Bill Murray had one condition. He would do Wes Anderson’s second feature, Rushmore, for the same pay as an unknown 18‑year‑old kid named Jason Schwartzman. But he wanted to be able to leave for a golf tournament.

Anderson said yes. That odd little bargain on a modest 1998 production became the seed of one of the strangest pay practices in Hollywood: a flat-fee system where, on some Wes Anderson films, the actors all get the same rate.

Wes Anderson’s flat-fee salary system is a way of paying cast members where everyone, from Oscar winners to first-timers, receives essentially the same base pay for a project. It is not how Hollywood usually works, and that is exactly why people keep asking about it.

To understand what this system is, why it started, and what it changes, you have to look at a director who built his own little film universe and then tried to bend the money rules to match it.

What is Wes Anderson’s flat-fee salary system?

In a standard Hollywood movie, actors are paid on a sliding scale. Big stars command millions plus back-end profit participation. Supporting actors get less. Day players get scale. The pay structure mirrors a hierarchy of fame and box office power.

Wes Anderson, especially from the late 1990s onward, has often flipped that logic. On several of his projects, he has used a flat-fee or near-flat-fee system. Everyone in the ensemble, no matter how famous, gets roughly the same base salary for the shoot.

In practice, this usually means a relatively modest paycheck by Hollywood standards. The exact numbers are not public, and they likely vary from film to film. But multiple actors and producers have described a consistent pattern: Anderson offers a fixed fee, often lower than the actor’s usual quote, with little or no back-end participation. You either sign on for that amount or you do not do the movie.

Wes Anderson’s flat-fee system is a pay structure where actors agree to work for the same limited rate, trading big salaries for the chance to be part of his films. It is less a union rule than a gentleman’s agreement: same money, same conditions, same project.

So what? Because pay is power in Hollywood, a flat-fee system quietly rewrites who holds that power on a Wes Anderson set and what kind of people are willing to show up there.

What set it off: Rushmore, Bill Murray, and a tiny budget

The origin story usually begins with Rushmore, Anderson’s 1998 film about an eccentric prep school kid. Anderson had made one feature before, Bottle Rocket, which had not set the box office on fire. He was not yet the guy who could call up half of Hollywood and fill a cast list in a weekend.

What he did have was a script, a producer in James L. Brooks backing him, and a young, unknown lead: Jason Schwartzman, a teenager from a musical family with zero film credits. What he did not have was a huge budget. Rushmore was a mid-range studio gamble, not a blockbuster.

