They heard the boots before they saw the uniforms.

On an autumn day in 1943, German soldiers marched into Fatebenefratelli Hospital on Tiber Island in Rome. They were hunting Jews. Inside, patients lay in beds marked with a strange diagnosis: “Morbo di K” or “Syndrome K.” The men in white coats warned the soldiers not to get too close. The disease was said to be contagious, horrible, and fatal.

Terrified of infection, the Nazis backed away. The patients coughed theatrically. The soldiers fled the ward.

Syndrome K was not real. It was an invented illness, dreamed up by a small group of Italian doctors to hide Jewish men, women, and children from deportation. During the Nazi occupation of Rome, they used medical charts, fake diagnoses, and their own reputations to turn a hospital into a refuge.

Syndrome K was a fake disease created in 1943 at Fatebenefratelli Hospital in Rome to disguise Jewish refugees as dangerously ill patients. It allowed doctors to protect them from Nazi roundups by exploiting the occupiers’ fear of contagion.

To understand how three doctors and a handful of nurses pulled off this deception, you have to start with the fall of Mussolini, the arrival of the Germans, and a small island in the Tiber that suddenly became one of the most unlikely safe houses in occupied Europe.

Why Rome’s Jews were suddenly in mortal danger in 1943

For most of the Second World War, Rome was under Fascist rule, but not under direct German occupation. Benito Mussolini’s regime had passed anti-Jewish racial laws in 1938. Jews were pushed out of schools, professions, and public life, but mass deportations from Italy did not begin until later in the war.

That changed in 1943. In July, Mussolini was deposed. In September, Italy signed an armistice with the Allies. The German response was swift. Wehrmacht and SS units poured into the Italian peninsula to disarm Italian troops and take control. Rome, suddenly, was a German-occupied city.

For Rome’s Jewish community, one of the oldest in Europe, the danger escalated overnight. In mid-October 1943, the SS carried out a large raid in the Roman Ghetto. Around 1,000 Jews were rounded up in a single day. Most were deported to Auschwitz. Very few survived.

Word of the raid spread fast. Those who escaped went into hiding in convents, monasteries, private apartments, and, in some cases, hospitals. One of those hospitals was Fatebenefratelli, run by the Brothers Hospitallers of Saint John of God, a Catholic order with a long tradition of caring for the sick in Rome.

The German occupation turned Rome into a city of sudden choices: collaborate, keep your head down, or resist. For a few doctors on Tiber Island, resistance began with a diagnosis written in careful handwriting on a medical chart.

So what? The shift from Fascist rule to direct Nazi occupation turned existing prejudice into a machinery of deportation and murder, forcing ordinary Romans, including doctors, to decide whether they would risk their lives to protect their neighbors.

Who invented Syndrome K and what was it supposed to be?

