The Siege of Boston began the American Revolution, beginning on April 1775 and lasting until March 1776. Colonial militiamen were able to successfully say siege to Boston, which was being held by the British at the time. General George Washington had arrived in Boston in July to take charge over the new Continental Army as both sides dealt with supply and personnel issue throughout the entirety of the siege. Eventually, the British abandoned Boston eleven months after the siege had begun, marking the official end on March 17, 1776.

Tensions had been building between Britain and the colonists in America for over a decade at this point. When the British began taxing the colonists with the Stamp Act and the Townshend Acts, the colonists were furious over taxation without representation. To make matters worse, a resistance in Boston in 1770 ended with the death of five men when the British opened fire on a mob of angry colonists. This became known as the infamous Boston Massacre,

A group of patriots in Boston gathered together in December of 1773 to dump hundreds of chests of tea from British ships into the Boston Harbor in response to the Tea Act. The Boston Tea Party remains to be one of the well known events that led to the American Revolution. In response, 4,000 British troops were sent under command of General Thomas Gage to occupy the city. On the colonists side, a group of delegates that consisted of George Washington, Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, John Jay, and more gathered in Philadelphia in 1774, the First Continental Congress.

While the First Continental Congress did not yet demand independence from Britain, they denounced taxation without representation and the British army in the colonies without consent. They also declared that each citizen deserved the rights such as life, liberty, property, assembly, and trial by jury. At the end of the meeting in October, the Continental Congress voted to meet again the following May.

British forces were sent to Concord, Massachusetts on April 19, 1775 to seize military supplies, but militias from surrounding towns opposed them. On their way back to Boston, the British troops suffered many casualties. The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolution and ended with a strategic American victory. After the battle, all the New England colonies, with the Southern colonies to follow, raised militias to send to Boston immediately.

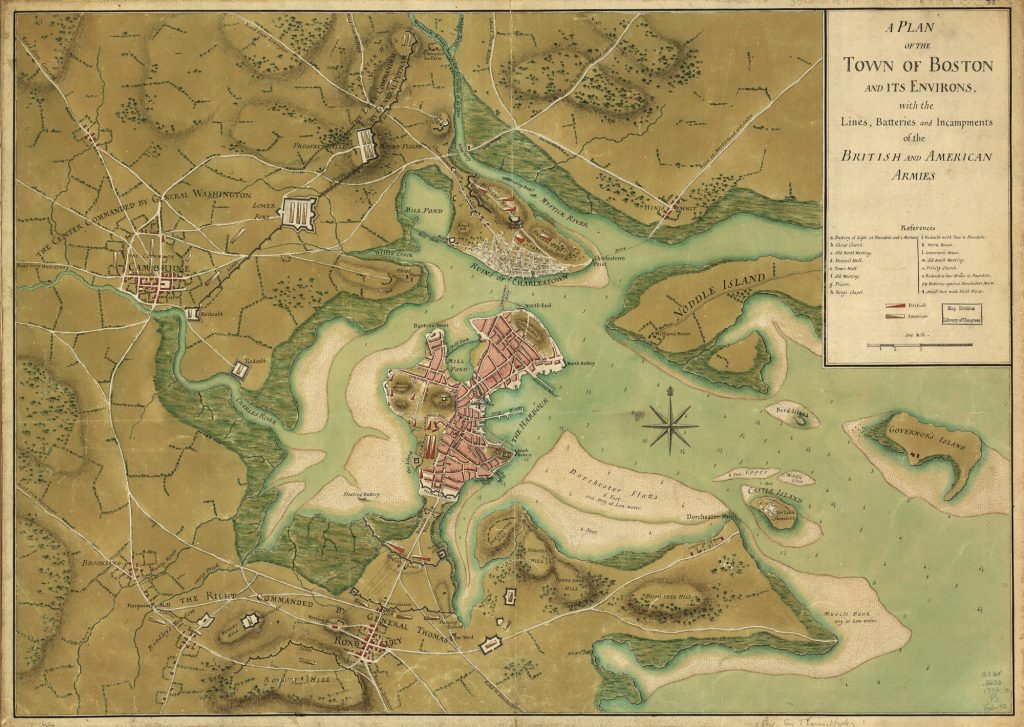

The Massachusetts militia formed a siege line around the Boston and Charlestown peninsulas that extended from Chelsea to Roxbury under William Heath’s leadership. The were able to effectively surround Boston on three sides except for the harbor and seas, which were under British control. Militias from Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island soon arrived and the colonial forces only grew more and more.

