The Siege of Yorktown unofficially marked the end of the Revolutionary War, though a treaty between Britain and America was not signed until later. When the treaty was adopted on September 3, 1783, it was officially over, nearly two years after the decisive Battle of Yorktown.

Following the battle, Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette had hoped to lead expeditions to the port cities still under British control. General George Washington, close friend of Lafayette’s, disagreed. He believed it would be much more useful if the Frenchman was to return to France to gain more naval support. At the same time, Congress also appointed him as the advisor to Benjamin Franklin in Paris, John Jay in Madrid, and John Adams in The Hague, the three current American envoys. That was not all Congress did though. They also sent, on behalf of Lafayette, an official commendation letter to King Louis XVI.

On December 18, 1781, Lafayette left America, not to return again until 1784. During his time in the war, he had formed many unlikely friendships and became recognized as a revolutionary hero in both America and his home country of France. Most notably though, Lafayette befriended George Washington and also formed a trio with John Laurens, who ended up dying after Yorktown at the Battle of Combahee River on August 27, 1782, and Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton would later go on to become the first Treasury Secretary of the U.S. While Washington could not speak French, both Hamilton and Laurens were bilingual. Hamilton’s letters to both of the young men expressed their close relationship, and possibly even suggested a homosexual relationship that most disagree on. Either way, Lafayette became especially close with both Hamilton and Laurens and also George Washington, among others.

Lafayette arrived home in Paris on December 18, 1781 to his wife, Adrienne de La Fayette, and two children, Anastasie and Georges Washington de Lafayette. He was received at Versailles the next month on January 22, 1782, welcomed home as a hero for his incredible chivalry during the American Revolution. Shortly after, the happily married Lafayettes welcomed their daughter Marie Antoinette Virginie, a name that had been recommended to him by Thomas Jefferson.

When promoted to a maréchal de camp, Lafayette skipped over many military ranks. That same year he was made an Order of Saint Louis Knight and assisted in preparations for an expedition against the British West Indies with his country and Spain. But when the Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783, officially marking the end of the Revolutionary War, the expedition was made no longer necessary.

Future first American Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson, began to collaborate with Lafayette on establishing a trade agreement between their two countries. At the time, the U.S. was in great debt to France, one of the reasons for the negotiations. Lafayette soon joined the Society of the Friends of Blacks, a French group that advocated rights for blacks and the end of the infamous slave trade. Still very close with Washington, the Frenchman wrote to him of emancipating his slaves and instead having tenant farms. Washington was the owner of over 300 slaves though. He did express interest in Lafayette’s plans, but ultimately declined the offer. Lafayette did not entirely give up on this plan though, and purchased a piece of land to hopefully start a plantation with tenant farmers in French Guiana.

Two and a half years after his departure from America, Lafayette returned in 1784. Upon his arrival he was enthusiastically greeted by Americans. Leaving out Georgia, he toured through twelve of the thirteen states. On August 17, 1784, the Frenchman visited his friend Washington at his Virginia plantation, Mount Vernon. Ever the abolitionist, Lafayette continued to urge him to free his slaves, but Washington refused. Lafayette also tried to convince the legislature in Pennsylvania to form a new federal union, unlike that created in the Articles of Confederation which were in use from 1781 to 1879. He also took part in peace negotiations in Mohawk Valley, New York with the Iroquois people. When he visited Maryland, it became the first state to honor him and all male heirs as natural born citizens of Maryland. Maryland was not the only state to do so; Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Virginia all granted him the same honor. Once the Constitution was ratified in 1789, this made him a natural born United States citizen, something he boasted about later in life because French citizenship had yet to exist. Lafayette was also gifted with an honorary Harvard degree, a bust from Virginia, and a portrait of George Washington from Boston.

Over the next few years, Lafayette turned the Hôtel de La Fayette located in Paris, his house, into the American headquarters in France. Every Monday, Lafayette would host and dine with John and Abigail Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and John and Sarah Jay. Often times, more liberal French nobility would join them as well. He did not stop his work with Franklin and his successor, Thomas Jefferson, in lowering French and American trade barriers, and also worked with the two of them to seek treaties with other European countries of amity and commerce. Since the revocation Edict of Nantes had taken place more than a hundred years before, Lafayette also worked to put an end to the injustices faced and endured by French Protestants.

