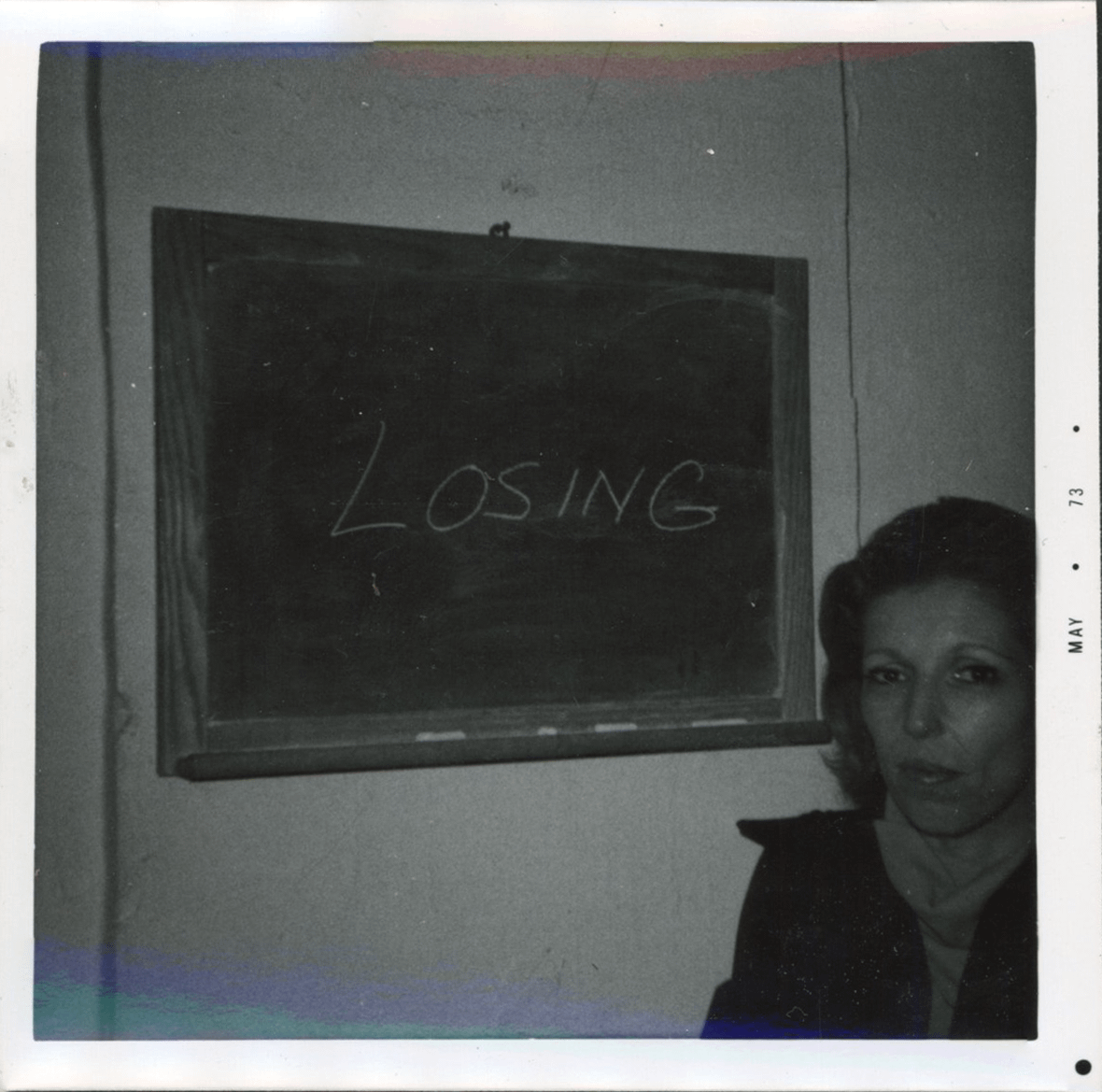

They sit in a loose row, hair set, skirts pressed, hands folded just so. Behind them, a blank studio wall. In front of them, a camera. The artist asks one question: “What’s your greatest fear?”

It is Long Island, 1973. The women have come in from the suburbs to a loft in SoHo, recruited through a local arts program called the Five Towns Music and Art Foundation. They think they are doing something cultured and respectable: an art project, a museum-adjacent activity. Instead, they are about to have their private anxieties turned into public art.

The resulting series, later shown at OK Harris Gallery, captured something that statistics and political speeches rarely did: what ordinary American women in the early 1970s actually feared. Not in theory, but in their bones.

These photographs of Long Island women answering “What’s your greatest fear?” sit at the crossroads of second-wave feminism, rising crime anxiety, and the strange new world of conceptual art. By tracing how and why this project happened, you can see what it meant to be a woman in suburban America at the height of the 1970s culture wars.

What was this 1973 Long Island “greatest fear” project?

The Reddit post that resurfaced this story is short and almost offhand. The poster, an artist, recalls that “back in the early ‘70s” they were doing a series of conceptual art projects using participants. They worked as a museum tour guide and met a group of women enrolled in art tours through the Five Towns Music and Art Foundation, a real community arts organization based in Nassau County, Long Island.

