Last time on Unsolved Archaeology, we talked about the Moai of Easter Island, the sentries that face the sea and protect Rapa Nui from anything that might come to the island from it. How were they made? What were they for? Were they representative of gods, spirits, or of prominent leaders in the tribe? We explored all of those questions, looking for answers.

This time, we’re talking about the Minoans, a civilization that lived just off of the Peloponnese of Greece. We know a lot about who they were and how they lived. What we don’t know is where they disappeared to.

Who Were the Minoans?

The Minoans were a trade-based, nautical civilization that predated Ancient Greece. Some scholars have called them the “first link in the European chain”. Their influence stretched all across the ancient world, from Egypt to Cyprus, Canaan, and Anatolia (Turkey). They lived on the island of Crete, south of the Greek Peloponnese.

![The palace of Knossos [PHOTO: wikimedia]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/1024px-Knossos_-_North_Portico_02-300x225.jpg)

Something happened to them in 1700 BC… perhaps an earthquake or an invasion. The palaces were all destroyed, but the island quickly recovered.

Minoan handcrafted items have been found all over the Greek mainland. Minoan ceramics have been found in Egyptian cities, and it’s widely thought that Egyptian hieroglyphics were the inspiration for Minoan pictographic writing.

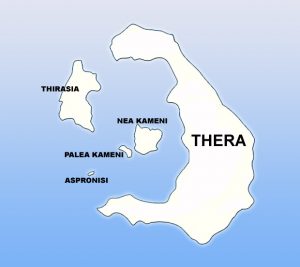

When 1450 BC hit, so did another catastrophe, one that would be instrumental in shaping the Minoan civilization. It was likely another earthquake or an eruption of a nearby volcano at Thera. Either way, all of the the palaces were destroyed. All of them, that is, expect the one at Knossos. The nobles at Knossos quickly took advantage of the situation and established a dynasty of rulers that would dominate Crete in the years to come.

Minoan Culture

The Minoans were an unique, sophisticated culture of a kind that the ancient world had not yet seen. They were based around trade, rather than any sort of production or agriculture, and from 1700 BC onwards, they were extremely organized.

They traded in saffron: a spice that could be compared in value to frankincense or, later, pepper. They also traded in ceramics, copper and tin working, and intricately-worked gold and silver jewelry.

Their cities were connected with stone-paved roads, roads that had intricate drainage systems. Running water was provided to the upper class through a system of clay pipes. They had their own unique architecture style. The palaces were decorated with intricate, beautiful mosaics, frescoes, and stone carvings.

Their culture may have been matriarchal– a rarity in the ancient world. Their religion was focused on female deities, including the famous “Snake Goddess”. The goddesses vastly outnumbered the male gods. Their religion was a sophisticated one, addressing gender identity, rites of passage, and death.

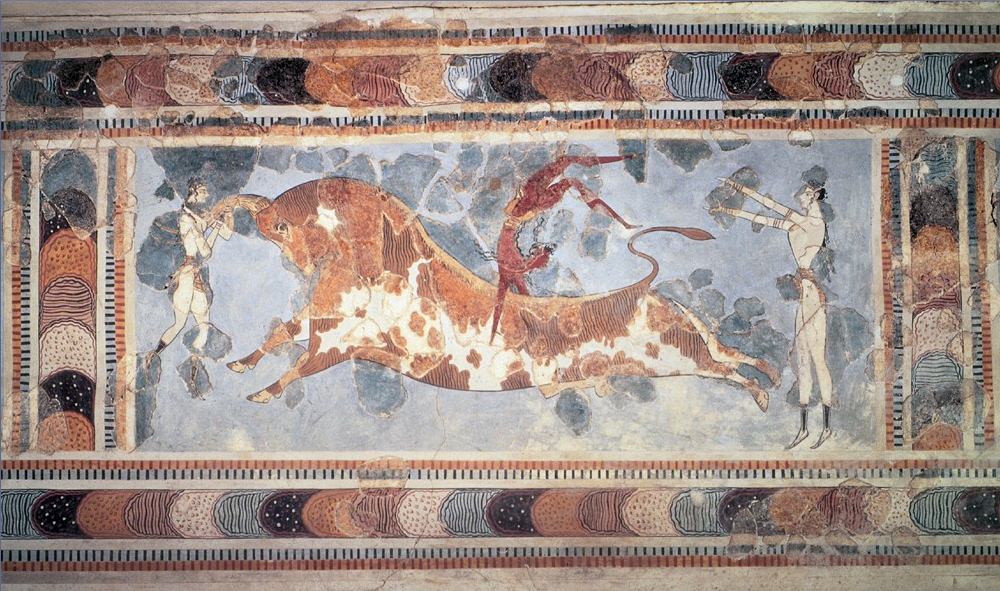

The Minoans also had a habit of leaping over the backs of bulls for fun. No-one knows exactly why this sport existed. Bulls did have religious significance in ancient Minoan culture, and there’s evidence that this sport was part of important festivals and rituals, but its exact purpose is unclear.

The Phaistos Disk

One of the most mysterious and enigmatic artifacts found on Crete is called the Phaistos Disk. It’s the best-preserved artifact we have containing the written language of the Minoans. It’s a disk made of fired clay that was found in the palace of Phaistos, dating to the middle or late Bronze Age on Crete. It’s engraved with 241 symbols that comprise 61 words. 31 are on side A, and 30 are on side B.

Many archaeologists and linguists have attempted to crack it in order to hopefully gain further understanding of the Minoan civilization, but so far, no real progress has been made. Some think that the disk catalogs prayers, others an adventure story, others a board game or a geometric theorem. None of these theories have been proven. The disk remains a mystery.

Where Did They Go?

Crete lived in a culture of perpetual peace. There has been no archaeological evidence for a Minoan army, and any depictions of battles or violence on the palace walls seem to be merely part of blood sport or ritual. The cities were not well fortified. Perhaps they felt completely secure on an island set apart from the rest of the warmongering world around them.

Curiously, all evidence of this complex, powerful, trade-based civilization just disappears around 1200 BC. The Minoans simply fell off the map. What happened to them? Where did they go?

Greek archaeologist Spyridon Marinatos proposed a theory in 1935. Crete was no stranger to natural disaster. It was 100 kilometers away from the active volcano of Thera. Around the later period of the civilization, Thera exploded. It was the largest explosion known to the civilization, and covered Crete in a layer of pumice. It’s widely thought that this severely affected Crete. Perhaps the ashfall killed all the plant life and plunged the population into starvation. Some archaeologists believe the explosion triggered a massive tsunami that devastated the island.

However, archaeologists have found evidence of the Minoan culture on Crete after the date of the Thera eruption. The eruption may have weakened the empire, but it did not destroy it.

Another theory has arisen though. Across the ocean from Crete, there was another civilization on the mainland of Greece: the warlike Mycenaeans. Perhaps, when Crete fell into decline after the natural disaster of the Thera eruption, the Myceneans saw their chance and invaded.

There’s also evidence that the Minoan civilization had begun to eat themselves out of house and home. Crete simply couldn’t sustain the population past a certain point.

So, which is it? An eruption? An earthquake? A tsunami? Invasion from the mainland? Starvation? Perhaps it was all of them. Perhaps it was none of them. Nobody really knows the real reason why the Minoan civilization disappeared after 1200 BC. We can make educated guesses, but, perhaps no one will ever really know. It’s a mystery that continues to fascinate archaeologists and historians to this day.