Picture a crowd in a Sicilian city around 550 BC, pressed into a sun‑baked square. In the center stands a life‑sized bronze bull, gleaming and hollow. A prisoner is forced through a side door. The opening is sealed. Wood is piled beneath the belly and lit. As the metal heats, the man inside begins to scream. Through a system of tubes in the bull’s head, his cries emerge as a bellowing roar.

That is the famous story of the Brazen Bull of Phalaris, the tyrant of Acragas (modern Agrigento) in Sicily. Ancient writers said an Athenian craftsman named Perillos built it in the 6th century BC. The victim roasted to death inside while the crowd heard “a bull” roar. It is one of antiquity’s most quoted torture devices, and also one of the most doubted. Many historians suspect it is either exaggerated or outright invented as anti‑tyrant propaganda.

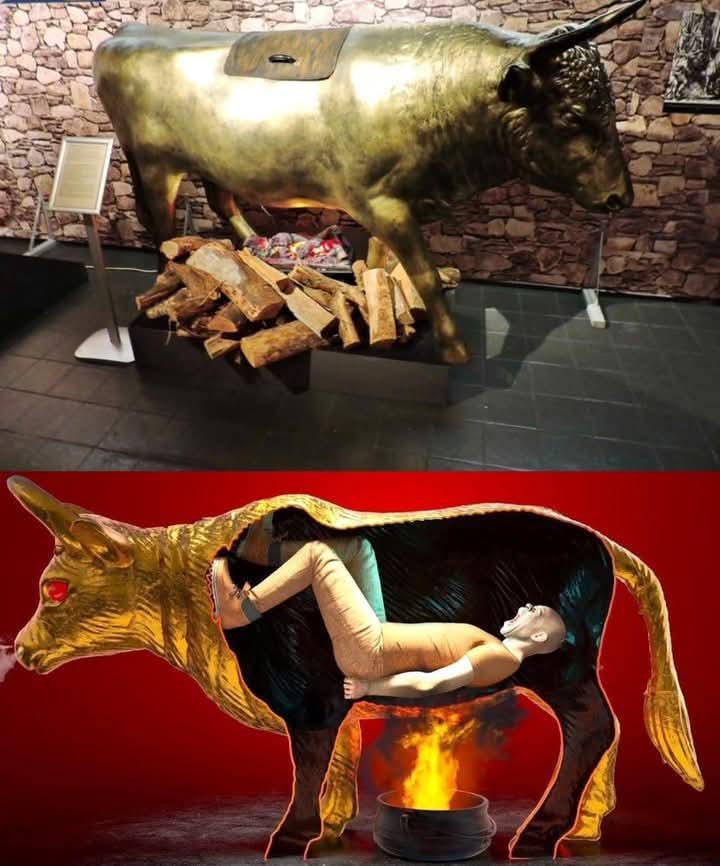

The brazen bull was supposedly a hollow bronze statue used to burn victims alive, with pipes that turned screams into bull‑like sounds. Ancient sources describe it as both execution device and theatrical spectacle. Whether it existed or not, the story shaped how later ages imagined ancient cruelty.

So what if the brazen bull had been real, and not just real, but widely adopted? What would that have meant for Greek politics, technology, and the way later societies punished and terrified people? To answer that, we need to start with what we actually know about Phalaris, Acragas, and the problem of ruling a city full of enemies.

Was the brazen bull of Phalaris even possible?

First, the physics. Could a 6th‑century BC Greek city have built such a thing?

Bronze casting at that time was advanced. Greek artisans already produced life‑size and larger statues using the lost‑wax method. A hollow bronze bull, perhaps 2–3 meters long, was well within technical reach. A door cut into the flank and re‑sealed with a latch or bolts is also plausible. The idea of sound‑shaping tubes is not far‑fetched either. Simple acoustic devices were known in the ancient world, and a set of curved pipes could distort and amplify sound.

The real constraint is heat. To kill a human by roasting inside a bronze shell, you need sustained, intense fire. That means a lot of fuel. Acragas sat above fertile land, with access to wood from inland Sicily. For a one‑off execution, that is manageable. As a regular device, it becomes expensive and logistically annoying. Wood cost money. Labor to build the pyre cost money. Tyrants liked terror, but they also liked cash.

Then there is the politics. Phalaris, who ruled Acragas in the mid‑6th century BC, appears in sources as a stereotypical cruel tyrant. Later authors, especially in the Roman era, piled on horror stories about him. The brazen bull fits that pattern a little too well. It is theatrical, memorable, and morally neat. Phalaris orders it built, then, in some versions, he ends up roasted in it himself when the people overthrow him. That is the kind of story moralizing writers love.

So the device was technically possible, but the story around it smells like propaganda. That tension sets up our counterfactual. If we assume the bull was real and used, we are imagining a world where one of antiquity’s most notorious torture stories was not just rumor but a working tool of power. That shift in status, from legend to routine, would change how Greek cities thought about fear, punishment, and spectacle.

