Lucretia Mott was a leading abolitionist and feminist before, during, and after the American Civil War. In 1833, Mott took part in establishing the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society and helped to write the Declaration of Sentiments during the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention.

On January 3, 1793, Lucretia Coffin was born in Nantucket, Massachusetts to Thomas and Anna Folger Coffin. Lucretia was the second of her parent’s eight children and grew up in a Quaker family. Thirteen-year-old Coffin was sent to the Nine Partners School located in Millbrook, Dutchess County, New York in 1806. It was a Quaker school the Society of Friends ran. Coffin continued her education there for three years before working as a teacher at the school. While working as a teacher, Coffin’s interest in women’s rights formed because male teachers were paid more than three times the amount as female teachers.

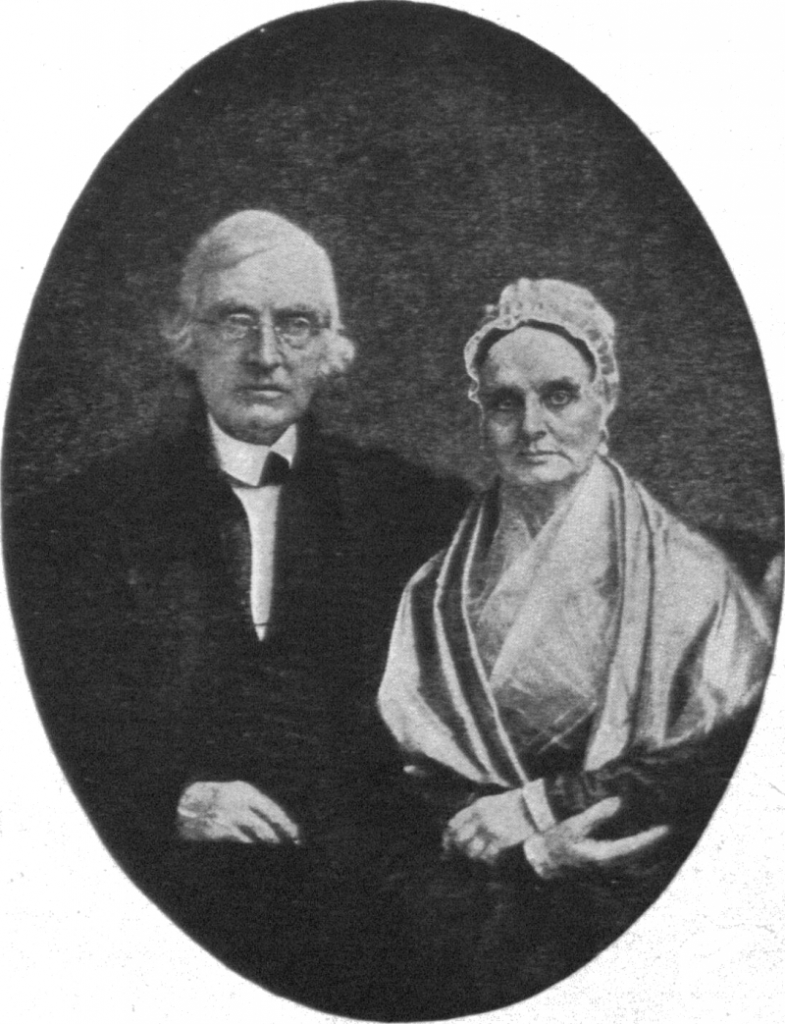

Coffin’s family moved up to Philadelphia a few years later. A fellow teacher at the Nine Partners School, James Mott, followed suit. On April 10, 1811, eighteen year old Coffin married James Mott. The couple would go on to have six children. Five of their children survived childhood and would all go onto to follow their parents and become abolitionists and members of other reform movements.

Growing up, Mott had always found slavery to be evil, like most Quakers. Many of them even refused to use cotton, sugar, and any other goods produced by slaves. Mott became a Quaker minister in 1821, and traveled extensively with her husband to perform sermons, many even included her views on slavery. James Mott helped to establish the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1833. During the first meeting in Philadelphia, Lucretia Mott was the only woman to speak. She then, with many other abolitionist women, founded the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. The society included many black women as well, and they not only spoke out against slavery, but also racism. While working hard as an abolitionist, Mott continued to manage her home and housed many refugee slaves in need of a place to sleep. She was praised by many for this, and also organized anti-slavery fairs with fellow female abolitionists.

Mott attended the 1837, 1838, and 1839 Anti-Slavery Conventions of American Women. The third convention was held near Mott’s home in Philadelphia. A mob broke in and destroyed the building, and tried to chase down black female abolitionists. Mott and many other women in attendance notably linked arms to run out of the building safely. The mob tried to target the Mott household and any place where blacks were staying, and Mott awaited the mob in her parlor while the other women were redirected to safety.

The following year in June, Mott was one of six female delegates who attended the General Anti-Slavery Convention in London, England. Most of the men were against female attendance, and voted for them to sit in a segregated area during meetings. While many men did not want any women attending, some of the most notable speakers and delegates spoke out against this and sat with the women in the enclosed area. During the convention, Mott befriended Elizabeth Cady Stanton, a female rights activist and abolitionist. The two would stay friends for the rest of Mott’s life, and she served as a mentor to Stanton.

After returning to the U.S., Mott often attended lectures and made her own speeches. She was determined for the anti-slavery cause to become what it was elsewhere around the world. Mott traveled around the U.S. for lectures in cities such as New York and Boston, even making her own speeches while in Baltimore, Maryland, and Virginia. Her and slave owners would meet often so she could discuss the abolitionist cause with them, and made a speech in D.C. when Congress returned, with over forty Congressmen in attendance. John Tyler, the tenth president, was quite impressed when Mott made a speech with him in the audience.

With Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mott organized the first U.S. public women’s right’s convention, The Seneca Falls Convention, in Seneca Falls, New York in 1848. While she and Stanton did not necessarily agree on everything, they both agreed women deserved the same rights as men. The Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments was signed and partially written by Mott, though mainly written by Stanton. Mott continued to mentor and be an inspiration for Stanton as she fought for women’s suffrage. Martha Coffin Wright, Mott’s sister, was also a women’s rights activist.

In a time where divorce was difficult and men almost always had custody of their children, Mott held strong beliefs that women should have custody of their children and divorce should be easier for them. Many feminists disagreed with her at first, thinking this to be scandalous. Mott was not only an influential women’s rights activist and abolitionists, but she was also very influential among Quakers. In 1864, she helped establish Swarthmore College, a coeducational Quaker school.

Mott was elected the American Equal Rights Association’s first president following the civil war, and held this position for two years until her resignation in 1868. Stanton and Susan B. Anthony had found an ally in George Francis Train, who supported women’s suffrage but believed black men should not be permitted to vote. Many key members went through a falling out because of it, and Mott tried to fix the damage and reconcile Stanton, Anthony, and Lucy Stone, an important member of their organization.

However, Mott was beginning to suffer through bad health and had stomach disorders. She powered through her illnesses though, and continued her popular speeches and sermons. Mott continued to speak of women’s rights and suffrage, but was also a strong advocate for allowing blacks to vote and be given the same rights as white men. A hard worker, Mott had been apart of many abolitionist and women’s rights organizations throughout her life, and continued to be even as her health declined. Many people judged her widely on her views as well.

Lucretia Coffin Mott died on November 11, 1880 in her Pennsylvania home at eighty-seven years old due to pneumonia. At her bedside, were her living children and grandchildren. Her husband had previously died twelve years before in 1868. She was buried in North Philadelphia near her home at the Quaker Fairhill Burial Ground.