Turning his attention to fortifying easily defendable positions, General Gage ordered lines of defenses with ten twenty-four pound guns at Roxbury. The British promptly fortified four hills in Boston proper. These would serve as the city’s main defense points. The hills were strengthened over time as well. In the meantime, Gage decided to remove the forces from Charlestown to Boston, altogether abandoning Charlestown. They left Charlestown empty and Bunker Hill, Breed’s Hill, and the heights of Dorchester undefended.

Originally, the British greatly restricted any movement in and out of Boston. They feared the infiltration of weapons. Eventually, they reached an agreement to allow traffic on the Boston Neck as long as no firearms were carried. Bostonians quickly turned in nearly 2,000 muskets and majority of the Patriots fled the city. As the patriots fled the city, Loyalists from outside the city came swarming in. Now that the Patriots were in control of the countryside, the Loyalists feared that they were no longer safe. Some Loyalist men even joined lOyalist regiments that were attached to the British Army.

Under Vice Admiral Samuel Graves, the Royal Navy was able to sail in supplies from Nova Scotia, among other locations, due to the harbor not being blocked off. Because of the British fleet’s naval supremacy, there was nothing the colonists could really do to put an end to this. American privateers were able to harass any supply ships however. As food prices quickly rose due to shortages, the British were on short rations. The Americans were also easily able to gather information about any happenings inside the city from people fleeing Boston. General Gage had no effective information on the Americans though.

Benedict Arnold was authorized to raise forces to bring to Fort Ticonderoga in New York on May 3, 1775 by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. Fort Ticonderoga had a reputation for its heavy weapons and light defenses. On the 9th, Arnold arrived in Castleton (now apart of Vermont) and joined Ethan Allen and a Connecticut militia company. They had all arrived on their own with the idea of taking Ticonderoga. Under the joint leadership of Arnold and Allen, the militia company captured both Fort Ticonderoga and Fort Crown Point. Along with capturing the forts, they also captured a large military vessel on Lake Champlain when they were raiding Fort Saint-Jean in Canada. Along with other weapons and supplies that would prove useful for the Continental Army holding onto Boston, they recovered more than 180 cannons.

In Boston, they were lacking a regular supply of fresh meat and did not have enough hay for all the horses. Gage ordered for a party to travel to Grape Island, which was located in the outer Boston harbor, on May 21. The Continentals soon noticed this and called out the militia. As soon as the British party arrived on the island, they found themselves under fire from the militia. The militia ended up destroying 80 tons of hay when they set fire to the island’s barn.

Partially in response to what had happened on Grape Island, Continentals worked on clearing out any livestock or supplies the British might have found useful on the other harbor island. In an attempt to stop the removal of livestock from some islands, the British Marines fought the Continentals in the Battle of Chelsea Creek, the second military engagement of the Siege of Boston, on May 27-28,1775. The battle resulted in American victory. On June 12, General Gage then sent out a proclamation offering to pardon anyone, except for John Hancock and Samuel Adams, who laid down their arms. By doing this, he had hoped to quell the rebellion, but instead he was met with more angry Patriots who began to take up more arms.

Throughout the month of May, reinforcements were being sent from Britain to the colonies until the British Army reached a strength of 6,000 in Boston. Three well known generals all arrived in the city on May 25 on the HMS Cerberus, John Burgoyne, Henry Clinton, and William Howe. Meanwhile, General Gage had started planning on breaking out of Boston.

Their plan was to fortify Bunker Hill along with Dorchester Heights on June 18. Three days before the fixed date, the Committee of Safety, which took control of the colonies away from royal officials, learned of these plans. They sent General Artemas Ward instructions to fortify both Bunker Hill and the heights of Charlestown. Colonel William Prescott was given the order to carry out these instructions. Preston led about 1,200 men over the Charlestown Neck on June 16 and constructed fortifications and Bunker Hill and Breed’s Hill.

In the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775, General Howe’s British forces took the Charlestown peninsula. However, the British also suffered significantly more casualties than the Continentals. A total of 1,054 men were either killed or wounded, while the Americans suffered 450 casualties overall. Due to such heavy losses during the battle, they were no longer able to directly attack the Americans. When they had began losing the battle, the Americans stood against the British somewhat successfully and were able to ward off two assaults on Breed’s Hill. The battle ended with a British victory, despite their many losses and casualties, including the death of 19 officers.

