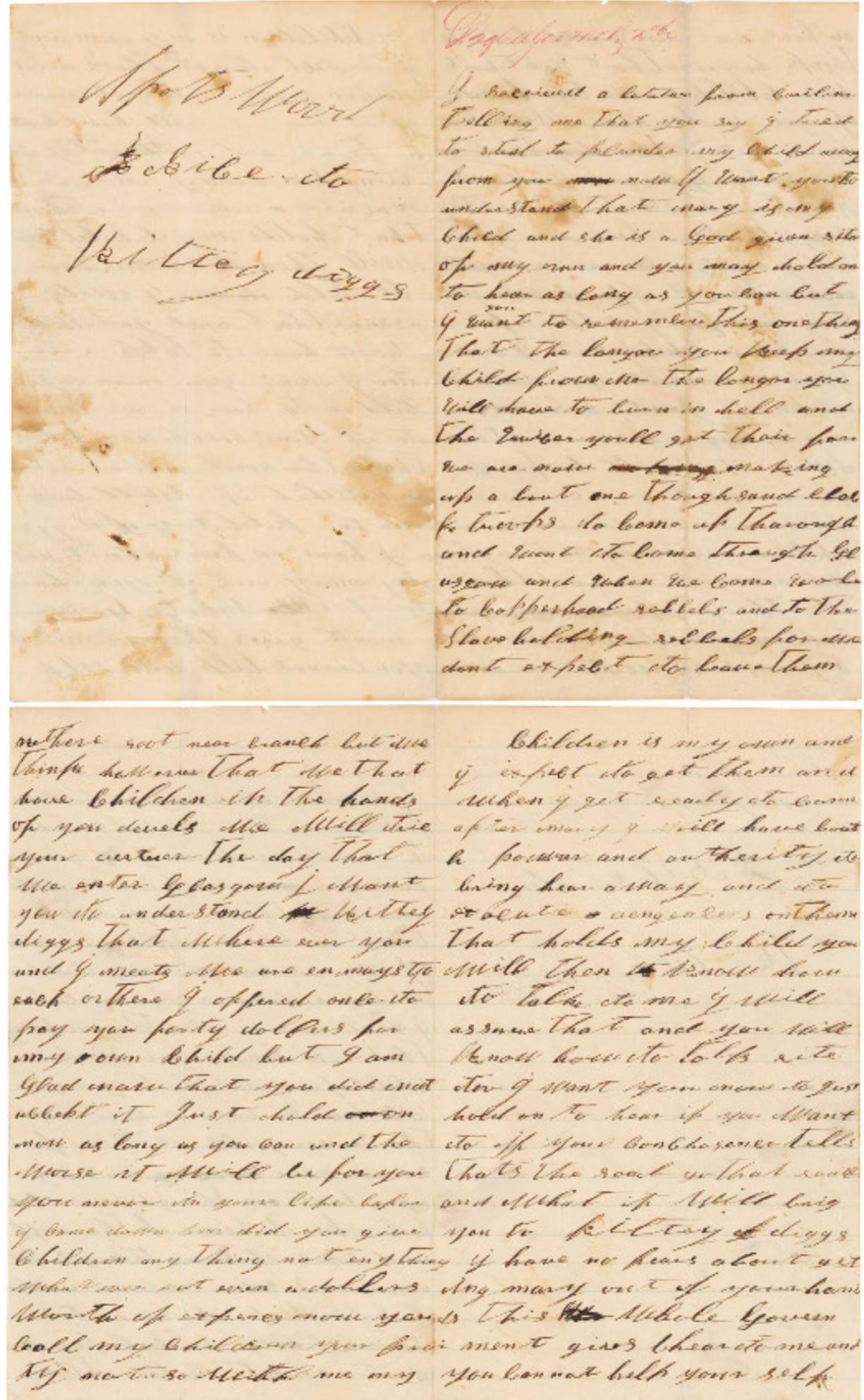

September 3, 1864. A Black Union soldier sits down somewhere in Missouri and writes to the woman who used to own him.

He does not ask. He does not beg. He threatens.

