President Andrew Johnson succeeded President Abraham Lincoln upon his death in 1865. Johnson was Lincoln’s Vice President. In 1868, Johnson was impeached by the House of Representatives. The reason for impeachment was his “high crimes and misdemeanors,” primarily for violating the Tenure of Office Act Congress had passed the year before. He had removed his Secretary of War, Edwin McMasters Stanton and tried to replace him with Brevet Major General Lorenzo Thomas. Johnson was the first President to be successfully impeached, though he was later acquitted by the Senate.

Shortly after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination and Andrew Johnson became president, there had been high tensions between the executive branch and legislative branch. While Lincoln was in favor of a more moderate reconstruction after the Civil War, Johnson did not. The Radical Republicans had been very much against Lincoln, but he had been popular in the North, making it so the Radical Republicans were deprived of the political power they needed.

The Radical Republicans had hopes that Johnson would be able to pass their policies for Reconstruction that gave newly freed slaves protection and punished former slave owners and government and military officials. But Johnson unexpectedly turned around and rejected them. After only six weeks of office, Johnson was offering amnesty for many of the former confederates, abandoning his original stricter policies. He vetoed the legislation that would extend former slaves’ civil rights and financial support. A few of his vetoes were overridden by Congress, which made way for confrontation between Johnson and Congress.

On a speaking tour around the Northern United States in August and September of 1868, Johnson destroyed his own political support. This tour became known as the Swing Around the Circle. Intending to establish a coalition of voters in support of Johnson due to the upcoming midterm elections, it instead ruined his reputation. His undisciplined and malicious speeches along with confrontations with hecklers that did not go well was known all around the country. Johnson had hoped that with the midterm elections, the Congress would be ruled by a Republican majority. But instead, the Radical Republicans passed civil rights legislation and took control over the president on Reconstruction and turned the Confederacy into five military districts.

Congress was unable to take full control over the military’s Reconstruction policy because, as president, Johnson was in command of it. Lincoln’s Secretary of War, who was now also Johnson’s, Edwin M. Stanton, was a Radical Republican himself. Stanton would follow any Congressional Reconstruction policies for as long as he was office. Congress worried that Stanton would be replaced, so they passed the Tenure of Office Act in 1867. Even with Johnson’s veto, Congress was able to override him. The Tenure of Office Act made it so that before dismissing any Cabinet members, the President was to seek advice and consent from the Senate. The act was written with Stanton in mind specifically so Johnson could not dismiss him.

However, the act did give Johnson the right to suspend officials and Cabinet members when Congress was not in session. After Stanton refused to resign, Johnson suspended the Secretary of War on August 5, 1867. He appointed General Ulysses S. Grant, who was the Commanding General of the Army, as Secretary of War ad interim (which means “in the meantime” or “temporarily”). Johnson later on disagreed with Grant from an understanding they had. The President claimed that if the Senate failed to comply with his removing of Stanton, that Grant would remain in office or notify the Johnson before hand if he were to resign. Johnson planned on making a court case to test the Tenure Act’s constitutionality. Later, Grant disagreed that they had never made an agreement like this.

With a vote of 35-to-6, the Senate passed a resolution on January 7, 1868 that disagreed with Stanton’s removal. That same day, Grant vacated his office when he wrote his resignation letter, though he did not tell Johnson. Stanton took back his office. The following day, Grant, trying to give Johnson a reason for not pre-notifying him, gave the President stammering and unintelligible excuses. Johnson believed the Tenure of Office Act was unconstitutional, so until January 28, he ignored Stanton’s reinstatement. On the twenty-eighth of January, he offered brevet major general Lorenzo Thomas the position of Secretary of War. Originally, Thomas turned the offer down because he wanted to remain Adjutant General until he retired. Later on, he was able to convince Thomas to assist him in making a test case.

Lorenzo Thomas was appointed to the position of Secretary of War on February 21, 1868. Stanton was, at once, ordered to be removed from office. Thomas himself delivered the dismissal notice to Stanton. Stanton, however, refused to accept it and built a barricade around his office. He then ordered for Thomas’s arrest for violating the Tenure of Office Act. To tell the President he had been arrested, Thomas requested he be taken to the White House. But Stanton decided to drop the charges upon realizing that with Thomas’s arrest, the courts would then be permitted to review the law. Stanton claimed afterwards that Johnson, by removing a cabinet member without the Senate’s approval, was breaking the Tenure of Office Act. From there on, the problem escalated and became known around the country. Representative William D. Kelley, the following day, ordered that Andrew Johnson needed to be punished.

