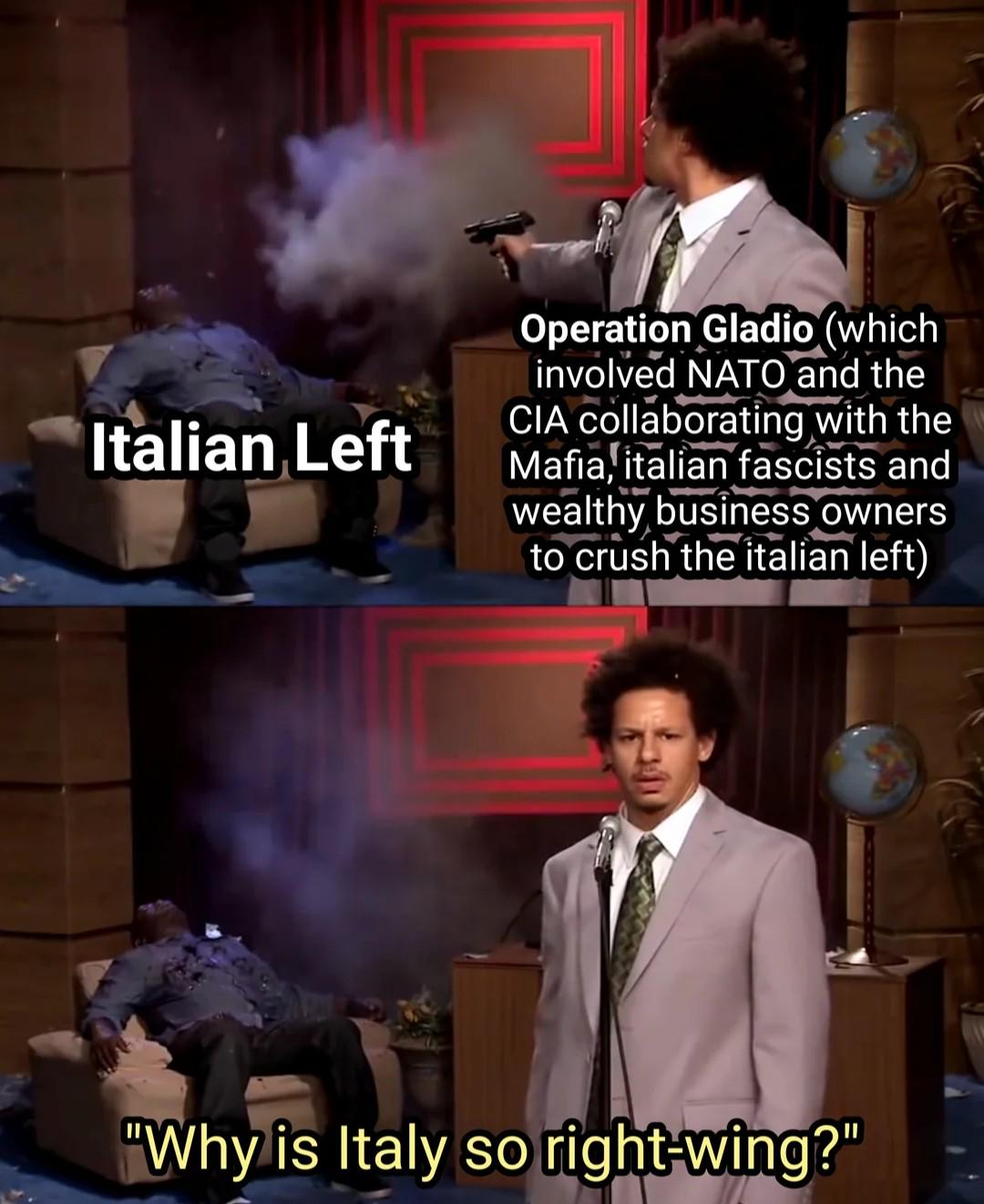

For a lot of Reddit readers and casual observers, the question followed naturally: why is Italy so right wing? Why this country, of all places, keeps producing figures like Mussolini, Berlusconi, and now Meloni.

The short answer is that Italian politics has been shaped by a long fight between fear of chaos and fear of tyranny. Five big historical forces pushed many Italians to see order, tradition, and strong leaders as the safer bet.