So what? Establishing that the brazen bull was technically and economically feasible means our what‑if is not fantasy, but a plausible fork in ancient political history.

Scenario 1: A real brazen bull, but a local terror only

In the first scenario, the brazen bull exists exactly as the story says, but it stays mostly confined to Acragas and Phalaris’ reign.

Imagine Phalaris in about 560–550 BC. He has seized power in a wealthy Sicilian city that is booming from trade and agriculture. Like other Greek tyrants, he faces aristocratic rivals, potential coups, and popular unrest. He wants a tool that is both punishment and theater. The bull gives him that. Executions are held in public. Enemies, real or imagined, are roasted while the crowd hears the distorted roars. Word spreads through Sicily and southern Italy.

In this version, Greek visitors and exiles carry home stories of the bull. Philosophers and poets use it as a symbol of tyranny’s cruelty. But no one else copies it. Why?

First, Greek political culture had a strong tradition of public, but relatively simple, executions. Stoning, beheading, throwing from cliffs, or poisoning were all cheaper and easier. The bull required a specialist sculptor, a lot of bronze, and constant fuel. For most poleis, it would look like an expensive gimmick.

Second, Greek elites cared about their own dignity. Even tyrants had to worry about how they looked to other cities. A ruler who used a brazen bull too often might be seen as barbaric, more like a Near Eastern despot than a Greek leader. That reputation could hurt alliances and trade.

Third, there is a psychological limit. Spectacular cruelty can backfire. A single shocking execution might cow opponents. A pattern of sadism can unite them. If Phalaris used the bull too frequently, he might accelerate the coalition that overthrows him. That is exactly how later writers framed his fall: cruelty leads to revolt, and he dies in his own device.

In this scenario, the brazen bull is real, but its impact is mostly literary. It becomes a cautionary tale in Greek political thought. Philosophers like Plato and later Roman moralists point to it as the extreme of tyrannical excess. The device itself rusts away after Phalaris’ death, but the story survives, sharpened by the fact that people remember having actually seen it.

So what? A real but localized brazen bull would deepen Greek hostility to tyrants, feeding a political culture that valued law and moderation over spectacular cruelty.

Scenario 2: The brazen bull spreads as a tool of Greek tyrants

Now change one variable. Suppose Phalaris’ brazen bull is not just a one‑off horror, but such an effective tool of intimidation that other rulers copy it.

By the late 6th century BC, tyrannies appear in many Greek cities: Polycrates on Samos, Peisistratos and his sons in Athens, various rulers in Syracuse and other Sicilian colonies. These men already used mercenary guards, exiles, and confiscations to stay in power. In this scenario, some of them also invest in their own bulls.

Why would they? Because the bull turns execution into a public ritual of dominance. It does three things at once:

1) It kills an enemy in a slow, visible way.

2) It sends a sensory shock through the crowd: sight of flames, sound of roars, smell of burning.

3) It creates a story. People who see it will talk about it for years.

Greek tyrants were already aware of the power of spectacle. Polycrates built grand temples and controlled festivals. Peisistratos used religious processions and public works to shape opinion. A brazen bull fits into that toolkit as the dark side of the show.

If bulls appear in a handful of major cities, we get a Mediterranean rumor mill full of very real horror. Merchants from Samos warn Athenians about the tyrant’s bull. Exiles from Syracuse tell stories in Corinth. The brazen bull becomes a recognizable symbol of unaccountable power, like the secret police in a modern dictatorship.

This has knock‑on effects. Anti‑tyrant movements now have a concrete image to rally against. When cities like Athens move toward more participatory government in the late 6th and early 5th centuries BC, reformers can point to the bull as what they never want again. The word “tyrant” in Greek already shifted from neutral to negative over time. In this scenario, that shift happens faster and more sharply, anchored by a shared memory of specific devices of terror.

There is also a technological side. If bulls spread, bronze workers refine the design. Some might experiment with thicker walls for better heat retention. Others tweak the acoustic tubes. You could even see smaller, cheaper versions for individual victims, or larger ones for multiple prisoners. The line between execution and torture blurs further.

So what? A network of real brazen bulls across Greek tyrannies would harden the association between tyranny and sadistic spectacle, pushing Greek cities more strongly toward legal reforms and collective rule as an explicit rejection of such terror.

Scenario 3: The brazen bull becomes a standard of state terror into Roman times

Take the spread one step further. Suppose the brazen bull is not just a Greek tyrant’s toy, but survives long enough to be adopted by later powers, especially Rome.

Rome in the Republic and Empire already used public execution as theater: crucifixion, damnatio ad bestias (being thrown to wild animals), burning, and more. The Romans liked punishments that were visible, humiliating, and symbolically charged. A foreign device with a strong reputation for horror would fit their taste for imported spectacle. They borrowed gods and cults. They could borrow torture technology too.