“Mary is my Child and she is a God given rite of my own,” he tells Katherine “Kitty” Diggs, who still holds his daughters in slavery. He warns her that an army of Black troops is coming through Glasgow, Missouri, and that “wo be to Copperhood rabbels and to the Slaveholding rebbels.” He promises to “exacute vengencens on them that holds my Child.”

This is Spotswood Rice, a formerly enslaved man turned Union soldier, writing a letter that would survive in the National Archives and, 160 years later, go viral on Reddit. It is raw, misspelled, and absolutely clear about what the Civil War had become for people like him: a war to get his children back and punish those who claimed to own them.

Here are five things that letter reveals about slavery, the Civil War, and what freedom actually meant.

1. The Civil War Turned Enslaved Parents Into Military Liberators

What it is: Spotswood Rice’s letter shows how the Civil War turned enslaved parents into active liberators of their own families, not just passive recipients of freedom granted by others.

In the letter, Rice tells Diggs bluntly that he is coming back with “bout one thoughsand blacke troops” and that he expects to bring his daughter Mary away “with powrer and autherity.” He is not asking a favor from a former owner. He is announcing a military operation.

That shift did not happen overnight. Rice had been enslaved in Missouri, a slave state that stayed in the Union. At some point in 1863 or 1864, he escaped and enlisted in the Union Army. Records show a Spotswood Rice serving in the 67th U.S. Colored Infantry, a regiment of Black soldiers raised in Missouri.

By the time he wrote this letter in September 1864, the war had changed. The Emancipation Proclamation had been in effect for more than a year and a half. The Union had begun recruiting Black men in large numbers. Those men did not just fight anonymous Confederates. Many, like Rice, aimed their new status and their rifles back at the exact people who had owned them and still held their families.

You can hear that in the way he talks about the coming Black troops. He writes of “we that have Children in the hands of you devels.” That is not abstract patriotism. It is a rescue mission.

Other examples echo Rice’s story. In 1864, Black soldiers in the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry fought near their former plantations in Arkansas. In Louisiana, men of the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guard regiments marched past sugar plantations where they had once labored. In South Carolina, men of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers (later the 33rd USCT) helped free enslaved people on the Sea Islands where they themselves had been held.

For many enslaved Americans, the Civil War was not just a national conflict. It was a chance to come back armed, in uniform, and change the power dynamic with the people who had controlled their lives.

So what? Rice’s letter makes visible a basic truth: emancipation was not only something done by Lincoln and Congress. Enslaved people, once armed, used the war to liberate their own families and confront their former owners directly.

2. Slavery Tried To Erase Black Parenthood, And People Like Rice Refused

What it is: The letter is a fierce assertion of Black parental rights in a system that treated enslaved children as property, not as sons and daughters.

Over and over, Rice insists that Mary is his child, not Diggs’s property. “Mary is my Child and she is a God given rite of my own,” he writes. He reminds Diggs that she never paid “even a dollers worth of expencs” for his children, yet she now calls them her property.

Under American slavery, the law followed the mother. Children born to enslaved women were automatically enslaved, no matter who the father was. Enslavers sold children away from parents as a matter of routine. No legal recognition of Black marriages. No legal protection for Black families.

Missouri was no exception. Enslaved families in counties like Howard and Chariton, near Glasgow, were frequently broken up by sale or inheritance. Letters and bills of sale from the era talk about “boy, age 10” or “girl, age 7” as assets, not as children with parents who loved them.

Rice’s letter pushes back against that entire logic. He is not just angry that Diggs will not let Mary go. He is furious at the idea that she thinks she has any claim at all. “My Children is my own and I expect to get them,” he writes. That is a moral claim, but in 1864 it is also a political and legal one. The Union government, through emancipation and military policy, is beginning to recognize Black families as families, not as herds of property.

His case was far from unique. In 1865, thousands of freed people wrote to the Freedmen’s Bureau or traveled miles to find children sold away. A woman named Letty in Virginia searched for her son Lewis, sold before the war. Men like Jourdon Anderson, who wrote a famous sarcastic letter to his former master in Tennessee, talked about their wives and children as central to their new freedom.