On July 2, General George Washington arrived at Cambridge, Massachusetts. He set up camp at Harvard College in the Benjamin Wadsworth House. And the following day, he became the leader of the Continental Army. Forces and supplies were also beginning to arrive. Companies of riflemen all the way from Virginia and Maryland joined the Continentals in Boston. Washington started working on combining the many militias to more closely resemble an army. While militias elected their leaders, Washington appointed senior officers and introduced more organization and discipline to the militiamen. Officers of different ranks were now required to wear different uniforms to more easily be distinguished from those below and superior to them.Washington then moved his headquarters to John Vassall House (later Henry Wadsworth Longfellow) on July 16. By the end of the month, around 2,000 riflemen had arrived from Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia.

Trenches in Boston Neck were dug up to extend towards Boston when Washington ordered for improving defenses. These activities and improved defenses did not have much effect on the British. The British burned a few homes in Roxbury on July 30 when they pushed back an American advanced guard. Only a few days later, an American rifleman was killed on August 2 and they hung up his body by the neck. In response, other American riflemen marched up to the lines to attack the British. All day, they continued sharp shooting at the British, wounding and many. At the end of the month on the 30th, a surprise breakout was made by the British from the Boston Neck when they set fire to a tavern and withdrew their defenses. That same night, 300 American men burned the lighthouse on Lighthouse Island and killed several british while capturing twenty-three and only losing one of their own. Another night that month, Washington had sent about 1,200 of his men near charlestown Neck to dig entrenchments on the hill. Even with a bombardment from the British, they were successfully able to dig the trenches.

Washington began drawing up plans in early September for two moves. First they would dispatch 1,000 men to invade Quebec from Boston and secondly they would launch an attack on Boston. After receiving intelligence from British deserters and Americans spies that the british were not intending to launch an attack on Boston until reinforcements arrived, Washington felt confident in sending some of his men to Quebec. Later that month, Benedict Arnold was put in command of about 1,100 men and left for Quebec on September 11. Washington, still in Boston, summoned a council of war to make an all out assault on Boston. They would send troops across Black Bay about fifty at a time in flat bottomed boats. Washington believed that to keep the men together upon the arrival of winter would be extremely difficult. In the end, his plan was unanimously rejected by the war council anyway.

In early September, Washington had also authorized appropriating and outfitting local fishing vessels to gather intelligence and British supplies. This activity later led into the Continental Navy, which would later be established after the British Burning of Falmouth in October of 1775. At that point, the provincial assemblies of both Connecticut and Rhode Island had started to arm ships and authorize privateering.

400 British soldiers went on a raiding expedition to Lechmere’s Point in early November in hopes of acquiring livestock. While they had been able to take 10 cattle, they lost two lives in a skirmish with colonials that had been sent to defend the point. Later that month on November 29, commander of the schooner Lee, colonel Captain John Manley, captured one of the most valuable items of the Siege of Boston, Nancy, a British brigantine outside Boston Harbor. The sip had been carrying a large supply of military stores and ordnance for the British.

Both sides faced problems as winter approached. In the event of a British account, American soldiers were forced to use spears because they were too short on gunpowder. Many of the Americans remained unpaid throughout the war and most of their enlistments were up at the end of the year. Due to the scarcity of wood, they cut down trees and tore down wooden buildings, one of them being the Old North Meeting House. And, it was more and more difficult to supply the city because of winter storms and the many rebel privateers. The British troops were preparing to desert from constant hunger. On top of all that, scurvy and smallpox had broken out in Boston. Washington faced many problems as his soldiers from rural communities were being exposed to smallpox. He moved the infected troops to a separate hospital.

In February the water between Roxbury and Boston Common had frozen. Washington had been waiting since October for the harbor to freeze to go through with a proposed assault on the city. He thought that by rushing across the ice they could try an assault, even with the shortage of gunpowder. Once again, his office advised him not to go through with the assault. Washington’s desire to launch an assault on the city had been due to fear that his army would desert him and that Howe could easily break the lines of the army in the state it was in. With great reluctance, Washington abandoned the plan to attack across the ice to come up with a safer plan. Instead, they would fortify Dorchester Heights with cannons that had arrived from Fort Ticonderoga.

British Major General Henry Clinton sent a small ship to the Carolinas with about 1,500 men on orders from London in mid-January. The objective of this was to join forces with additional troops on their way from Europe and to then take a port in the southern colonies. Several farmhouses were then burned in Dorchester in early February by a British raiding party.