1. Mussolini, Fascism, and the Myth of “He Made the Trains Run on Time”

What it is: Italy was the first country to have a mass fascist regime. Benito Mussolini’s rule from 1922 to 1943 did not just impose dictatorship. It also left behind a powerful myth that authoritarian right-wing rule brings order and national pride.

In October 1922, Mussolini’s Blackshirts marched on Rome. King Victor Emmanuel III, terrified of civil war, invited Mussolini to form a government instead of sending in the army. Within a few years, opposition parties were banned, unions were crushed, and a one-party state was in place.

The regime pushed a simple story: before Mussolini, Italy was weak, divided, and humiliated. Under fascism, Italy was strong, disciplined, and respected. The slogan was everywhere: “Mussolini ha sempre ragione” – Mussolini is always right.

The famous line that “Mussolini made the trains run on time” is half myth, half propaganda. Some railway improvements started before he took power. But the regime hammered home the idea that only a firm, nationalist right could fix Italy’s chaos and inefficiency.

A concrete example of this myth-making came with the 1936 invasion of Ethiopia. The war was brutal and illegal under international law, but at home it was sold as Italy finally taking its “rightful place” as an empire. Crowds filled Rome’s streets as Mussolini announced victory from the Palazzo Venezia balcony. For many Italians, especially those who benefited from jobs and contracts, fascism looked like national revival.

Of course, the reality was darker: repression, censorship, racial laws against Jews in 1938, and disastrous entry into World War II on Hitler’s side. By 1943, the country was invaded, bombed, and collapsing. Mussolini was overthrown, then shot by partisans in 1945.

Yet the memory of fascism stayed complicated. Some Italians remembered dictatorship and war. Others remembered order, full employment propaganda, and a sense of national pride. That split memory made it easier for right-wing parties after 1945 to tap into nostalgia without openly praising fascism.

Why it mattered: Being the original fascist state left Italy with a deep cultural script: strong, nationalist right-wing rule is what you turn to when democracy feels weak and chaotic. That script never fully disappeared, so it kept resurfacing in later crises.

2. The Cold War: Anti-Communism as a National Habit

What it is: After World War II, Italy became a front-line state in the Cold War. It had the largest communist party in Western Europe, the Partito Comunista Italiano (PCI), and a powerful Catholic, anti-communist party, Democrazia Cristiana (DC). For decades, politics was organized around fear of communism, which pushed many voters and institutions toward the right.

In 1948, the first big postwar election turned into a global showdown. The United States poured money and propaganda into supporting the Christian Democrats. The Soviet Union backed the communists and socialists. Priests warned from pulpits that a communist victory meant the end of religion and private property.

The DC won, and for the next forty years, it dominated Italian governments. Even when the left did well in votes, the PCI was kept out of national power. The reason was simple: NATO and the Vatican did not want a communist-led government in a country that hosted key American bases and sat across from the Soviet-backed states of Eastern Europe.

Concrete example: the “Historic Compromise” of the 1970s. PCI leader Enrico Berlinguer tried to move his party toward Eurocommunism, accepting democracy and NATO, and proposed cooperation with the Christian Democrats. Even then, full entry into government never happened. The fear of a communist party in charge was too strong in Washington, in Rome, and in parts of Italian society.

Anti-communism filtered into everyday life. In many families, especially in the countryside and small towns, voting left was seen as dangerous or immoral. The right and center-right could always say: whatever our flaws, at least we are not communists.

That habit survived even after the Soviet Union collapsed. In the 1990s and 2000s, Silvio Berlusconi constantly warned that his opponents on the center-left were “ex-communists” who would raise taxes, threaten business, and bring back class conflict.

Snippet-ready line: The Cold War turned Italian anti-communism into a reflex, which kept pulling voters toward conservative and right-wing parties long after the Soviet Union vanished.

Why it mattered: Decades of defining politics as “us or the communists” made right-leaning choices feel like the safe, normal option. That long habit helped later right-wing leaders present themselves as protectors against any leftward shift, even when the old communist threat was gone.

