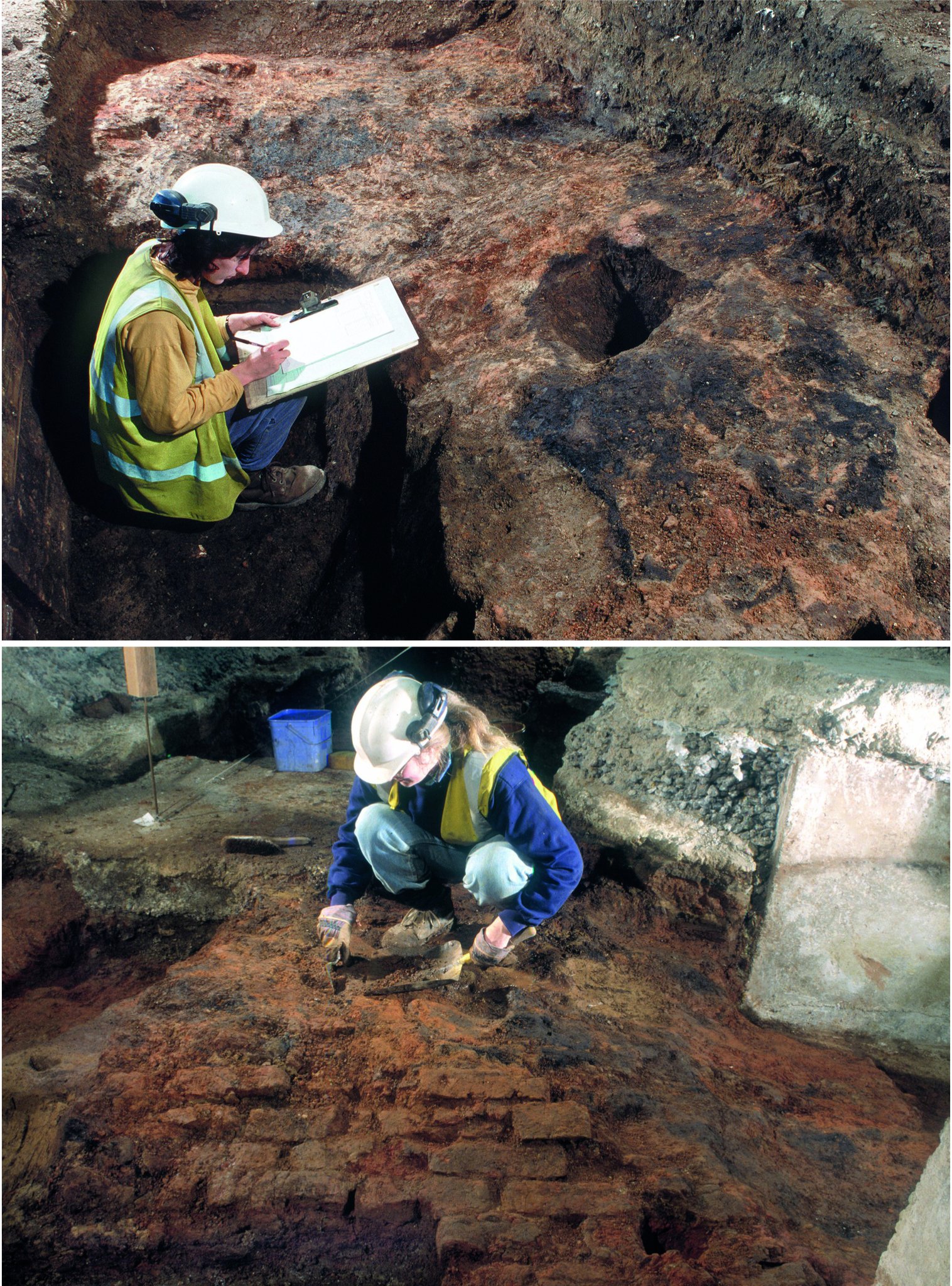

In a trench under modern London, archaeologists hit a line of charcoal and smashed pottery. Above it, Roman streets and later medieval foundations. Below it, an older town. That charcoal band has a name that sounds like a sci‑fi novel: the Boudican Destruction Horizon.

It is the physical scar of a revolt that almost broke Roman Britain. Around 60 or 61 CE, after Queen Boudica of the Iceni was flogged and her daughters raped by Roman soldiers, she led a coalition of tribes that wiped out three Roman towns. Camulodunum (Colchester), Londinium (London), and Verulamium (St Albans) were burned so hard that their remains are still a black line in the soil.