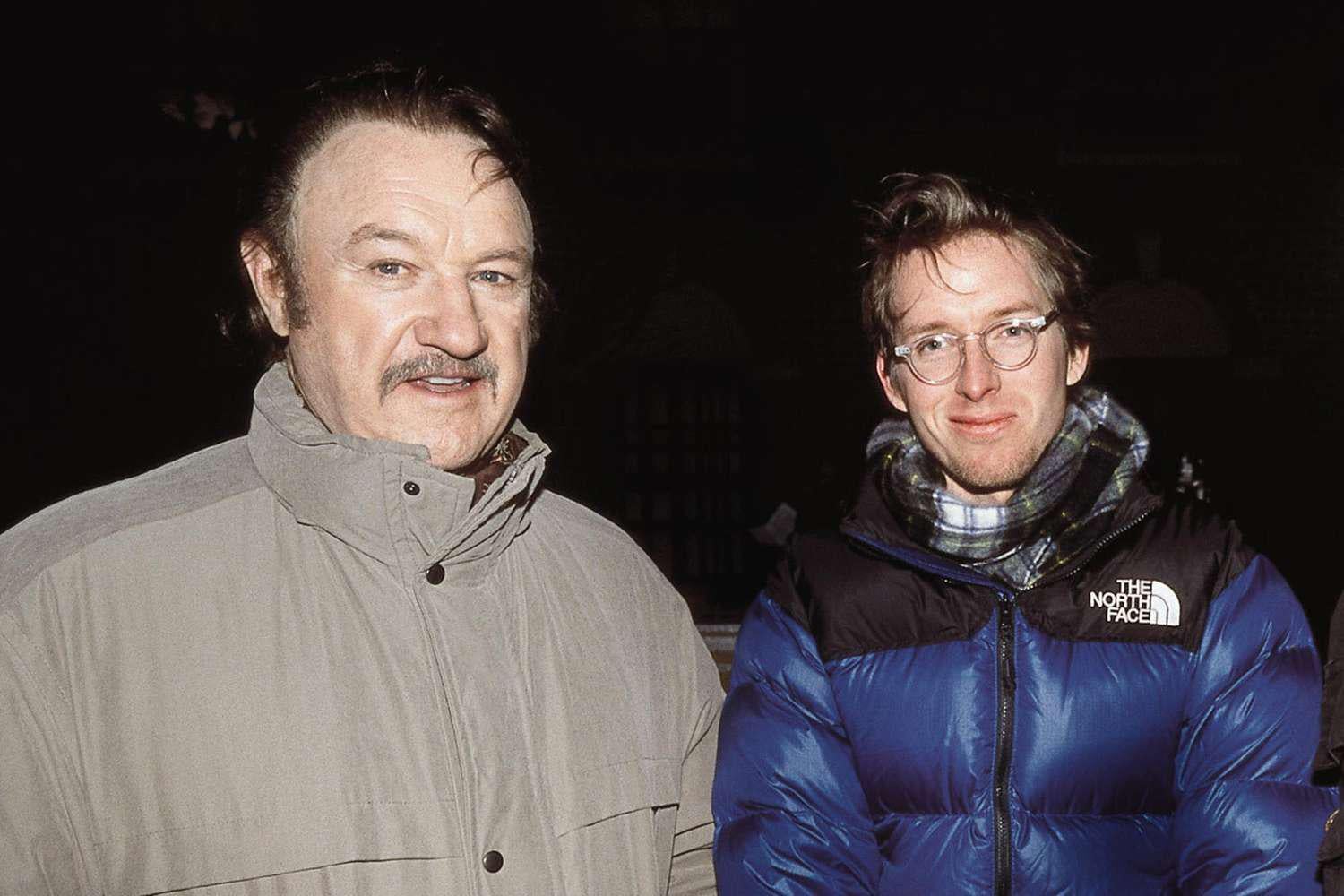

Enter Bill Murray. By the late 1990s, Murray was a comedy legend. Ghostbusters, Groundhog Day, Caddyshack. He could command serious money. When he agreed to play Herman Blume, the weary industrialist who befriends Schwartzman’s character, it changed the film’s prospects overnight.

According to Anderson and others who have told the story over the years, Murray made an unusual offer. He would take the same pay as Schwartzman, the unknown teenager, as long as he had the freedom to duck out for a golf tournament. The golf part is the joke. The equal pay part is the point.

On a small movie, that gesture mattered. Murray was effectively saying: I am not here for the paycheck. I am here for the work. Treat me like the kid. The studio got a star at a price they could afford. Anderson got a collaborator who was signaling that the usual hierarchy did not apply.

That decision on Rushmore did not instantly create a formal “flat-fee system,” but it set a pattern. It showed Anderson that big names would sometimes take small money if they believed in the project. It also showed him that pay could be a tool to create a certain kind of set: less about status, more about the film.

So what? Because Rushmore proved that a major star would voluntarily flatten the pay scale, it opened the door for Anderson to keep asking future stars to do the same thing.

The turning point: from one-off deal to a house rule

After Rushmore, Anderson’s career climbed. The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) brought him Oscar attention. The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004) was bigger, weirder, and more expensive. The casts grew more crowded with names: Gene Hackman, Anjelica Huston, Gwyneth Paltrow, Ben Stiller, Cate Blanchett, Willem Dafoe, Jeff Goldblum.

At this point, Anderson could have gone the standard route. Pay the biggest stars millions. Fill in the rest with cheaper talent. Let agents fight it out. Instead, he began to treat the Rushmore experiment as a template. On ensemble films, he offered a single rate or a narrow band of rates and expected everyone to accept that this was not a payday job.

By the time he was making movies like The Darjeeling Limited (2007), Moonrise Kingdom (2012), and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014), the pattern was clear from interviews and industry chatter. Actors were taking far less than their usual quotes to be in a Wes Anderson film. Some described it as “scale plus” or “indie money.” Some said flatly that everyone got the same fee.

Anderson himself has talked about this in broad terms. His films, he has said, are not built around giant salaries. The money goes into the production: the sets, the locations, the carefully controlled color palettes, the stop-motion animation, the long rehearsal periods. If you want to be part of that world, you accept that the pay is modest.

There is no public contract that says “all actors shall be paid identically.” Reality is messier. A-list stars sometimes still get a bit more. Cameos may be paid differently from leads. But the core idea hardened into a house rule: on a Wes Anderson movie, the pay scale is flatter and lower than the Hollywood norm, and everyone knows it going in.

So what? Because once this became an expectation, it turned Wes Anderson films into a separate economic zone inside Hollywood, with its own unwritten rules and its own type of participant.

Who drove it: Wes Anderson, Bill Murray, and a loyal troupe

Wes Anderson is the architect of the system, but he did not build it alone. It took a certain kind of actor to make it viable.

Bill Murray is the obvious first driver. His choice on Rushmore sent a signal to other stars: you can afford to take a pay cut for something interesting. Murray kept coming back for Anderson projects, often in supporting roles that would not pay anywhere near his market rate. His presence gave Anderson credibility and continuity.

Then there is Jason Schwartzman, the teenager from Rushmore who grew into one of Anderson’s regulars. Schwartzman’s early equal-pay situation with Murray became part of the lore. He returned for The Darjeeling Limited, Fantastic Mr. Fox, Moonrise Kingdom, and others, often as part of a crowded ensemble. He was a living reminder that this world did not revolve around one star’s paycheck.

Other repeat players joined the troupe: Owen Wilson, Luke Wilson, Anjelica Huston, Willem Dafoe, Tilda Swinton, Adrien Brody, Jeff Goldblum, Frances McDormand, Edward Norton, Ralph Fiennes, Saoirse Ronan. Many of them are Oscar winners or nominees. Their agents could, in theory, demand much more elsewhere.