3. The First Republic Collapses, and Berlusconi Fills the Void

What it is: In the early 1990s, a huge corruption scandal called Tangentopoli (“Bribesville”) blew up Italy’s old party system. The traditional center and center-left parties collapsed. Into that vacuum stepped Silvio Berlusconi, a billionaire media owner who built a new right-wing coalition around TV, marketing, and fear of the left.

In 1992, magistrates in Milan began investigating bribes in public contracts. The scandal spread fast. Dozens of politicians were arrested or investigated, including leaders of the Christian Democrats and Socialists. Voters watched nightly news reports of handcuffed officials and suitcases of cash.

By 1994, the old parties were discredited. Berlusconi, who owned major private TV networks and publishing houses, launched Forza Italia, a new party named after a football chant. He presented himself as the successful businessman who knew how to create jobs and fight bureaucracy.

Concrete example: the 1994 election. Berlusconi stitched together a right-wing alliance that included the post-fascist Alleanza Nazionale and the regionalist, anti-immigrant Lega Nord. He used his TV channels to flood the airwaves with campaign ads and talk shows favorable to his side. He warned that if the left won, “the communists” would ruin the economy and threaten personal freedoms.

He won. Berlusconi would go on to serve as prime minister in three separate periods (1994–95, 2001–06, 2008–11), making him one of the longest-serving leaders in republican Italy.

His governments cut some taxes, softened labor protections, and defended traditional family values. They also passed laws that critics said were tailored to protect his business interests and shield him from legal trouble. But for many voters, especially small business owners and middle-class Italians, he was the man who spoke their language against “red judges,” unions, and Brussels bureaucrats.

Snippet-ready line: The collapse of Italy’s old parties in the 1990s opened the door for Silvio Berlusconi, whose media-powered right-wing politics reshaped the country for a generation.

Why it mattered: Berlusconi normalized a modern, media-savvy right that mixed business-friendly policies, cultural conservatism, and anti-elite rhetoric. He made voting right-wing feel like the default for millions of Italians who were angry at corruption but wary of the left.

4. North–South Divide, Economic Anxiety, and the Search for Order

What it is: Italy has long been split between a richer, industrialized north and a poorer, less developed south. Add chronic unemployment, slow growth, and waves of migration, and you get a society where many people feel insecure. Right-wing parties have been very good at turning that insecurity into votes.

Since unification in the 19th century, the “Questione Meridionale” (Southern Question) has haunted Italian politics. Northern elites complained that the south was backward and corrupt. Southerners complained that the state ignored them and treated them like a problem to be managed.

In the postwar decades, millions of southerners moved north to work in factories in Turin, Milan, and Genoa. That migration helped build Italy’s economic boom in the 1950s and 1960s, but it also created resentments. Northern workers and small business owners saw newcomers as competitors and as proof that the state was failing to develop the south.

Concrete example: the rise of the Lega Nord in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The party, led by Umberto Bossi, started as a northern regionalist movement that mocked the south as a drain on taxpayers. It talked about “Padania,” a mythical northern nation, and demanded federalism or even secession. The party’s message was simple: Rome and the south waste your money, we will defend your region.

Later, under Matteo Salvini, the Lega dropped “Nord” from its name and turned into a national right-wing party. It shifted focus from attacking southerners to attacking migrants, especially from Africa and the Middle East. The underlying formula stayed the same: blame outsiders and a weak state for economic and social problems.

Economic stagnation after the 2008 financial crisis made this message even more powerful. Youth unemployment in Italy has often been above 30 percent. Many young Italians leave for jobs in Germany, the UK, or elsewhere. Those who stay see precarious work, low wages, and little faith that mainstream parties will fix anything.

In that setting, right-wing parties promise clear enemies and simple solutions: stop migrants, cut taxes, punish criminals, defend “our people.” For voters who feel exposed and ignored, that can sound more convincing than technocratic plans or calls for patience.

Why it mattered: Long-term economic divides and insecurity made large parts of Italian society receptive to messages about order, identity, and protection. Right-wing parties learned to channel those fears into lasting electoral support.

5. From Neo-Fascist Fringe to Giorgia Meloni’s Mainstream Right

What it is: After World War II, the heirs of Mussolini’s party survived on the margins. Over decades, they rebranded, moderated some positions, and waited. By 2022, their political descendants, led by Giorgia Meloni, had become the leading force in Italian politics.