Boudica’s revolt was crushed by the governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus at a battle somewhere along Watling Street. Rome kept Britain. But the question keeps nagging at people reading about that scorch layer: what if she had won?

To answer that, you need to know what actually happened, what Boudica could realistically have achieved, and how Rome usually handled disasters. Then you can test a few grounded scenarios against the hard limits of ancient logistics and politics.

Why Boudica rebelled and how close she came to breaking Britain

Boudica was not a random rebel. She was the widow of Prasutagus, king of the Iceni in eastern Britain. He had ruled as a client king under Rome after the conquest begun by Emperor Claudius in 43 CE. When he died, probably around 60 CE, he tried to split the difference: he left his kingdom jointly to his two daughters and to the emperor in his will.

Roman officials ignored that compromise. According to Tacitus, the imperial procurator Catus Decianus treated the will as an excuse to seize everything. Iceni nobles were stripped of property. Boudica was flogged. Her daughters were raped. That was not just cruelty. It was a political blunder that turned a loyal client kingdom into the core of a rebellion.

At the same time, Roman veterans in the colony at Camulodunum were behaving like occupiers, grabbing land and abusing locals. A temple to the dead emperor Claudius loomed over the town as a symbol of Roman rule and tax burdens. Resentment had been building for years.

When Boudica rose, she was not alone. The Trinovantes joined her, and probably other tribes too. Ancient sources claim she fielded 100,000 or more warriors. Those numbers are inflated, but she clearly had a huge force by British standards. The Roman governor Suetonius had perhaps 10,000 men in Britain, mostly the XIV Gemina legion, parts of XX Valeria Victrix, and auxiliaries. One entire legion, IX Hispana, marched to relieve Camulodunum and was mauled so badly that its infantry were wiped out.

Boudica’s army destroyed Camulodunum, then moved on Londinium. Suetonius decided he could not defend the town with what he had, evacuated who he could, and abandoned it. Boudica burned it to the ground. The same fate hit Verulamium. Ancient writers talk about tens of thousands of Roman civilians and local allies killed. The exact numbers are unknowable, but the destruction was real enough to leave that black horizon under London.

Then Suetonius turned and fought. Somewhere along Watling Street, probably in the Midlands, he chose a tight position with woods behind him and open ground in front. His heavily armed legionaries formed a narrow front. The Britons, confident after three easy victories, attacked in a mass. Roman discipline, armor, and tactics shredded them. Tacitus claims 80,000 Britons died for 400 Romans. The numbers are propaganda, but the scale of the defeat was decisive. Boudica either took poison or died soon after. The revolt collapsed.

So what? Because that battle was the hinge. Flip its result and you do not magically get a free British kingdom, but you do open a range of plausible alternate paths for Roman Britain.

Scenario 1: Boudica wins at Watling Street and Rome abandons Britain

The cleanest fantasy is simple: Boudica wins, Rome cuts its losses, and Britain slips out of the empire in 61 CE. Could that have happened?

First, what would a Boudican victory look like in practical terms? Suetonius had maybe 10,000 disciplined troops. If his army is destroyed, you have:

• The XIV Gemina legion gutted or annihilated.

• Large parts of XX Valeria Victrix lost.

• Auxiliary cohorts scattered or dead.

• One legion (II Augusta) intact in the southwest, but its commander had already failed to join Suetonius in reality.

Roman forts across Britain would suddenly be isolated. Small garrisons could be picked off. The colony at Camulodunum was already gone. Londinium and Verulamium were ash. Local tribes on the fence would see which way the wind was blowing.

Logistically, Britain was a headache. Supplying legions across the Channel meant ships, ports, and cooperation from Gaul. The province had not yet become the rich tax cow it would be later, with its lead, tin, and grain exports. From the Senate’s point of view, Britain was a prestige project of Claudius that had already cost a lot of money and men.

So could Nero have said: enough, pull out?

History gives us a clue. Rome almost never abandoned hard-won provinces in the first century. They had taken years to conquer Britain. Claudius had paraded elephants and British captives in Rome to celebrate it. To walk away less than twenty years later would have been an admission of failure that cut directly against Roman political culture.

Even in disasters like the Teutoburg Forest in 9 CE, when three legions were wiped out in Germany, Rome did not abandon all ambitions out of fear. They pulled back to more defensible lines along the Rhine, but they kept armies in the region and kept raiding. In Judea, after the revolt of 66–73 CE, they poured in more troops until Jerusalem fell.