When they show up in a Wes Anderson film, they are making a different calculation. They get artistic cachet, a distinctive credit on their filmography, often a fun role, and the chance to be part of a recurring creative community. They give up the big check.

Anderson’s own working style feeds this. He is known for long rehearsals, precise direction, and a tight-knit crew. The films feel like theater companies or summer stock troupes. The flat-fee system fits that vibe. You are not a “guest star.” You are part of the company for this run.

So what? Because without a core group of actors willing to trade money for creative satisfaction, Anderson’s pay experiment would have collapsed. Their choices made the system real instead of just theoretical.

What it changed: power, access, and the myth of equal pay

On paper, “everyone gets the same rate” sounds like a utopian fix for Hollywood’s pay gaps. In practice, Wes Anderson’s system is more complicated and more limited than that.

First, the obvious change: it flattens some of the power imbalance on set. When you know that the Oscar winner next to you is making roughly what you are, it chips away at the sense that one person is the sun and everyone else is orbiting. That can make collaboration easier and egos a bit smaller.

Second, it changes who can afford to be there. A flat, modest fee is not a problem for someone who has already made millions or who has other income streams. It can be a problem for actors who are still scrambling to pay rent or support families. Equal rates do not mean equal impact.

So the system is egalitarian in one sense and selective in another. It favors people who can afford to treat a Wes Anderson film as a prestige project rather than a financial lifeline. That can skew casts toward the already successful or those with safety nets.

Third, it affects the budget itself. Money that might have gone into a few giant salaries can be spread across production design, costumes, stop-motion animation, or the ability to shoot on location. When you watch The Grand Budapest Hotel or The French Dispatch, you are seeing where some of that reallocated money went: into the frame instead of into a single paycheck.

Finally, it challenges the standard Hollywood myth that “you are worth what you can negotiate.” On an Anderson film, you are worth what the project can afford and what the director decides is fair. That is a different kind of value system, one that puts the film’s needs above the market’s usual logic.

So what? Because by flattening pay on his own projects, Anderson has created a small but visible counterexample to Hollywood’s star-driven salary model, and that keeps the broader debate about fairness and value alive.

Why it still matters: pay, prestige, and how we value art

Wes Anderson’s flat-fee system is not going to replace Hollywood’s normal way of doing business. Most big films still pay stars huge sums and tie their compensation to box office results. Agents still fight for every dollar. Studios still believe that certain names are worth certain numbers.

But his approach matters for a few reasons.

First, it shows that big names will sometimes work for far less if they trust the director and care about the project. That weakens the idea that the market is some immovable force. It is, at least partly, a set of choices.

Second, it feeds into current conversations about pay transparency and equity. When people hear that “everyone on a Wes Anderson film gets the same rate,” they often assume it is a universal rule or a perfect fix. It is neither. It is a specific solution in a specific context. That nuance is useful when people talk about equal pay in other industries.

Third, it reframes what a “prestige project” is. For decades, actors have taken pay cuts to do theater, indie films, or passion projects. Anderson’s films sit in a strange middle ground: not micro-budget indies, not massive blockbusters. His flat-fee system formalizes the idea that these mid-budget, auteur-driven films are about something other than cash.

And finally, it reminds audiences that the economics behind a movie shape what ends up on screen. When you watch a Wes Anderson film packed with famous faces, it is easy to assume the studio just opened a vault. In reality, many of those people chose to be there for less money than they could have made elsewhere.

So what? Because every time someone hears that Bill Murray once took the same pay as an unknown teenager to make Rushmore, it nudges the conversation about how we value work, fame, and art, both inside Hollywood and outside it.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does Wes Anderson really pay all his actors the same?

On several of Wes Anderson’s films, he has used a flat-fee or near-flat-fee system where actors are offered roughly the same modest rate. The exact numbers and whether they are perfectly identical are not public, and there can be some variation, but multiple actors and producers have described his casts as being paid on a much flatter scale than normal Hollywood productions.

How did Wes Anderson’s flat-fee salary system start?

The story usually traces back to his 1998 film Rushmore. Bill Murray agreed to act in the film for the same pay as 18-year-old first-time actor Jason Schwartzman, reportedly on the condition that he could leave for a golf tournament. That choice showed Anderson that major stars would sometimes accept equal, lower pay for a project they believed in, and he carried that idea into later ensemble films.

Why would big stars take less money to work with Wes Anderson?

Actors often accept lower pay on Wes Anderson films because they value the creative experience, the distinctive style, and the prestige of being in his work. Many of his regular collaborators already earn high salaries on other projects, so they can afford to treat an Anderson film as a passion project rather than a primary income source. They trade money for artistic satisfaction and association with a respected director.

Is Wes Anderson’s equal pay system fair to lesser-known actors?

It depends on how you define fair. A flat-fee system can reduce status differences on set, since everyone is paid about the same. But equal rates do not mean equal impact. A modest fee is easier for a wealthy, established star to absorb than for a struggling actor. So while the system can feel egalitarian, it can also favor those who already have financial security.