In the summer of 1219, on a field near modern Tallinn, a Danish army fought Estonian forces while their king, Valdemar II, directed the battle. According to later legend, a red flag with a white cross fell from the sky and promised victory. That flag, the Dannebrog, is still Denmark’s national flag today.

This was not a Viking raid. It was a Christian crusade, backed by the pope, aimed at conquering and converting the eastern Baltic. The raiders of the ninth century had become kings, crusaders, and empire builders. Far from fading into irrelevance, Scandinavia had simply changed costume.

So what actually happened to Scandinavia after the Viking Age? During the High Middle Ages, roughly 1000–1300, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden were not running wild on the Atlantic anymore, but they were very much in the game: fighting in the Baltic, shaping trade routes, joining European dynastic politics, and experimenting with early state-building. By the end of this story, Scandinavia had shifted from a feared fringe to a plugged-in, if still awkward, member of Latin Christendom.

What was Scandinavia during the High Middle Ages?

When people say “Scandinavia after the Viking Age,” they usually mean the kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden from about 1000 to 1300. The Viking Age, in a narrow sense, runs from the late 8th century to the mid-11th. After that, raiding declines, large-scale overseas expansion stops, and the political map hardens into three Christian monarchies.

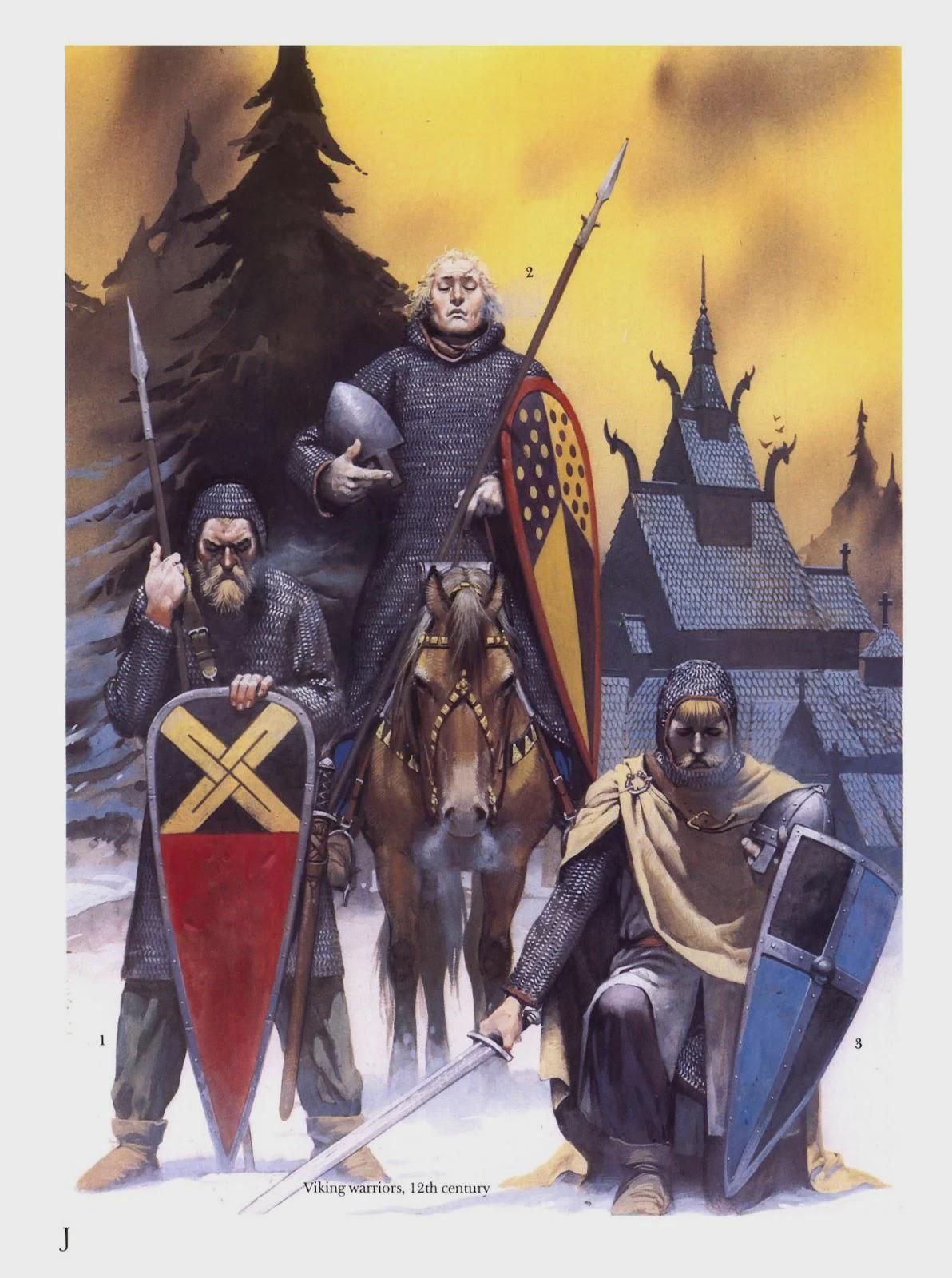

By the 12th century, each kingdom had a king, a Christian church hierarchy, and some form of law code. They were no longer loose networks of chieftains sending ships abroad. They were territorial states, however fragile, competing with neighbors like the Holy Roman Empire and the emerging kingdoms of England and Poland.

Scandinavia in the High Middle Ages was a cluster of Christian monarchies tied into European trade, crusading, and dynastic politics, especially around the Baltic Sea. The raiders had become landlords, bishops, and tax collectors. This matters because it shifts the question from “why did the Vikings disappear?” to “how did these northern kingdoms fit into the same political world as France or Hungary?”

What set this transformation off after the Viking Age?

The short answer: Christianity, centralization, and changing economics.