Rice’s anger at Diggs is not just personal spite. It is a father insisting that a system built to erase his parenthood has no more authority.

So what? The letter shows that emancipation was deeply about family. Freedom meant the right to claim your own children, to refuse the fiction that they were anyone’s property but yours.

3. Black Faith Fueled Both Mercy And Threats Of Hellfire

What it is: Rice’s language shows how Black Christian belief shaped both his sense of justice and his threats against slaveholders.

He tells Diggs that “the longor you keep my Child from me the longor you will have to burn in hell and the qwicer youll get their.” That is not just colorful language. It reflects a religious worldview that many enslaved and freed people shared: God would judge slaveholders, and the war itself might be part of that judgment.

Enslaved people in the antebellum South often embraced a version of Christianity that emphasized the Exodus story, divine justice, and the idea that God stood with the oppressed. White slaveholders tried to use the Bible to justify slavery. Black preachers and laypeople read the same text and found a God who freed captives and punished Pharaohs.

Rice was no exception. After the war, he became a Methodist minister in Missouri and Colorado. His postwar sermons, where they survive, keep the same mix of moral certainty and plain speech that shows up in this 1864 letter.

In the letter, he links his personal cause to a larger divine order. He calls slaveholders “you devels.” He frames the Union government as backing him up: “this whole Government gives chear to me and you cannot help your self.” For him, the United States and God are aligned, at least on this question: he has a right to his children, and those who deny that right will face both earthly and eternal consequences.

Other Black soldiers and freedpeople used similar language. Frederick Douglass spoke of the war as “the wrath of Almighty God” on a guilty nation. Black Union chaplains preached that enlisting to fight slavery was a Christian duty. Spirituals like “Go Down, Moses” cast slaveholders in the role of Pharaoh, doomed to defeat.

Rice’s threats of hellfire are not just personal rage. They are part of a broader Black religious tradition that saw slavery as a sin and expected God to act, often through human hands.

So what? The letter reminds us that Black faith during the Civil War was not passive or quietist. It gave people like Rice the language to condemn slavery as evil, to see the Union war effort as righteous, and to promise judgment on those who clung to human bondage.

4. Literacy And Spelling Did Not Equal Power. His Voice Did.

What it is: The rough spelling in Rice’s letter often fascinates modern readers, but the content shows how enslaved and formerly enslaved people used limited literacy as a weapon.

The letter is full of phonetic spellings: “leteter,” “qwicer,” “autherity,” “rebbels.” To a 21st-century eye, it can look like a wall of errors. To a 19th-century eye, especially a white one, it might have been easy to sneer at. Yet there is no mistaking what he is saying.

Enslaved people in slave states were often forbidden by law or custom to learn to read and write. In some states, teaching an enslaved person to read could bring fines or violence. Missouri did not have the harshest anti-literacy laws, but opportunities were still scarce. A man like Rice probably picked up what he could from other enslaved people, sympathetic whites, or, later, the army.

By 1864, the Union Army had become an unlikely literacy school. Chaplains, officers, and Northern aid workers taught Black soldiers to sign their names, read orders, and write letters. Many of the surviving letters from Black soldiers to their families were written with help from comrades or white clerks, but the ideas and words were their own.

Rice’s letter, with its distinctive spelling and grammar, feels like something he wrote himself or dictated to someone who wrote it as he spoke. The spelling does not blunt the force. If anything, it makes his voice louder across the years. He is not performing for educated Northerners. He is talking straight to the woman who used to own him.

And he knows exactly what he is doing. He reminds Diggs that he once offered her forty dollars for Mary and that she refused. He mocks her conscience. He lays out a clear threat: when he comes, he will have legal and military authority behind him.

Other Black writers of the era, like Harriet Jacobs or Douglass, had polished prose shaped by abolitionist editors. Rice’s letter is different. It is unfiltered. It shows how even limited literacy could be turned into a tool of resistance, a way to fix threats and claims on paper.

So what? The spelling quirks that catch Reddit’s eye are part of the story, but not the heart of it. Rice’s letter shows that power came from the ideas he put on the page, not from conforming to white standards of grammar.