France was in a terrible fiscal state after the American Revolution, primarily because they had assisted the Americans in the war. King Louis XVI, in response to the crisis, called together an Assembly of Notables on December 29, 1786 with Lafayette appointed to the body. On February 22, 1787, not quite two months later, the assembly convened. Lafayette made many speeches advocating reform. He addressed how he decried people with close connections to the French court who had benefited from land purchases made by the government before hand. Lafayette called for an assembly that represented not just an assembly of French nobility and high ranking officials, but all French citizens. King Louis XVI however, decided to summon an Estate General that was to convene a couple years later in 1789. And of course, Lafayette was elected to the assembly, representing nobility from Riom, or the Second Estate. The Three Estates were made up of the clergy, nobility, and commons, which was much larger yet usually outvoted by the system used.

On May 5, 1789, the Estates General convened for the first time since an assembly in 1614. Right away, representatives debated on whether or not they should vote by head or Estate. If they voted by head then that would mean the Third Estate (commons), which was much larger, would dominate in voting, but if by Estate, then it would be much easier for the commons to be outvoted by the clergy and nobility. Lafayette, a member of the “Committee of Thirty”, declared they should not vote by estate and instead by head. Though most of the members of the Second Estate did not agree, the First Estate (clergy) was willing to join together with the commons. On May 17, 1789, it was declared the National Assembly by the Committee. Loyalists responded by saying that the group, including Lafayette, should be locked out. Those who had not been in support of the assembly would then meet inside. Until there was a constitution established, the members of the assembly who had been excluded refused to separate. This action became known as the Tennis Court Oath. The assembly continued their meetings though. On July 11, 1989, the draft of the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen” was presented to the assembly by Lafayette. Working with Thomas Jefferson, Lafayette had written the declaration, drawing ideas from The Virginia Declaration of Rights and Thomas Jefferson’s drafts of the American Declaration of Independence. Jacques Necker, the French Finance Minister, was dismissed from the assembly the following day due to being seen as a reformer.

Prominent lawyer, politician, and journalist Camille Desmoulins led an angry armed mob shortly after the dismissal. To protect the city, King Louis had the duc de Broglie lead the royal army to surround Paris. Then, the infamous Storming of the Bastille occurred on July 14, 1789 when the mob stormed the Bastille, a medieval political prison also used as a fortress and armory. This signified the beginning of the French Revolution of which Lafayette would play his own part in.

The day after the Storming of the Bastille, Lafayette became the commander in chief of the National Guard of France. An armed force, the National Guard had been established to maintain order in France under the Assembly’s control. Lafayette had been the one to propose both the Guard’s name and symbol, which was a cockade in the colors of the city of Paris—blue and red—and the royal shade of white. This would eventually come to be known as the French tricolor, the colors of the French flag adopted in 1794. Lafayette, as the head of the new National Guard, faced many difficulties and hardships. Many commoners held beliefs that Lafayette was assisting King Louis in keeping his power as the head of the Guard, while the king and loyalists felt as if Lafayette was no better than any revolutionaries. Then, on August 26, 1789, Lafayette’s declaration he had introduced a few months before was approved by the National Constituent Assembly. King Louis XVI ended up rejecting the declaration on October 2, 1789.