First, Christianization. Denmark’s King Harald Bluetooth famously claimed to have “made the Danes Christian” in the late 10th century. Norway’s conversion is tied to kings like Olaf Tryggvason and Olaf Haraldsson (later St Olaf), who died in 1030. Sweden’s process was slower and more contested, but by the 12th century all three kingdoms were firmly in the Latin Christian orbit, with bishops, monasteries, and ties to the papacy.

Conversion did not just change religion. It plugged Scandinavia into a wider legal and ideological world. Kings could now claim divine sanction, mint coins with Christian symbols, and receive papal support against rivals. The church brought literacy, record keeping, and a new class of clerical administrators. That made more stable, more centralized kingdoms possible.

Second, the old Viking business model stopped working as well. As England, Francia, and the Slavic coasts fortified and organized, raiding became less profitable and more dangerous. At the same time, internal trade, agriculture, and tolls on Baltic routes became more attractive sources of income. You can see this in the growth of towns like Lund, Bergen, and Visby.

Third, there was pressure from outside. The Holy Roman Emperors and their Saxon nobles pushed north and east, conquering and converting Slavic groups on the southern Baltic coast. If the Scandinavian kings did not organize, they risked being boxed in or even conquered. That fear helped drive them to tighten control over their own elites and look east for expansion.

So the same forces that ended the Viking Age, Christianization and stronger neighbors, pushed Scandinavia to reinvent itself as a set of Christian kingdoms focused on the Baltic and internal consolidation. That matters because it explains why “Viking” activity fades while Scandinavian power does not.

What was the turning point: from raiders to Baltic powers?

There is no single day when Scandinavia “stopped being Viking,” but a few turning points mark the shift.

One is the defeat of the last major Scandinavian attempt to dominate England. In 1066, Harald Hardrada of Norway invaded England but died at Stamford Bridge. Weeks later, William of Normandy, himself descended from Vikings, conquered England. From then on, English kings were no longer easy prey for Scandinavian fleets. The Atlantic adventure was closing.

Another turning point is the consolidation of royal power and law. In Norway, King Magnus Lagabøte (“Law-mender”) issued a national law code in the 1270s, one of the earliest such codes in Europe. In Sweden, provincial laws were written down from the 13th century, and a more unified realm emerged under kings like Birger Jarl. Denmark had already been relatively centralized under kings like Valdemar I and Valdemar II in the 12th and early 13th centuries.