5. The Union Government Backed Him, And Slaveholders Knew It

What it is: Rice’s confidence that “this whole Government gives chear to me” reflects a real shift in federal policy, and it terrified people like Katherine Diggs.

When the war began in 1861, the Lincoln administration insisted it was fighting only to save the Union, not to end slavery. By 1864, that had changed. The Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863, declared enslaved people in Confederate-held areas free and authorized their enlistment in the Union Army.

Missouri was a special case. It stayed in the Union, so the Proclamation did not directly apply. Enslaved people there were legally freed by a state constitutional convention in January 1865. But long before that, Union officers in Missouri were sheltering runaways, enlisting Black men, and treating enslaved people who reached their lines as effectively free.

Rice had experienced that shift firsthand. Once he put on a Union uniform, he was a soldier of the United States, not someone’s property. His pay was often lower and delayed compared to white soldiers, but on paper he was part of the same army. When he wrote that he would come with “powrer and autherity,” he meant the power of that army and the authority of the federal government.

Slaveholders like Diggs could feel the ground moving. Union troops had already operated in and around Glasgow, Missouri. In October 1864, just weeks after Rice’s letter, the town would be the site of a battle during Confederate General Sterling Price’s raid. Control of Missouri was contested, and enslavers knew that Union victories brought more runaways and more Black enlistments.

Rice is blunt about what that means for Diggs. “You cannot help your self,” he tells her. He is not just threatening personal revenge. He is pointing out that the legal and military tide has turned. The people who once had the law on their side are now the ones defying it.

After the war, that federal backing would become formal. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery nationwide in December 1865. The Freedmen’s Bureau, created in March 1865, helped reunite families and enforce new labor contracts. Men like Rice could appeal to courts and federal agents, not just to their own courage.

His letter catches the moment when that shift was still in motion, when a former slave could write to a current slaveholder and say, with some accuracy, that the government was with him, not her.

So what? The letter is a snapshot of federal power changing sides. It shows how Union policy turned from protecting slaveholders’ rights to backing the claims of people they had owned, and how Black soldiers used that shift to press their own demands.

Why Spotswood Rice’s Letter Still Hits Hard

Spotswood Rice did get his children back. Records suggest that his daughters Mary and Caroline were freed by the end of the war. He went on to preach, move west, and live as a free man who had once threatened his former owner with both the Union Army and the fires of hell.

The letter survives because the National Archives preserved it as part of Confederate or Union records. It circulates online now because it does what a lot of official Civil War documents do not: it puts you inside the mind of someone who had everything at stake.

It reminds us that slavery was not an abstract system. It was a woman claiming that someone else’s child was her property. It was a father calculating whether to offer forty dollars for his own daughter. It was a man in uniform telling the person who used to own him that the next time they met, they would be enemies.

And it shows that emancipation was not just a line in a proclamation. It was a thousand personal confrontations like this one, where the old order met the new, and the people who had been written out of the story picked up a pen and wrote themselves back in.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was Spotswood Rice in the Civil War?

Spotswood Rice was a formerly enslaved man from Missouri who escaped slavery and enlisted in the Union Army, likely in the 67th U.S. Colored Infantry. In 1864 he wrote a famous letter to his former owner, Katherine Diggs, vowing to return with Black troops to free his enslaved children.

Did Spotswood Rice really threaten his former owner?

Yes. In a letter dated September 3, 1864, Rice told Katherine Diggs that he would come back with about a thousand Black troops, free his daughter Mary, and “exacute vengencens” on those who held her. He warned that the longer she kept his child, the longer she would “burn in hell.”

What happened to Spotswood Rice’s children Mary and Caroline?

Sources indicate that Mary and Caroline were freed by the end of the Civil War, likely as Union control and emancipation policies reached Missouri. Details of their exact path to freedom are sparse, but Rice’s postwar life as a free man and minister suggests he was reunited with them.

Why is Spotswood Rice’s 1864 letter important today?

The letter is important because it shows how enslaved people used the Civil War to free their own families, asserted their rights as parents, and confronted former owners. It captures the shift in federal power toward emancipation and gives a rare, unfiltered voice to a Black soldier demanding his children back.