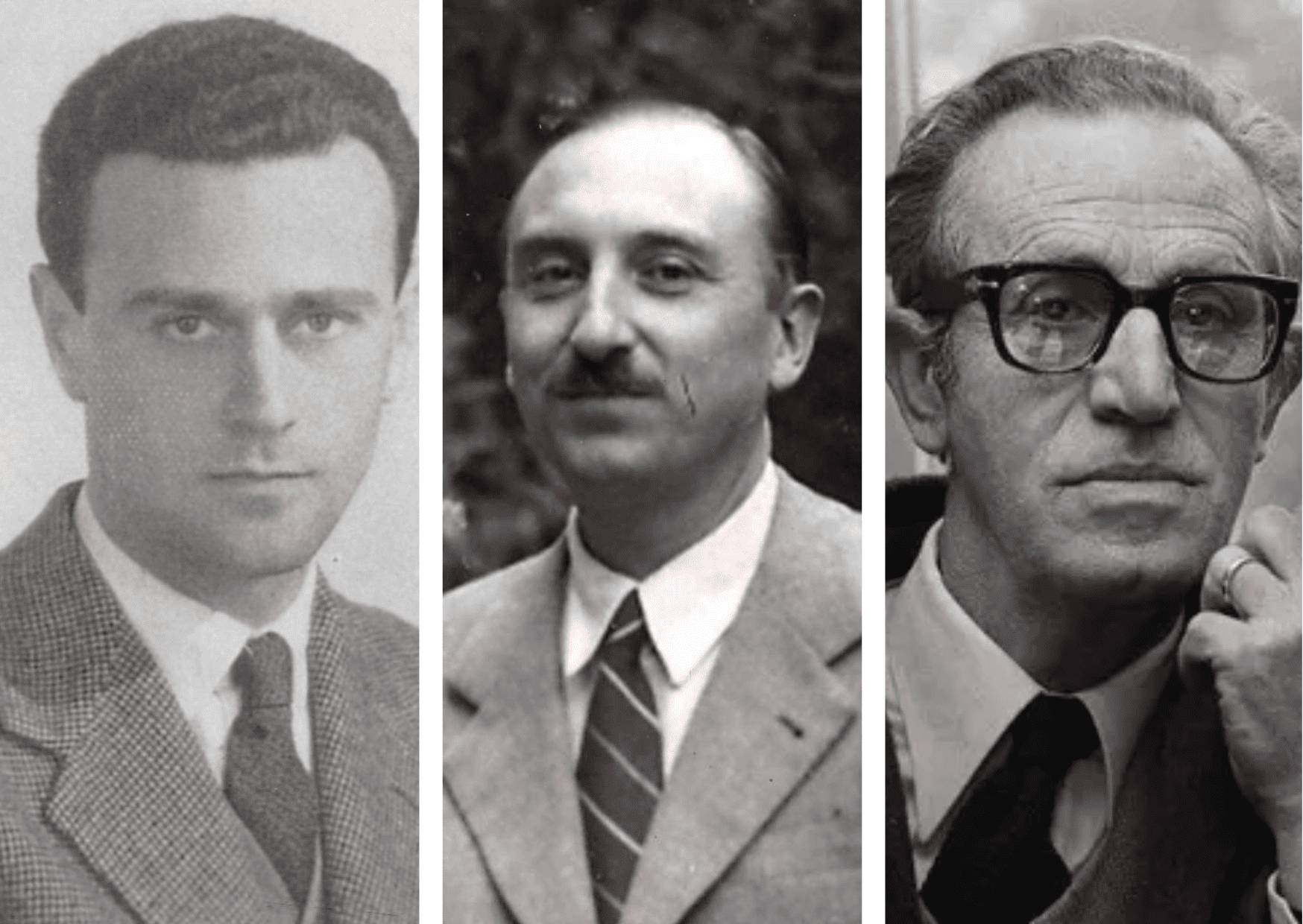

The story of Syndrome K centers on three doctors at Fatebenefratelli: Dr. Giovanni Borromeo, the hospital’s director; Dr. Adriano Ossicini, a young anti-Fascist physician; and Dr. Vittorio Emanuele Sacerdoti, a Jewish doctor working under a false identity.

Borromeo was a respected Roman physician with a quiet streak of defiance. He had already clashed with the Fascist regime and had been pushed out of other posts. At Fatebenefratelli, he had more autonomy and the support of the religious order that ran the hospital.

Ossicini was in his twenties, politically active, and connected to the Resistance. Sacerdoti, a Jew, had been fired from his previous job under the racial laws. Borromeo hired him anyway, hiding him under the name of a non-Jewish colleague. That alone was a risky act.

According to later testimonies, it was within this small circle that the idea of a fake disease took shape. They needed a label that would scare the occupiers away. The diagnosis they came up with was “Sindrome K” or “Morbo di K.”

What did the K stand for? The sources are not entirely consistent. Some later accounts say it was a dark joke aimed at two Nazi officials: Albert Kesselring, the German commander in Italy, and Herbert Kappler, the SS chief in Rome. Others suggest it was simply a random letter that sounded suitably clinical. The doctors themselves, when interviewed decades later, leaned toward the Kesselring/Kappler explanation, but historians note that exact origins are hard to pin down.

Either way, the meaning inside the hospital was clear. On charts and ward lists, “K” meant “this person is Jewish” or “this person is a political fugitive.” It was a code for “protect this patient at all costs.”

Syndrome K was defined as a severe, highly contagious neurological or pulmonary disease, depending on who was asking. The important part was not the medical description but the fear it triggered. The Nazis were wary of typhus, tuberculosis, and other infectious illnesses that could spread among troops. The doctors used that fear as a shield.

So what? Inventing Syndrome K gave the hospital staff a flexible, deniable tool: a way to hide Jews in plain sight under a medical pretext that played directly on the occupiers’ anxieties.

How Fatebenefratelli Hospital turned into a refuge

Fatebenefratelli Hospital sat on Tiber Island, connected to the rest of Rome by two bridges. That geography made it both exposed and oddly self-contained. It was easy to reach, but also easy to control who came and went.