The only way Rome abandons Britain in 61 is if several pressures line up: a catastrophic defeat, political chaos in Rome, and a lack of spare legions. Nero did face instability later in his reign, but in 61 he was still relatively secure. There were legions in Gaul and Germany that could be reassigned if the emperor cared enough.

So what? A total Roman withdrawal in 61 is possible in theory, but it runs hard against Roman pride and habit. It is the least likely of the big what‑ifs, because it demands a Rome that behaves unlike Rome.

Scenario 2: Boudica forces a negotiated autonomy inside the empire

A more grounded scenario is not “Rome leaves,” but “Rome blinks.” Boudica wins at Watling Street, kills or drives off Suetonius, and Britain becomes a bleeding ulcer. What then?

Start with the military math. After a Roman defeat, Boudica’s coalition would control most of lowland Britain. Roman forts would be under siege or abandoned. The II Augusta legion in the southwest might hold its ground around Exeter and Gloucester, but it would be isolated. Roman commanders in Gaul would be staring at reports of three burned towns, a destroyed army, and a hostile island across the Channel.

Sending one fresh legion might not be enough. They would need at least two or three, plus auxiliaries, to reconquer the province. That means stripping troops from the Rhine or Danube frontiers, which were always tense. Every legion moved to Britain made Gaul or Germany more vulnerable.

Now add politics. Nero liked victories, not quagmires. If his advisors told him that Britain could be pacified only with huge expense and risk, he might look for a face‑saving compromise. Rome had a tool for that: client kingship.

Before full annexation, Rome often ruled through local kings who paid tribute, supplied troops, and followed Roman foreign policy. Herod the Great in Judea is the classic example. In Britain itself, Prasutagus had been one of those client kings.

Imagine Nero’s advisors proposing this: recognize a confederation of British tribes under Boudica or a successor, in exchange for tribute and a promise not to raid Gaul. Keep a small Roman enclave in the southeast around the best harbors. Declare victory in Rome by spinning it as “restoring order and friendship with our British allies.”

Would Boudica accept? Her revolt was triggered by abuse and annexation, not by a philosophical hatred of Rome. Many British elites liked Roman trade goods and status. A deal that restored autonomy, punished the worst Roman officials, and let them keep Roman imports might appeal to some tribal leaders.

The sticking point is ideology. Roman writers frame Boudica as a freedom fighter, but she was also a queen in a world of aristocratic politics. A negotiated autonomy that left a token Roman presence might look like victory to her, especially if it came with formal recognition of her rule.

If that happens, Britain becomes a semi‑independent client region again. Romanization slows. There is no full grid of Roman roads, fewer stone towns, probably no Hadrian’s Wall a few decades later. Latin spreads less. Christianity, which later used Roman roads and cities as its arteries, might arrive later or in different forms.

So what? A negotiated autonomy is plausible because it fits Roman habits: keep face, keep trade, accept indirect control when direct rule is too expensive. It would have turned Britain into a semi‑Roman fringe instead of a fully integrated province.

Scenario 3: Boudica wins the battle, Rome wins the war

The third scenario is the most Roman of all: Boudica wins at Watling Street, but it only delays Roman rule by a few years and makes the reconquest nastier.

Look again at Teutoburg. Three legions vanished in the German forests. Augustus is said to have walked the palace crying, “Quinctilius Varus, give me back my legions.” Yet Rome did not swear off Germany forever. They reinforced the Rhine, punished some tribes, and adjusted their ambitions. The empire absorbed the shock.

In Britain, a Boudican victory would be a shock of similar scale. The response would likely be:

• Suetonius recalled or killed in battle. A new governor appointed, probably a hardliner with a reputation for toughness.

• Two or three legions shipped from Gaul or Germany, raising the British garrison to 4–5 legions temporarily.

• A massive punitive campaign, targeting not just warriors but the economic base of rebellious tribes: fields, herds, and settlements.

Rome had the shipping to move legions across the Channel. They had ports at Gesoriacum (Boulogne) and other Channel harbors. Britain’s geography made it hard for tribes to unite across long distances. Tribal politics were fractious. Boudica had managed to build a coalition once, but keeping it together under pressure from a reinforced Roman army would be hard.

After a year or two of brutal campaigning, Rome could re‑establish control over the southeast and midlands. Some tribes would cut deals. Others would be crushed. Boudica herself might die in battle or be captured and paraded in Rome, like Vercingetorix of the Gauls a century earlier.

The long‑term effect would be a harsher Roman Britain. In our timeline, after the revolt, Nero’s advisors actually toned down some abuses. The harsh procurator Catus Decianus was replaced. Tax policy was softened to avoid another explosion.