In February of 1776, Colonel Henry Knox and a team of engineers returned from a trip using sledges to retrieve 60 tons of heavy artillery from Fort Ticonderoga. They had left for this mission in November of 1775. After crossing the frozen Hudson and Connecticut Rivers in a very technically challenging operation. On January 25, 1776, they arrived back in Cambridge.

The American troops began placing some of the cannons from Ticonderoga on the night of March 2, 1776. They began bombarding the city with the cannons. In response, the British responded with their own cannons. Under Colonel Knox’s direction, the Americans continued to exchange fire with the British for two days. Little damage was done to either side. A few houses were damaged and some British soldiers in Boston were killed as well. Washington moved more of the Ticonderoga cannons and several thousand of his men to occupy Dorchester Heights overnight. Dorchester Heights overlooks Boston. Digging trenches was impractical due to the frozen ground, so Washington’s men used logs, branches, and anything else they could find to fortify their position overnight instead. Both the city and the troops were at risk because the British fleet was in range of American guns.

The British started a two-hour cannon barrage at Dorchester heights immediately after, thouse this had no effect because the American guns were too high for the British to reach. Howe and his officers agreed that if they were to hold boston, they must remove the colonists from the heights right after the barrage. They planned an assault on the colonists on Dorchester Heights, but it never went through due to a storm. The British decided to withdraw instead.

Bostonians sent a letter to Washington on March 8th in fear that the city would be destroyed from the British. Though he was given the letter, Washington formally rejected it because it had not been addressed to him by name or title. The letter did have the intended effect though. Upon the beginning of the evacuation, the British departure was unable to be hindered by any American fire.

After seeing movement on Dorchester on Nook’s Hill, the British opened a massive fire barrage on March 9 that lasted through the night. Four men were killed with one cannonball, but luckily no other damage was done. The following day, the colonists collected the cannonballs the British had fired at them, about 700 total.

General Howe issued a proclamation of March 10 that ordered for the Bostonians to give up any linen and woolen goods that the colonists may have used to continue the war. Loyalist Crean Bush was authorized to receive these goods and in return he gave worthless certificates. Over the course of the next week, the British fleet sat and waited in Boston harbor as they waited for favorable winds. British soldiers and Loyalists were being loaded onto the ships as they waited. Meanwhile, the Americans successfully conducted naval activities in the boston harbor and were able to diverted many British supply ships to ports under Colonist control. The winds turned favourable on March 15, but before the British could leave, the winds turned against them. Once again, the wind became favorable two days later. The troops were given permission to burn the town in case of any disturbances as they marched to their ships. The British began moving out by 4:00 a.m. and all ships were underway five hours later at 9:00 a.m. 120 ships with over 11,000 people aboard departed Boston. Of these passengers, 9,906 were men with 667 women and 553 children.

The Americans moved to begin reclaiming Boston and Charlestown after the British fleet left the harbor. At first, they believed the British to still be on Bunker Hill, but they realized that those were just dummies left behind. Because they ran the risk of coming in contact with smallpox, only men with previous exposure to the disease entered Boston under Artemas Ward’s command. When the risk of disease was lower, more colonials entered the city on March 20. Washington had made sure that the British’s departure of the harbor wasn’t too easy. Captain Manley was directed to harass the departing fleet and was somewhat successful, capturing the ship that carried Crean Brush and the goods he had collected before their departure.

Once his fleet left the outer harbor, General Howe left a small amount of vessels to intercept any incoming British vessels. They successfully redirected many ships carrying British troops to Halifax instead of Boston. When some unsuspecting troops landed in Boston, they found themselves falling into the hands of the Americans.

For his failures during the Siege of Boston, General Howe was greatly criticized in both British press and Parliament, though he remained in command for two more years to come and led the New York and New Jersey Campaign and the Philadelphia Campaign. General Gage was never given another combat command and General Burgoyne saw action in the Saratoga Campaign that ultimately led to his capture. General Clinton commanded the British forces after Howe from 1778-1782 when the war ended.

Many Loyalists in Massachusetts left with the British. Some went to rebuild their lives in England and some returned to America following the war. Most stayed in Nova Scotia and settled in places like Saint John, becoming active later on in the development of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

Boston was no longer a military target after the siege. It did continue to be a focus point for many activities during the war though. Its port was an important point for fitting war ships and privateers. Boston’s leading citizens later played roles in developing the United States after the war. Today people in Boston and surrounding communities celebrate March 17 as Evacuation Day in honor of when the siege ended.