After the October 1943 raid on the Ghetto, Jewish families began arriving at the hospital seeking help. Some came through contacts with the Brothers Hospitallers. Others were directed there by Resistance networks or sympathetic priests. The hospital was already treating regular patients, so any extra bodies had to be explained.

Borromeo and his colleagues admitted these refugees as “patients” suffering from Syndrome K. They were placed in a special ward, often alongside real patients with less dangerous conditions. Nurses and doctors briefed them: if Germans entered, they were to cough, wheeze, and look as sick as possible.

The hospital also used other tricks. Records were altered or kept in duplicate, with one version for internal use and a sanitized version for any outside inspection. Some people were listed under false names. Others were declared dead on paper while still very much alive in a bed upstairs.

One advantage the doctors had was the hospital’s reputation. Fatebenefratelli was known as a serious medical institution. When its staff said a ward contained patients with a dangerous infectious disease, it carried weight. The white coat, in this case, was a kind of armor.

How many people did Syndrome K save? Exact numbers are hard to prove, but survivor testimonies and later research suggest that dozens of Jews passed through the hospital in this way. Some stayed for weeks. Others were hidden for a few days before being moved on to safer hiding places.

So what? By turning their hospital into a disguised safe house, the doctors and brothers at Fatebenefratelli used the normal routines of medicine to carve out a pocket of safety inside an occupied city.

What happened when the Nazis came to inspect Syndrome K?

The most dramatic moments in the Syndrome K story came when German forces entered the hospital itself.

On at least one occasion in late 1943, Nazi soldiers arrived to search for Jews and Resistance members. They had already raided convents and private homes. A hospital on an island was not off-limits.

When word reached the staff that the soldiers were coming, the plan went into effect. Patients in the Syndrome K ward were told to cough loudly, breathe heavily, and avoid eye contact. The doctors warned the soldiers that this particular ward contained people with a dangerous, possibly lethal, contagious disease.

Accounts from doctors and survivors describe the same scene: soldiers approaching the ward, hearing the hacking coughs and seeing the drawn faces, then stopping at the threshold. Not eager to risk infection, they accepted the explanation and turned away, focusing their search on other parts of the building.

There is no evidence that the Nazis ever tried to verify Syndrome K with their own medical staff. In occupied Europe, German authorities did use doctors to inspect hospitals and certify conditions. In Rome, however, the combination of fear, haste, and the hospital’s status appears to have worked in the doctors’ favor.

The danger was real. If the ruse had been exposed, the consequences for the hospital staff and their hidden patients would have been severe. The SS in Rome, under Kappler, did not hesitate to order executions and deportations for far less.

Yet the deception held. The Syndrome K ward was never emptied by force. The patients who faked their symptoms survived those inspections.

So what? The successful bluff during Nazi inspections proved that a carefully crafted lie, backed by professional authority and collective discipline, could outwit a brutal occupation machine that was not as all-seeing as it liked to appear.

How the hospital staff balanced medicine, ethics, and resistance

From the outside, Syndrome K might sound like a clever prank. Inside the hospital, it was a daily moral and practical balancing act.

Doctors swear to treat the sick and to tell the truth to their patients. Here, they were lying to the occupiers and, in some ways, to their own medical records. They were also taking on extra “patients” who were not medically ill, which could divert resources from those who were.

Borromeo and his colleagues saw it differently. For them, the Jews and fugitives in their care were sick in the only way that mattered in 1943 Rome: they were marked for death by the state. The hospital’s duty, as they understood it, was to preserve life. If that required fake diagnoses and altered charts, so be it.

The Brothers Hospitallers, as a Catholic order, faced their own risks. The Vatican’s position during the Holocaust was cautious and often ambiguous, but many individual priests and religious communities in Rome chose to hide Jews in defiance of German orders. Fatebenefratelli fit into that broader pattern of quiet, local resistance.

There were practical challenges too. Extra mouths to feed in a time of shortages. The constant fear of informers. The need to coordinate with Resistance groups who might move people in and out of the hospital at odd hours.

Yet the staff kept the operation going for months. They did so without public recognition, and with no guarantee that anyone would remember what they had done if they were caught and killed.

So what? The daily running of Syndrome K shows how resistance in wartime often looked less like dramatic sabotage and more like a string of small, risky decisions made by people who chose to bend their professional roles toward saving lives.