In this alternate line, a bigger Roman defeat might produce the opposite: more forts, more direct rule, more confiscated land for veterans. The Iceni and Trinovantes could lose their elites and be more thoroughly colonized. The temple of Claudius at Camulodunum might be rebuilt as a triumphal symbol over the “rebels.”

Roman Britain might look more like a classic conquest zone, with a thicker military presence and less tolerance for local autonomy. The end result by, say, 120 CE might still be a province with towns, baths, and Latin inscriptions. It just gets there through more blood.

So what? This scenario keeps the broad arc of history intact. Britain ends up Roman, but the road is rougher and the memory of Boudica’s victory becomes a cautionary tale inside the empire rather than a national legend outside it.

Which Boudica scenario is most plausible, and what would it change?

Weighing these three options, the most plausible is Scenario 3: Boudica wins a major battle, Rome absorbs the loss, and reconquers Britain with extra force. Scenario 2, negotiated autonomy, is possible but needs a Nero more cautious than the one we know. Scenario 1, total withdrawal, demands a Rome that behaves out of character for the first century.

Why is Scenario 3 strongest? Because it matches Roman patterns:

• Rome hated to abandon conquests that were tied to an emperor’s prestige.

• The empire had enough legions nearby to reinforce Britain if it chose to.

• After big revolts, Rome usually doubled down, then adjusted policy, not walked away.

In that world, the Boudican Destruction Horizon under London might be thicker, with a second layer from later fighting. Archaeologists might find more emergency hoards of coins and valuables buried by people who never came back. Inscriptions might mention a “second conquest” of Britain under a different emperor.

Scenario 2, a semi‑independent Britain, would have had deeper cultural effects. No long Roman occupation means:

• Fewer Roman roads and towns, so later Anglo‑Saxon and Viking movements look different.

• Latin less embedded in British elites, which might change the later development of English and Welsh.

• Christianity arriving later or via Ireland and the north, not through Romanized southeastern towns.

But that requires Rome to accept a client kingdom in a place where it had already planted colonies and legions. Once Rome had invested that much concrete and blood, it usually preferred to keep direct control.

As for Scenario 1, a complete Roman exit in 61 would have turned Britain into a patchwork of tribal kingdoms with intermittent contact with the continent. There would be no Hadrian’s Wall, no Roman York, no Bath with its temple and baths. Later invasions from Saxons or Vikings would be hitting a very different political map. Yet the odds of Nero swallowing that humiliation are slim.

So what? The most likely alternate Boudica is not a queen who drives Rome into the sea, but a rebel whose one big battlefield win makes Roman Britain harsher in the short term and more militarized in the long term. The black scorch layer under London would still be there. It would just be part of a longer, nastier story of conquest.

That is why that thin band of charcoal matters. It is not just evidence of one revolt. It is a reminder of how close empires can come to losing their grip, and how much has to shift before they actually let go.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Boudica and why did she revolt against Rome?

Boudica was queen of the Iceni tribe in eastern Britain in the first century CE. After her husband Prasutagus, a client king of Rome, died, Roman officials ignored his will, seized Iceni property, flogged Boudica, and raped her daughters. Combined with long‑standing resentment against Roman land seizures and taxes, this triggered a large tribal revolt around 60–61 CE.

What cities did Boudica destroy and what is the Boudican Destruction Horizon?

Boudica’s forces attacked and destroyed three major Roman towns: Camulodunum (Colchester), Londinium (London), and Verulamium (St Albans). They burned them so completely that archaeologists today find a distinct layer of ash, charcoal, and debris in the soil. In London this layer is called the Boudican Destruction Horizon, a physical record of the revolt under modern buildings.

Could Boudica realistically have driven the Romans out of Britain?

It was possible but unlikely. Even if Boudica had won the key battle against the governor Suetonius, Rome had other legions in Gaul and Germany that could be sent to reconquer Britain. Roman political culture made abandoning a recently conquered province very rare. A more plausible outcome is that a Boudican victory would have forced Rome into a harsher reconquest or a temporary compromise, not a permanent withdrawal.

How would history change if Boudica had defeated the Romans?

If Boudica had defeated Suetonius, the short‑term effects would likely include more destruction in Roman Britain and a larger Roman military response. In the most plausible scenario, Rome would eventually reconquer the province with extra legions, making early Roman Britain more militarized and brutal. In less likely scenarios where Rome accepted a client kingdom or withdrew, Britain would have been less Romanized, which could have altered later patterns of language, Christianity, and political development.