In this scenario, a Roman governor in Sicily in the 2nd century BC hears local stories about the old bull of Phalaris. He has a new one cast, perhaps as a warning to rebellious slaves or bandits. The story reaches Rome. By the early Empire, a brazen bull appears in an arena as a special execution for a notorious criminal or Christian martyr.

Now the device enters Roman legal and religious memory. Christian writers, already fond of cataloging martyrdoms, seize on the bull as an example of pagan cruelty. Instead of arguing about whether it ever existed, they can point to specific victims. The bull becomes a standard entry in lists of torments, alongside the rack and the stake.

This has two big consequences.

First, the brazen bull shapes the Christian image of Rome and of “the world” as a place of fiery persecution. That could intensify the language of hellfire and punishment in early Christian preaching. When you have a real historical device that roasts people inside a metal shell, it is easy to picture eternal torment in similar terms.

Second, the bull might survive, in some form, into late antiquity and even the early medieval period as a rare but remembered punishment. Instead of being a half‑legend that scholars debate, it would show up in legal codes or church condemnations. Medieval writers would not just repeat a moral story about Phalaris. They would cite actual bulls used by emperors or kings.

That could change how later Europeans thought about ancient cruelty. Instead of treating the brazen bull as a symbol or exaggeration, they would accept it as a standard tool of pre‑modern states. That might normalize a higher level of accepted brutality in punishment debates well into the early modern era.

So what? A brazen bull that survives into Roman and Christian memory would harden historical ideas of state cruelty and could feed more vivid, fire‑centered images of both persecution and divine punishment.

Which scenario is most plausible, and what would really change?

Of these three, the first is the most plausible: a real brazen bull used by Phalaris or another Sicilian tyrant, but not widely copied.

Why? Economics and culture. Bronze was expensive. Fuel was not free. Greek cities already had efficient, terrifying, and much cheaper ways to kill people. They did not need a bronze oven shaped like a bull to make a point. The added theatrical value probably did not justify the cost and risk for most rulers.

Culturally, Greek elites liked to see themselves as more civilized than their neighbors. There was a line between harsh but lawful punishment and what they would label barbaric cruelty. A few tyrants might cross that line. Most would prefer to keep their reputation just this side of monstrous.

So if the brazen bull existed, it was likely rare, a local horror that quickly became a story. That story then grew in the telling. Later writers, especially in the Roman and early Christian periods, loved to pile detail onto tales of ancient cruelty. The pipes that made screams sound like a bull’s roar might be a later embellishment, a way to turn a simple burning into a kind of dark theater.

What would really change if scenario 1 were true? Not the broad arc of history. Greek tyranny would still rise and fall. Athens would still move toward democracy. Rome would still build its empire. But the moral vocabulary of those developments would have a firmer anchor. When philosophers condemned tyranny, they would not be gesturing at a half‑mythical device. They would be pointing to a remembered, specific horror that people’s grandparents had actually seen.

There is one more twist. If the brazen bull was real, it reminds us that the ancient world did not need modern technology to create sophisticated cruelty. A hollow bronze statue, some pipes, and a pile of wood are enough to turn a human body into both victim and sound effect. The fact that we are not sure whether it existed says as much about how stories work as it does about how tyrants ruled.

So what? The most likely version of a real brazen bull would not rewrite ancient history, but it would sharpen our picture of how fear, spectacle, and storytelling worked together in the politics of Greek and Roman power.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did the brazen bull of Phalaris really exist?

Ancient writers describe a hollow bronze bull used by the tyrant Phalaris of Acragas to burn victims alive, but modern historians are divided. The device was technically possible in the 6th century BC, yet the story fits so neatly into anti‑tyrant propaganda that many suspect exaggeration or invention. There is no archaeological evidence of an actual bull, only literary accounts written long after Phalaris’ time.

How was the brazen bull supposed to work?

According to ancient sources, the brazen bull was a life‑size hollow bronze statue with a door in its side. A victim was locked inside and a fire lit beneath it, heating the metal until the person roasted to death. The bull’s head contained tubes or pipes that distorted the victim’s screams so they sounded like the roaring of a bull. The device turned execution into a public spectacle of sound, sight, and terror.

Why would a tyrant use a brazen bull instead of simpler executions?

A brazen bull would have been far more expensive and logistically demanding than hanging or beheading, so it only makes sense as a tool of spectacle. A tyrant might use it to send a powerful message, combining slow, visible suffering with a memorable sound effect to frighten opponents. However, that same theatrical cruelty could backfire by uniting enemies against such a visibly sadistic ruler.

Could the brazen bull have influenced later Roman or Christian punishments?

If the brazen bull had been real and survived into later centuries, it could have been adopted by Roman officials as one more form of public execution. In that case, Christian writers might have cited it as a concrete example of pagan cruelty, feeding vivid images of fiery persecution and hell. In reality, since its existence is uncertain and no physical examples are known, its influence is more literary than legal.