At the same time, the focus of expansion shifted east. Instead of sailing to York or Dublin, Scandinavian rulers and nobles looked to the Baltic. The so-called Northern Crusades, from the late 12th century onward, targeted pagan groups around the eastern Baltic: Finns, Livonians, Estonians, Prussians. Danes, Swedes, and their German neighbors all joined in.

Denmark’s conquest of northern Estonia in 1219, Sweden’s campaigns in Finland, and the growth of Visby on Gotland as a major trading hub all show the new orientation. The Baltic Sea became “a Scandinavian lake” only in a loose sense, since German merchants and the Teutonic Order were also major players, but it was the main arena for Scandinavian ambition.

This matters because it explains why Scandinavia seems to vanish from the English and French chronicles that shape many popular narratives. The action moved to the Baltic and to internal politics, not to the English Channel or the Seine.

Who drove this era: kings, crusaders, and traders

Several figures and groups shaped Scandinavia’s High Medieval story.

1. The Valdemars of Denmark

Valdemar I (r. 1157–1182) and his son Valdemar II (r. 1202–1241) turned Denmark into the most assertive Scandinavian kingdom of the 12th–13th centuries. They crushed internal rivals, allied with the church, and pushed into the Baltic.

Valdemar I, with his advisor-bishop Absalon, attacked the pagan Slavic Wends along the southern Baltic coast. They destroyed the stronghold at Arkona on the island of Rügen in 1168, a symbolic blow against Slavic paganism. Valdemar II followed up with campaigns in Holstein and Estonia. For a brief period, Denmark controlled much of the southern Baltic coast and northern Estonia.

The Valdemars matter because they show a Scandinavian kingdom acting like a regional great power, mixing crusade rhetoric with very practical territorial expansion.

2. Norwegian kings and the Atlantic world

Norway did not vanish into the fjords. It kept a looser but real hold over the North Atlantic islands: Iceland, Greenland, the Faroes, and the Hebrides. In the 13th century, Norwegian kings formalized this. The Old Covenant of 1262–64 brought Iceland under the Norwegian crown, ending the island’s commonwealth period.

Norwegian kings like Håkon Håkonsson (r. 1217–1263) presided over a relatively stable kingdom and negotiated with Scottish and English kings over control of the Hebrides and the Isle of Man. The Treaty of Perth in 1266 ceded the Hebrides to Scotland in return for payment, a sign that Norwegian influence in the western seas was ebbing.

Norway’s role matters because it kept Scandinavia connected to the Atlantic world, even as the main thrust of expansion turned toward the Baltic.

3. Swedish magnates and the eastward push

Sweden’s rise was slower and more fractured, but by the mid-13th century, figures like Birger Jarl were consolidating power. Birger, who effectively ruled Sweden in the 1240s–1260s, is associated with campaigns into Finland. The exact dates and details are debated, but Swedish influence in Finland grew in this period, often framed as crusades against pagan Finnic groups.

Swedish nobles and bishops built castles and churches along the Finnish coast and river routes. Over time, this created a Swedish-Finnish realm that would be important in later medieval and early modern wars with Novgorod and Muscovy.

This matters because it shows Sweden, often seen as the late bloomer of the three, carving out its own eastern sphere that would shape northern politics for centuries.

4. The church and the merchants

Behind the kings were quieter but powerful actors. The church, with archbishoprics in Lund (for Denmark and much of Scandinavia) and later Uppsala (for Sweden), tied the region to Rome and to broader church reforms. Monasteries like Cistercian houses brought in new agricultural techniques and helped clear land.

Merchants, especially German ones, turned Baltic trade into big business. The rise of the Hanseatic League in the 13th century, with key ports like Lübeck and Visby, meant that Scandinavian rulers had to negotiate with powerful trading cities. Grain, fish, timber, furs, and iron flowed out of the north, while cloth, salt, and luxury goods flowed in.

The church and merchants matter because they show how Scandinavian power in this period was not only about swords. It was also about integration into a wider economic and religious system that both empowered and constrained the kings.

What did this change: from fringe raiders to integrated kingdoms

By 1300, Scandinavia had changed in several ways that mattered for European history.