When the artist mentioned an ongoing project, the women were curious. They agreed to come into the city, to the artist’s loft, and sit for photographs. The concept was simple. The artist would ask each woman about her greatest fear and photograph her as part of that inquiry. The work was then shown at OK Harris Gallery in SoHo, one of the early commercial galleries in the neighborhood, founded by Ivan Karp in 1969 and known for conceptual and photo-based work.

Conceptual art in the early 1970s often treated language, ideas, and social situations as the artwork itself. Here, the “piece” was not just the photograph, but the encounter: middle-class Long Island women, a downtown loft, a question that cut through small talk. The art was the act of asking and answering, captured on film.

In simple terms, this was a conceptual photography project in which suburban women were photographed while participating in an interview about their greatest fear. The photographs documented both their appearance and the emotional weight of their answers.

So what? Because the project used ordinary women as subjects and their fears as content, it turned private anxieties into public evidence of what it meant to be female and suburban in 1973.

Why 1973 mattered for women’s fears

To understand what those women might have said, you have to sit inside 1973 for a minute.

On paper, it was a year of breakthroughs. The Supreme Court decided Roe v. Wade in January 1973, legalizing abortion nationwide. Title IX had passed the year before, promising equal opportunity in education. Ms. magazine was on newsstands. The Equal Rights Amendment had been approved by Congress in 1972 and was racing through state legislatures.

But the daily news was grim. Crime rates in New York City were climbing. Nationally, violent crime had roughly tripled since 1960. The Manson murders were only a few years in the past. The 1972 Central Park jogger case was still in the future, but stories of sexual assault and random violence were already part of the urban rumor mill.

For Long Island women, the suburbs were supposed to be the safe alternative. Levittown and its clones had been sold as havens from city crime and chaos. Yet by the early 1970s, suburban women were hearing about burglaries, domestic violence, and stranger danger. The “safe” world felt less solid.

At the same time, second-wave feminism was telling women to name their oppression. Consciousness-raising groups encouraged them to talk about rape, marital dissatisfaction, wage discrimination, and the fear of ending up with no identity beyond wife and mother.

So when a young artist in SoHo asked, “What’s your greatest fear?” those women were answering in a world where both the public conversation and the crime statistics were telling them they had a lot to be afraid of.

So what? Because 1973 sat at the collision of rising feminist awareness and rising crime anxiety, the fears those women voiced were shaped by both political change and personal vulnerability.

Who were these Long Island women, really?

The Five Towns Music and Art Foundation drew from a particular slice of Long Island. The “Five Towns” usually refers to the communities of Lawrence, Cedarhurst, Woodmere, Inwood, and Hewlett in Nassau County. In the postwar decades, this area was largely white, middle and upper-middle class, with a significant Jewish population and a growing professional class commuting into New York City.

Women who signed up for art tours in the early 1970s were not the most isolated homemakers. They were the ones who wanted culture, who had the time and money to attend museum programs. Many were likely college-educated, or at least comfortable in museum spaces. Some may have been teachers, social workers, or part-time professionals. Others were full-time homemakers with kids in school and a station wagon in the driveway.

They were not activists in the streets, but they were not apolitical either. They were reading newspapers, hearing about the ERA, watching Watergate unfold on television. They were navigating marriages in a decade when divorce rates were climbing and the old script of “marry young, stay forever” was starting to crack.

So their fears probably fell into a few broad categories, even if the exact words are lost:

• Fear of crime and physical harm. Rape, home invasion, being attacked in the city or even in their own homes.

• Fear of abandonment or divorce. Being left without financial security, especially if they had not worked for years.

• Fear for their children. Drugs, accidents, the draft (though Vietnam was winding down), or their kids rejecting the values they had built their lives around.

• Fear of purposelessness. Ending up “just a housewife” with no identity once the kids left, or realizing too late that they had given up their own ambitions.

• Fear of illness and aging. Cancer, mental breakdown, being institutionalized, becoming dependent.

In other words, their fears were not exotic. They were the same ones that filled advice columns and late-night kitchen conversations. The difference is that here, those fears were being treated as material for art.

So what? Because these women were relatively privileged yet deeply anxious, their participation reveals how even “successful” suburban lives were threaded with fear of loss, violence, and invisibility.

How conceptual art turned fear into a subject

By the early 1970s, SoHo was filling up with lofts, galleries, and artists experimenting with new forms. OK Harris Gallery, where the project was shown, was one of the first to take photo-based and conceptual work seriously in a commercial setting.

Conceptual artists often stripped art down to ideas and processes. A question could be the artwork. A list, a map, a set of instructions. In this case, the artist created a social situation: invite a specific group of women, ask them a personal question, document their presence and responses.

Photography made this legible to viewers. Even if the text of each woman’s fear was not displayed, her posture, clothing, age, and expression told a story. Were her hands clenched? Was she smiling tightly? Did she look straight at the camera or away?

At the same time, feminist artists were starting to use their own bodies and experiences as material. Judy Chicago was working on what would become “The Dinner Party.” Martha Rosler was making video and photomontage about domestic life and war. Adrian Piper was using her own presence in public spaces as a kind of social experiment.