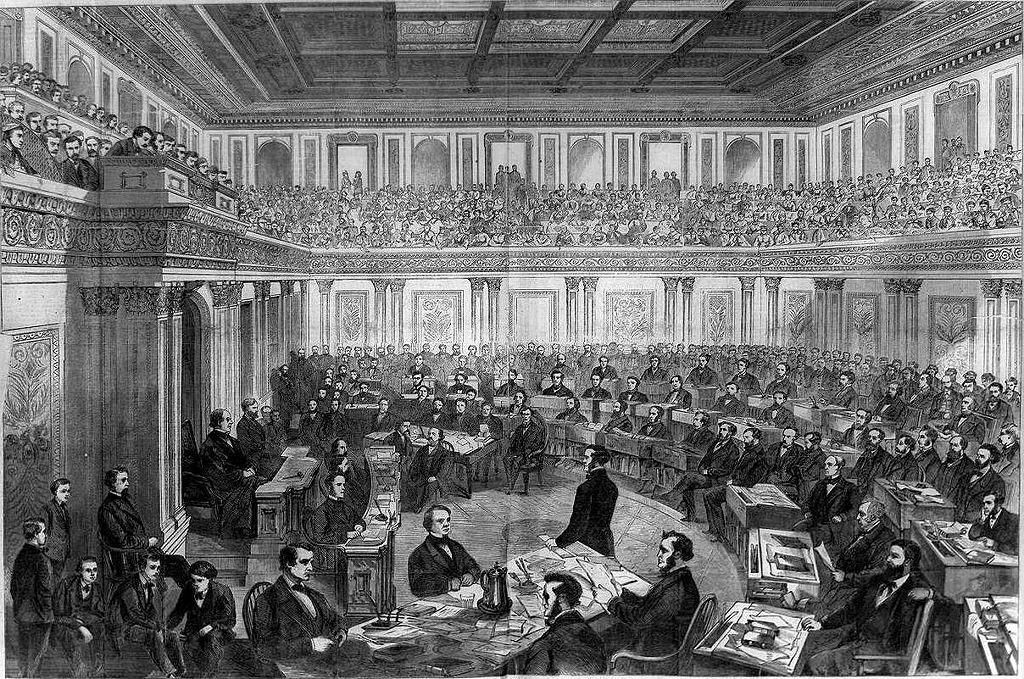

Only three days after Stanton’s dismissal, the House voted in favor of a resolution to impeach President Andrew Johnson on February 24, 1868 in a 126-to-47 vote. The reason for impeachment was high crimes and misdemeanors. Thaddeus Steven and John A. Bingham were the two sponsors of the resolution. Immediately, they were dispatched to tell the Senate that they had voted for impeachment. A week later, eleven articles of impeachment were adopted by the Senate against Johnson. You can read the full articles here. Among them, Johnson was accused of violating the Tenure of Office act and for conspiracy.

Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase presided over the trial, which started in the Senate. Committees were organized for representation of the prosecution and defense. John A. Bingham, George S. Boutwell, Benjamin F. Butler, John A. Logan, Thaddeus Stevens, Thomas Williams, and James F. Wilson made up the impeachment committee. On the opposing side, Jeremiah S. Black (who resigned before the start of the trial), Benjamin R. Curtis, William M. Evarts, Alexander Morgan, Thomas A. R. Nelson, and Henry Stanbery were on the defense team. On March 13, 1868, the trial officially began.

It was ruled by Chief Justice Chase, a Radical Republican, that Johnson should be able to present evidence that by appointing Thomas to his cabinet, he had been intending to provide a test case to challenge the Tenure of Office Act’s constitutionality. Chase was overruled by a majority vote.

Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio attempted to add two Radical members to the senate before the start of the trial. He tried to gain Colorado’s admission as a state. Wade was unable to gain two-thirds majority vote to override the anticipated veto from Johnson. However, his attempts failed. Another attempt was made shortly before the verdict vote was scheduled to take place to admit senators from certain Reconstruction states so that there would be more reliable Radical members. This was another unsuccessful attempt.

Johnson’s defense committee requested forty days on the first day of the trial to collect and provide evidence and witness because the prosecution had been given more time to do so. Instead of forty days, they were only granted ten days. On March 23, the proceedings began. Because not all states were represented in the Senate, Senator Garrett Davis argued, the trial could not be held and should instead be adjourned. This motion was voted against.