What happened after Rome’s liberation and how the story came out

Rome was liberated by Allied forces in June 1944. The German occupiers withdrew north. The immediate danger to the city’s Jews and to those who had sheltered them receded.

After the war, the story of Syndrome K did not instantly become famous. Like many acts of local rescue, it lived first in survivor memories, hospital lore, and occasional interviews. The doctors went back to their careers. The hospital continued its work.

Over time, historians and Holocaust researchers began to piece together what had happened on Tiber Island. Testimonies from survivors who had been hidden in the hospital, along with statements from Borromeo, Ossicini, and Sacerdoti, gave substance to the story. Hospital archives and wartime documents helped confirm that Fatebenefratelli had indeed sheltered Jews and Resistance members.

In 2004, Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust remembrance authority, recognized Giovanni Borromeo as Righteous Among the Nations, an honor given to non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. The citation mentioned his role in hiding Jews at Fatebenefratelli, including through the invention of a fictitious disease.

Ossicini, who lived to an advanced age, gave several interviews in which he described Syndrome K and the hospital’s wartime activities. Sacerdoti’s story, as a Jewish doctor working under a false identity while helping to hide other Jews, attracted growing attention from researchers.

In recent years, documentaries and articles have brought the story to a wider audience. Some popular retellings have added dramatic flourishes or simplified timelines, which has led historians to stress what is firmly documented and what rests on later recollection. The core facts, however, are well supported: Fatebenefratelli hid Jews, invented a fake disease as a cover, and used that fiction to scare off Nazi inspections.

So what? The gradual uncovering and recognition of Syndrome K show how many acts of rescue in the Holocaust remained quiet for decades, and how memory, testimony, and archival work can bring them into the historical record.

Why Syndrome K still matters today

Syndrome K is often summarized in a single sentence: “Italian doctors invented a fake disease to save Jews from the Nazis.” That line travels well on social media because it is neat, ironic, and satisfying.

The fuller story is messier and more human. It involves a compromised regime, an occupying army, religious institutions, personal risk, and the daily grind of hospital work under war conditions. It is not a fairy tale. Some Jews in Rome were saved. Many others were not.

What makes Syndrome K worth remembering is not just the cleverness of the ruse. It is the way a small group of people used the tools they had, in the place they were, to push back against a system built for murder. They did not blow up trains or lead armed uprisings. They filled out charts, invented diagnoses, and taught terrified refugees how to cough on cue.

The story also punctures the myth of Nazi omnipotence. The occupiers were brutal, but they were not all-knowing. They were afraid of disease. They relied on local institutions they did not fully control. In that gap between power and perception, there was room for resistance.

For medicine, Syndrome K raises hard questions that are still relevant. When does a doctor’s duty to protect life justify lying to authorities or bending rules? How should hospitals act under regimes that target parts of their population for persecution? Those are not abstract questions in a world where medical professionals still work under dictatorships and in war zones.

On Tiber Island in 1943, three doctors and a handful of brothers answered those questions in their own way. They wrote “Sindrome K” on a chart, told their patients to cough, and watched the soldiers turn away.

So what? Remembering Syndrome K keeps alive a specific example of quiet, risky resistance, and reminds us that even in systems built for mass violence, small acts of deception and courage can open real space for survival.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was Syndrome K in World War II?

Syndrome K was a fictitious disease invented in 1943 by doctors at Fatebenefratelli Hospital in Rome. They used it as a fake diagnosis to hide Jewish refugees and political fugitives from Nazi roundups by claiming the patients had a dangerous, contagious illness.

Who created Syndrome K and where did it happen?

Syndrome K was created by doctors Giovanni Borromeo, Adriano Ossicini, and Vittorio Emanuele Sacerdoti at Fatebenefratelli Hospital on Tiber Island in Rome during the Nazi occupation of the city.

Did Syndrome K really save Jews from the Nazis?

Yes. Survivor testimonies and historical research indicate that dozens of Jews were admitted to Fatebenefratelli Hospital under the fake diagnosis of Syndrome K. When Nazi soldiers came to search the hospital, the supposed contagious nature of the disease helped scare them away from the ward where these people were hiding.

Why was it called Syndrome K?

The exact origin of the name is not fully certain. Several accounts from the doctors involved say the “K” was a dark joke referring to Nazi officials Albert Kesselring and Herbert Kappler. Historians accept that explanation as plausible, though precise documentation from the time is limited.