This Long Island project fits that moment. It used real women, not models. It treated their fears as content worth recording. It blurred the line between documentary and art.

A conceptual art project is an artwork where the main focus is the idea or concept, not just the visual appearance. Here, the concept was that asking women about their greatest fear, and recording their responses, could reveal hidden truths about gender and society.

So what? Because the project framed ordinary women’s fears as worthy of gallery space, it helped shift who and what could be considered “proper” subjects for serious art.

What did these fears reveal about gender and power?

Even without a transcript, we can read the likely pattern: women’s fears in 1973 were not just about random misfortune. They were about power.

Fear of rape or assault was fear of male violence and a legal system that often blamed victims. Marital fears were about economic dependence in a world where many women could not easily support themselves. Fear of purposelessness was about a culture that defined women by their relationships to others, not their own work or ideas.

Suburban Long Island added another layer. These women lived in houses that were supposed to be safe, but their safety depended on husbands’ incomes, police protection, and social norms that could turn on them if they stepped out of line. A woman who left a bad marriage risked social ostracism. A woman who reported domestic abuse risked not being believed.

So when they sat in that SoHo loft and answered the artist’s question, they were doing something slightly radical: saying the quiet part out loud. Naming fear is a way of admitting that the system you live in does not fully protect you.

There is a clean causal claim here. When women in the 1970s began publicly naming their fears of violence, abandonment, and invisibility, they helped fuel legal and cultural changes around domestic abuse, rape law, and women’s economic rights.

So what? Because these fears were rooted in structural inequality, not just personal neuroses, making them visible helped push the conversation toward changing laws and expectations rather than just telling women to “calm down.”

From gallery wall to Reddit thread: the afterlife of a project

In 1973, the show at OK Harris would have been seen by a relatively small audience: downtown art people, a few critics, maybe some of the women and their families if they made the trip in. Then the prints went into storage, or into a box, or onto a shelf.

Decades passed. Long Island changed. The Five Towns saw demographic shifts. The women in the photographs aged, retired, or died. Their children moved away. The fears they named in their thirties or forties played out in real time.

Then, sometime in the 21st century, the artist scanned the images and posted them online. Reddit’s r/TheWayWeWere, a community dedicated to historical photos and memories, picked them up. The title was simple: “What’s your greatest fear? Long Island women respond (1973).” The post pulled in more than 15,000 upvotes and hundreds of comments.

Why did it hit a nerve? Partly, nostalgia. The hair, the clothes, the grain of the film. But the real hook was the question. Viewers in 2020s America have their own list of fears: climate change, mass shootings, political collapse. Looking at these women, they wanted to know: what were you afraid of, and did it come true?

People often assume the 1950s and early 1960s were safe and simple, and that fear is a modern condition. Projects like this cut through that myth. They show that even in the “good old days,” women were quietly terrified of things that had no easy fix.

So what? Because the project resurfaced in a digital age, it now functions as both historical document and mirror, letting new generations compare their own fears to those of women who lived half a century ago.

What this small project tells us about the 1970s

This was not a famous exhibition. It did not rewrite art history or policy. But it is a sharp little window into a specific time and place.

It shows how conceptual art escaped the academy and the avant-garde and started involving regular people. It shows how suburban women, often written off as apolitical or complacent, were thinking hard about risk, safety, and meaning. It shows how the 1970s were not just about big headlines like Roe v. Wade, but about quieter questions asked in lofts and living rooms.

Most of all, it reminds us that fear is historical. What people fear, and what they feel allowed to say they fear, changes over time. In 1973, Long Island women were beginning to speak more openly about violence, divorce, and selfhood. An artist with a camera gave them one more place to do it.

So what? Because this modest art project captured the emotional undercurrent of a generation of women, it helps explain why the 1970s produced such intense debates over gender, safety, and the meaning of a “good life.”

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the 1973 Long Island women “greatest fear” project?

It was a conceptual photography project in which an artist invited suburban Long Island women, recruited through the Five Towns Music and Art Foundation, to a SoHo loft and asked each of them about her greatest fear. The women were photographed as part of this process, and the resulting images were exhibited at OK Harris Gallery in 1973.

Who organized the Long Island women fear photos shown on Reddit?

The Reddit post was made by the original artist, who in the early 1970s worked as a museum tour guide and used participants from the Five Towns Music and Art Foundation’s art tour program. The artist has not given a full name in the Reddit snippet, but did state that the work was shown at OK Harris Gallery in SoHo.

What did women in the early 1970s fear most?

Evidence from projects like this, along with feminist writing of the time, suggests that many women in the early 1970s feared rape and physical assault, abandonment or divorce without financial security, loss or harm to their children, and a life without personal identity beyond wife and mother. These fears reflected both rising crime rates and the growing awareness of gender inequality.

Why are the 1973 Long Island fear photos important today?

They matter because they capture ordinary women at a moment when second-wave feminism, rising crime anxiety, and changing family structures were reshaping American life. The project turns their private fears into a public record, allowing later generations to see how gender, safety, and identity were experienced in real time, not just in laws and headlines.