Once the charges against President Johnson were made, Henry Stanberry asked for an additional forty days to gather evidence and to summon witnesses. His argument was that there was not nearly enough time to prepare johnson’s reply with only ten days. Meanwhile, John A. Logan argued that they should start the trial at once. He said that Stanberry was only stalling to give them more time. In a 41-to-12 vote, Stanberry’s request was turned down. The next day, the Senate voted for six more days to be granted to the defense to prepare evidence.

On March 30, the trial commenced yet again. With a three-hour long speech about historical impeachment trials that dated back to King John of England (who ruled from 1166-1216), Benjamin F. Butler opened for the prosecution. Butler continued speaking out against Johnson for days and how he violated the Tenure of Office Act. Further, he also argued that Johnson had issued Army officers direct orders without sending them through General Grant first. The defense argued that the president had not been in violation of the Tenure of Office Act because Stanton had not been reappointed as Secretary of War at the start of Lincoln’s second term. Therefor, Stanton had just been a leftover appointment from Lincoln’s 1860 cabinet and he was not protected by the Tenure of Office Act. Several witnesses were called into court by the prosecution up until they rested the case on April 9th.

Benjamin R. Curtis brought it to attention that the Senate had amended the Tenure of Office Act after the House had passed it, meaning that to resolve the differences, it had to be returned to a Senate-House conference committee. Curtis quoted the minutes of these meetings and revealed that no notes about it had been made by House members. Their main purpose had been to keep Stanton in office, while the Senate disagreed. The first witness of the defense, Lorenzo Thomas, was then called. Thomas did not prove the acceptable information in the defense’s cause. Butler attempted to his Thomas’s information to the advantage of the prosecution. General William T. Sherman, the next witness, testified that Johnson had offered to appoint him to succeed Stanton to ensure that the department was administered effectively. This testimony damaged the prosecution, as they had been expecting for Sherman to testify that Johnson had offered to appoint him to obstruct the operation of the government, along with the overthrow. Sherman affirmed that the only reason Johnson wanted him as Secretary of War was to not execute directions to the military that would contradict the will of Congress. The House ended up voting 126-to-47 in favor of Johnson’s impeachment.

Fifty-four members represented the, at the time, twenty-seven states, whose legislatures were able to elect Senators, in the Senate. Two-thirds vote was required to remove Johnson from office, so thirty-six. They voted three times in the Senate, each with 35 Senators that voted guilty and 19 not-guilty, meaning they were one vote shy of impeaching Johnson. Thus, President Johnson was acquitted.

Senators William Pitt Fessenden of Maine, Joseph S. Fowler of Tennessee, James W. Grimes of Iowa, John B. Henderson of Missouri, Lyman Trumbull of Illinois, Edmund G. Ross of Kansas, and Peter G. Van Winkle of West Virginia were all concerned that the proceedings had been manipulated so there was a one-sided presentation of evidence. These Republican Senators defied their party and voted not-guilty. Before they had taken the first vote, senior senator from Kansas Samuel Pomeroy told the junior senator from Kansas Edmund Ross that if he voted for acquittal, Ross would be subject, due to bribery, of investigation.

On May 16, 1868, the first vote was taken in the Senate for the eleventh articles with a result of 35-to-19. The Senate had adjourned for ten days to take another vote on May 26 on the other articles in hopes of manipulating the seven Republican senators who had voted for acquittal. Meanwhile, the House made a resolution to investigate the “improper or corrupt means used to influence the determination of the Senate”, a resolution that Butler had led. Even with all the pressure, the seven Republicans did not change their acquitting votes. On May 26, the trial results were the same, 35-to-19. Butler conducted hearings on the widespread results that these Republican senators had voted for johnson’s acquittal due to bribery. throughout Butler’s and others’ hearings, there was more and more evidence that some of these seven acquittal votes had been from promises of patronage jobs and cash cards. The investigations never ended in any charges against anyone.

There is evidence, however, that the prosecution had made attempts to bribe these seven senators to switch their votes to conviction. Senator Fessenden from Maine was offered Ministership to Great Britain, but he kept his vote. It was then discovered that Senator Pomeroy from Kansas had written a letter seeking $40,000 as a bribe from Johnson’s Postmaster General for Pomeroy’s acquittal vote along with a few others. Pomeroy, in the end, voted for conviction. Benjamin Wade told Benjamin Butler that he would appoint him as Secretary of State when Wade was to become President if Johnson was convicted.

After their terms ended, none of the Republican senators that had voted for acquittal ever held political elective office again. They had been under immense pressure to change their votes during the trial, but not one of them changed their votes in the three trials held.