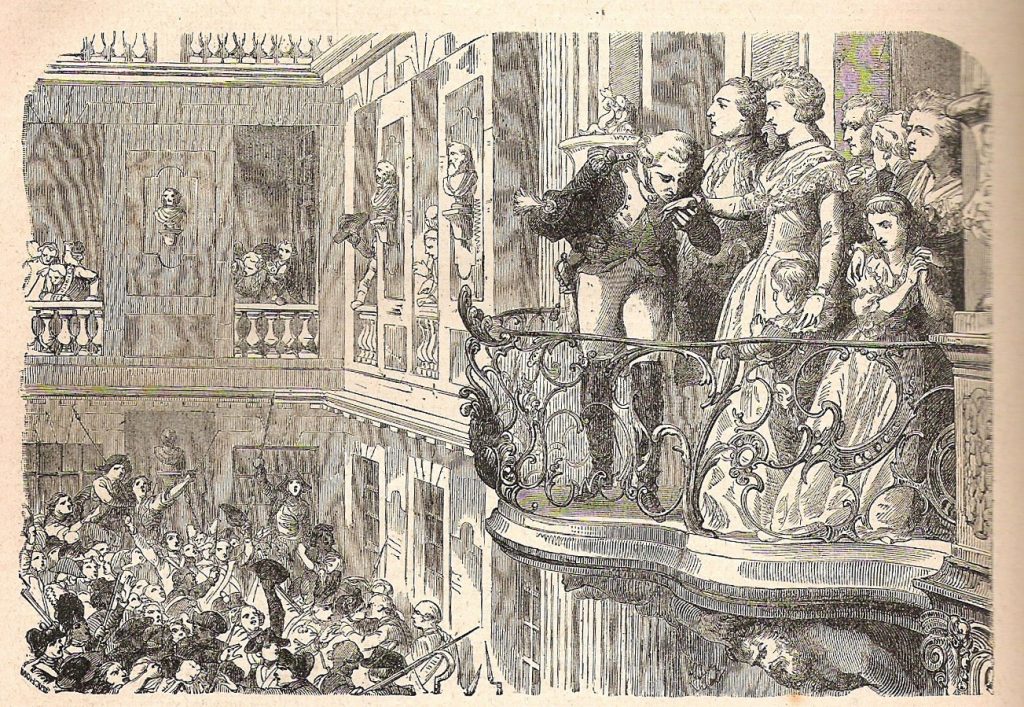

A crowd made up mostly of Parisian women fishmongers marched to Versailles on October 5, 1789, responding to famine and scarcity of bread, mainly. The Women’s March on Versailles, or just the March on Versailles, became knowns as one of the earliest yet most significant events to occur during the French Revolution. Lafayette reluctantly led the members of the guard to follow the march. The King finally accepted that the assembly had voted on the declaration during the march while he was at Versailles. Although, he did not accept requests to go to Paris. The crowd finally broke into the palace at dawn. In attempts to restore order amongst the people, Lafayette led the royal family onto the balcony of the palace. The crowd persisted that the king move to the Tuileries Palace in Paris and take his family with him. As soon as the king appeared at the balcony, the crowd broke into a chant. Marie Antoinette, the queen who was very unpopular, made an appearance at the balcony accompanying her children. She was ordered to get the children inside to safety. As soon as she came back out on the balcony, the crowd yelled to shoot her, but no one even made an attempt. Lafayette got the crowd cheering when he simply kissed the queen’s hand that day on the balcony.

While the radicals were only gaining more and more influence in France, Lafayette tried as hard as he could to maintain order as the leader of the National Guard. The mayor of Paris, Jean Sylvain Bailly, accompanied Lafayette in instituting a political club on May 12, 1790. The club was called the Society of 1789 and aimed at providing both balance and influence to radical Jacobins. Lafayette took the civic oath on the Champ de Mars on July 14, 1790 at what became known as the Fête de la Fédération.

He vowed to be faithful to his country and the king while holding up the constitution accepted by the King and National Assembly. Lafayette was the leader of the oath that day, taken by himself and his troops along with the king. To honor the french Revolution, it became a major holiday and festival in not just Paris, but all of France.

Lafayette did not cease to work on restoring order in his country over the course of the following months. He departed Tuileries to deal with conflict going on in Vincennes along with some members of the Guard on February 28, 1791. When Lafayette departed the palace, hundred of armed men arrived to help defend the king and his family at Tuileries. Rumours spread that these noble men had actually come to take King Louis away instead of defending him and that they would then put him at the head of a counter-revolution. As soon as he heard of this, Lafayette raced back to Tuileries. He was able to disarm the nobles after facing them in a brief standoff. Lafayette’s only became more popular with the French people because of his quick thinking and actions to keep the king protected at all times. This event later became known as the Day of the Daggers. But the royal family only became more and more imprisoned at the palace. The National Guard went against Lafayette’s orders on April 18, 1791 and prevented the king from leaving Tuileries to Saint-Cloud to attend a Maas.

King Louis XVI nearly escaped France on June 20, 1791 because of a plot called the Flight to Varennes. During this time, Lafayette was responsible for the custody of the royal family as the National Guard’s leader. Maximilien Robespierre accused Lafayette as a traitor for the royal family’s near escape. Many extremists blames him, such as Georges Danton. Because of these many accusations, the people began to view lafayette as a royalist, which would forever damage the public’s reputation of him. Though he continued to follow and urge the rule of law made by the constitution, he was drowned out by the mob and its prominent leaders. On June 30, 1791, Lafayette was then promoted to the rank of a Lieutenant General.