In 1946, former fascists formed the Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI). It never got close to power nationally, but it kept a small, loyal base, especially among veterans, some middle-class conservatives, and parts of the south. For many Italians, MSI was a reminder that the fascist past was not entirely buried.

In the 1990s, as the old party system collapsed, MSI leaders tried to clean up their image. Under Gianfranco Fini, they created Alleanza Nazionale (AN), dropped the most explicit fascist symbols, and accepted democracy and NATO. Fini even visited Israel and condemned the racial laws of 1938.

Concrete example: the 1994 alliance with Berlusconi. AN joined Berlusconi’s first government, giving the post-fascist right its first taste of national power in the republic. That move helped normalize the idea that parties with fascist roots could be part of respectable coalitions.

Giorgia Meloni came out of this world. She was a youth activist in the post-fascist movement, then a minister in Berlusconi’s government in 2008–2011. In 2012, she broke away to form Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy), a small party that kept the old tricolor flame symbol linked to MSI.

For years, Fratelli d’Italia was minor. Then came a series of crises: the eurozone debt crisis, austerity, migration across the Mediterranean, and the COVID-19 pandemic. While other right-wing parties joined technocratic or unity governments, Meloni stayed in opposition. She attacked the European Union, defended “God, family, and nation,” and presented herself as the only consistent voice on the right.

By the 2022 election, that strategy paid off. Fratelli d’Italia won about 26 percent of the vote, making it the largest party. Meloni formed a government with Salvini’s Lega and what remained of Berlusconi’s Forza Italia.

Her government has tightened migration policies, emphasized traditional family values, and taken a tough line on “gender ideology,” while staying relatively cautious on economic policy and NATO. She rejects the label “fascist” and insists her party is a conservative, patriotic right. Critics point to the party’s symbols, some members’ statements, and its roots to argue that the line with the far right is thin.

Snippet-ready line: Giorgia Meloni’s rise shows how parties with post-fascist roots moved from the fringe to the center of Italian politics by mixing nationalism, social conservatism, and anti-elite rhetoric.

Why it mattered: The success of Fratelli d’Italia confirmed that a hard-edged, nationalist right is not a temporary protest but a stable option in Italian politics. It closed a long arc that began with Mussolini and passed through postwar neo-fascism, Berlusconi, and the Lega.

So why does Italy look so right wing today? Because a century of history trained many Italians to see the right as the answer to chaos, communism, corruption, and insecurity. That does not mean Italy is a fascist country, or that the left has vanished. It does mean that the right, in its various forms, has had more practice at turning fear and frustration into power.

The legacy is visible every time an Italian election becomes a choice between order and risk, tradition and change, “us” and “them.” Those patterns were not born on Reddit. They were built in streets marched by Blackshirts, in Cold War ballot boxes, in Berlusconi’s TV studios, and in the rallies of Giorgia Meloni.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is Italy considered right wing today?

Italy is seen as right wing today because parties on the right have dominated recent elections, especially Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia, which won the largest share of the vote in 2022. This reflects long-term factors like anti-communism, distrust of old centrist parties, economic insecurity, and the normalization of nationalist, conservative politics since the 1990s.

Is Italy more right wing than other European countries?

Italy is one of several European countries where right-wing or far-right parties have entered government, alongside places like Hungary and Poland. What makes Italy stand out is its history as the first fascist state and the way post-fascist and nationalist parties have become central players rather than staying on the fringe. That said, Italy still has significant center-left and left-wing parties and a competitive political system.

Did Mussolini make Italy permanently right wing?

Mussolini did not make Italy permanently right wing, but his regime left a strong cultural memory that authoritarian, nationalist rule can bring order and pride. After 1945, many Italians rejected fascism, yet some nostalgia for the supposed stability of that era survived. Later right-wing parties could tap into that memory indirectly, especially during periods of crisis or political chaos.

How did Berlusconi change Italian politics?

Silvio Berlusconi changed Italian politics by creating a modern, media-driven right-wing coalition after the old party system collapsed in the early 1990s. He used his TV networks and business image to present himself as an outsider who could fix corruption and defend ordinary people from the left. His success made right-wing, personality-centered politics a normal feature of Italian democracy and helped pave the way for later figures like Matteo Salvini and Giorgia Meloni.