1. The Baltic became a contested core, not a backwater

Scandinavian and German expansion turned the Baltic from a loose contact zone into a dense web of Christian polities, trading cities, and crusader states. Denmark in Estonia, Sweden in Finland, the Teutonic Order in Prussia and Livonia, and German merchants in ports all around the sea created a new political and economic core.

This shift meant that future conflicts between Sweden, Denmark, Poland-Lithuania, and Russia would center on control of this sea. The High Middle Ages laid the groundwork for those later Baltic power struggles.

2. Early state-building in the north

The consolidation of law codes, royal councils, and church structures in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden created more durable states. They were still fragile and prone to civil war, but they had recognizable institutions, from royal chancelleries to regional assemblies (things/ting).

These institutions made later experiments like the Kalmar Union possible. In 1397, long after our period, the three crowns were united under a single monarch. That union rested on the shared political culture and church structures that had grown during the High Middle Ages.

3. A shift in identity and reputation

To their southern neighbors, the Scandinavians of 1200 were no longer the terrifying pagans of 900. They were Christian rulers, sometimes allies, sometimes rivals, often borrowers of legal and cultural fashions from Germany and England. They sent pilgrims to Rome and Jerusalem, joined crusades, and married into European dynasties.

Inside Scandinavia, sagas and chronicles began to memorialize the Viking past. Icelandic writers in the 12th–13th centuries, living under Norwegian influence, wrote the sagas that shape modern images of Vikings. The Viking Age became a remembered heroic era, not a current way of life.

These changes matter because they show that Scandinavia did not “drop out” of European history. It changed its role, from outsider raiders to insider participants in the same political and religious game as everyone else.

Why it still matters: fixing the “they vanished after Vikings” myth

The Reddit instinct is common: once the longships stop hitting English monasteries, Scandinavia seems to fade from the story. That is mostly a problem with which sources get attention.

English and French chronicles, which drive many popular narratives, had less reason to talk about Scandinavia after 1100. The action for them was the Norman kings, the Capetians, the Crusades in the Levant. Meanwhile, a lot of Scandinavian energy went east and inward, into the Baltic and into state-building, which those chroniclers cared less about.

From a Baltic or northern European perspective, though, Scandinavia stayed relevant. Danish kings were major players in northern Germany. Swedish and German crusaders reshaped the eastern Baltic. Norwegian control of the North Atlantic linked Europe to Icelandic literary culture and to the last European outposts in Greenland.

Understanding Scandinavia in the High Middle Ages corrects two myths at once. It shows that Vikings did not just “stop,” they were absorbed into new Christian kingdoms. It also shows that medieval Europe was not just France, England, and the Holy Roman Empire. The north mattered, especially for the Baltic world that would later become a major arena of early modern warfare and trade.

So no, the Norse did not simply “squabble, do a little crusade, and fade out.” They swapped axes for law codes, raiding for crusading, and dragon ships for cogs on the Baltic. The tools changed, the ambitions did not.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Scandinavia remain important after the Viking Age?

Yes. After the Viking Age, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden became Christian kingdoms that stayed influential in Baltic trade, crusades, and regional politics. They shifted from raiding in the Atlantic to building states and expanding into the Baltic region.

What were the Northern Crusades and how was Scandinavia involved?

The Northern Crusades were campaigns from the late 12th century aimed at converting and conquering pagan groups around the eastern Baltic, such as Finns, Livonians, and Estonians. Danish and Swedish rulers joined these crusades, seizing territory in Estonia and Finland and expanding their influence eastward.

How did Christianity change medieval Scandinavia?

Christianity tied Scandinavia to the wider Latin Christian world. It brought bishops, monasteries, and literacy, which helped kings centralize power, issue law codes, and claim divine authority. This shift turned loose Viking-era chieftaincies into more stable Christian monarchies.

Why does Scandinavia seem to disappear from medieval history after 1100?

Many popular histories rely on English and French sources, which focused less on Scandinavia after Viking raids stopped. Scandinavian politics and expansion moved toward the Baltic and internal consolidation, areas those chroniclers cared less about. From a Baltic perspective, Scandinavia remained a major regional power.