An event at the Champ de Mars was organized on July 17, 1791 by radical Cordeliers. At this event, signatures for a petition to abolish the monarchy or allow a referendum decide the fate of the royal family were gathered. About 10,000 people gathered at the Champ de Mars for the event. Two people accused of being spies were even hanged that day. Lafayette, though increasingly becoming less and less popular, rode into the Champ de Mars with his troops from the Guard to restore order. Once they arrived though, the troops were greeted with gunshots as the crowd threw stones at them. The soldiers began to fire at the crowd under order from their leader Lafayette when one of the dragoons went down, in the end killing and wounding dozens of people. This became known as the Champ de Mars Massacre. The event’s leaders, Georges Danton and Jean-Paul Marat, were forced to flee and go into hiding after martial law had been declared.

That September, the assembly finally finalized the constitution, leading to Lafayette’s resignation from the Guard in early October due to constitutional law being restored. His home in Paris was attacked soon after in attempts to injure his wife Adrienne. Because the people believed Lafayette was a royalist sympathizer after the massacre that July, his reputation suffered even more.The Lafayette’s returned to the Chavaniac estate in the province of Auvergne in October of 1791 shortly after his resignation.

Lafayette received command of the Army of the Centre based out of Metz on December 14, 1791 after his appointment to Lieutenant General earlier that year. France declared war on April 20, 1792 to Austria. Preparations to invade what is now Belgium—the Austrian Netherlands—began right away. Trying his best to bring the National Guardsmen and inductees into one force, Lafayette found that many of his troops were actually sympathizers with the Jacobins who loathed the officers holding superior ranks. It was a feeling felt by many in the army though, especially after the Battle of Marquain on April 29, 1792 where it was demonstrated when troops dragged their leader, Théobald Dillon, to Lilie. He was then torn up into pieces by the angry mob awaiting him. Rochambeau, one of the commanders of the army, quickly resigned. Working with Nicolas Luckner, Lafayette requested that the Assembly begin peace talks. Lafayette was greatly concerned what might happen if their troops faced another battle.

Radicals continued to gain influence, which Lafayette criticized in a letter to the Assembly in June of 1792 while he was at his field post. Lafayette stated in his letters that forcefully, the parties needed to be closed down. He realized that he misjudged the timing of the letter, as the radicals had taken full control of Paris. Lafayette made his way to the city later that month. On June 28, 1792, he gave a speech that denounced not only the radical Jacobins, but also other radicalist groups, before the Assembly, leading for him to be accused of actually deserting his troops. He tried to call volunteers to assist him in counteracting the Jacobins. But, hardly anybody showed up, and Lafayette left Paris. The mob burned him in effigy upon Robespierre’s statement that Lafayette was a traitor. On July 12, 1792, Lafayette was transferred and became the commander of the Army of the North.

Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick issued the Brunswick Manifesto on July 25, 1792, announcing that unless the king was unharmed, the Austrians and Prussians would destroy Paris. This ultimately led to the downfall of both the royal family and Lafayette. On August 10, Tuileries was attacked by a mob. Both King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette were taken to the Temple, a medieval fortress used as a prison at the time, after being imprisoned at the Assembly. From there, the Monarchy was officially abolished by the Assembly, with the royal family beheaded, King Louis the following January and Marie Antoinette in October of 1793. Danton soon issued a warrant for the arrest of Lafayette on August 14. Lafayette was planning to go to the United States and ended up in the Austrian Netherlands in the what-is-now Belgium area.

On behalf of a French group of officers, Jean-Xavier Bureau de Pusy, a subordinate under Lafayette, asked the Austrians for the right to transit through their territory. Originally, the Austrians granted this request. When they realized Lafayette was amongst the group of soldiers, they revoked their right to pass through. The King of Prussia, Frederick William II had once welcomed Lafayette. But because of the French Revolution, Lafayette was now viewed by him as one of the rebellion’s most dangerous formenter. Near Rochefort (now located in Belgium), Lafayette was taken prisoner by the Austrian forces.