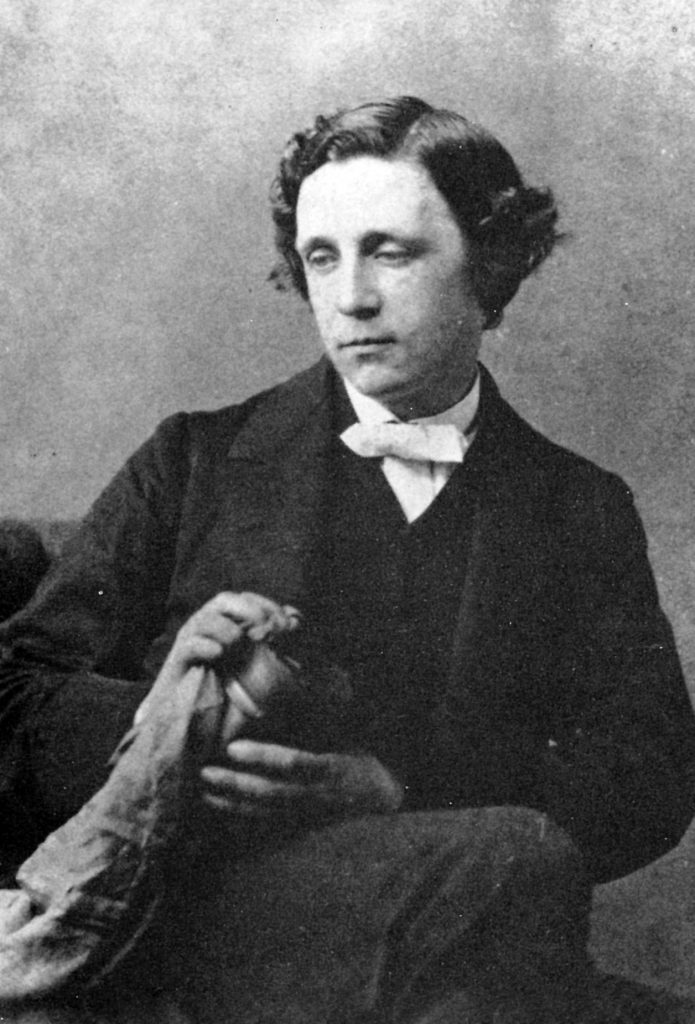

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, more commonly known by his pen name of Lewis Carroll. English writer, mathematician, Anglican deacon, logician, and photographer, Dodgson is best known for his novel Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland along with sequel Through the Looking-Glass. He also wrote many notable poems.

On January 27, 1832, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson was born in a small parsonage at Daresbury in Cheshire, which was near two other towns, Warrington and Runcorn. His father, Charles Dodgson, was a scholar and author, and his mother was Frances “Fanny” Jane Lutwidge, Charles Dodgson’s cousin. Charles Lutwidge was the first son, but third child, in his family, out of eleven children. He had three brothers and seven sisters. His father was given the living of Croft-on-Trees in North Yorkshire when Charles was eleven. The whole family then moved to the rectory in the town. For the next twenty-five years, this was where the family resided. At a young age, Charles developed a relationship at a young age with his father’s religious values and the whole Church of England.

Charles Dodgson was educated at home as a young boy. At the young age of seven, he was already reading books like The Pilgrim’s Progress. Along with most of his siblings, Charles suffered from a stammer, which also influenced his social life. Twelve year old Dodgson was sent to the Richmond Grammar School, which is now a part of the Richmond School, near Richmond, North Yorkshire.

When sent to Rugby School, a boarding school in Rugby, Warwickshire, in 1846, it was clear he was unhappy. However, he did do very well at the school when it came to academics.

After three years, at the end of 1849, Dodgson left Rugby. He then matriculated at Oxford University as a member of Christ Church, his father’s former college, in May of 1850. Dodgson did not go into residence until January of 1851, as he had been waiting for rooms to become available in the college. But only two days later, he was summoned home. His forty-seven year old mother, Frances Jane Lutwidge, had died of “inflammation of the brain,” so possibly from a stroke or meningitis.

While Dodgson was not always the hardest worker, he was exceptionally gifted. In Mathematics Moderations, he obtained a first-class honours in 1852. Not long after, he was nominated by an old friend of his father’s, Canon Edward Pusey, a Studentship. Then in 1854, he received first-class honours in the Final Honours School of Mathematics and graduated first on the list as Bachelor of Art. Though Dodgson remained at Christ Church to study and teach, he failed an important scholarship the following year. In 1855, his talent in mathematics and as a mathematician led him to win the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship. He held this for twenty-six years to follow.

On December 22, 1861, Dodgson became a deacon in the Church of England. He decided not to marry as well, because if he were to marry, he would have then been appointed to a parish. Dodgson saw himself unsuitable for parish work, so decided to remain unmarried.

Associating with children came naturally to Dodgson, especially because he had grown up with ten siblings, eight of which were younger. Some accounts have said that he was able to speak more easily around children and without his stammer, but there is no evidence to support this. He also entertained the dean of Christ Church Henry George Liddell’s children. Alice, Lorina, and Edith Liddell had all become Dodgson’s friends. He was also friends with author George Macdonald’s children and Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s. The Liddell children were especially close with him though. They would often visit him as a mathematics lecturer in his rooms at the college.

Alice would later on recall in 1932 that they “used to sit on the big sofa on each side of him, while he told us stories, illustrating them by pencil or ink drawings as he went along . . . . He seemed to have an endless store of these fantastical tales, which he made up as he told them, drawing busily on a large sheet of paper all the time. They were not always entirely new. Sometimes they were new versions of old stories; sometimes they started on the old basis, but grew into new tales owing to the frequent interruptions which opened up fresh and undreamed-of possibilities.”

Dodgson told the three girls, along with his friend Robinson Duckworth, the story of Alice’s Adventures Underground, which he had written for Alice. They had been rowing the children from Oxford up the Thames to Godstow and had a picnic before returning to Christ Church. Most of the story was based on a picnic they had all had a few weeks prior. Alice said to him before they parted, “Oh, Mr. Dodgson, I wish you would write out Alice’s adventures for me!”

Thus, he began writing the story. Dodgson added many more adventures along with the ones he had told Alice. After having written and illustrated the book, he gave it to Alice with no intentions of hearing the story again. While visiting the Liddells, novelist Henry Kingsley had picked up the book. Once he read it, he urged Mrs. Liddell to persuade the author, Dodgson, to have his book published. Surprised, Dodgson went to his friend George Macdonald for advice. Macdonald had already written many bestselling children’s books. He took the book home and read it to his children. Greville, his six year old son, declared after reading it that he “wished there were 60,000 volumes of it.”

So, Dodgson began revising it to have it published. While he took out the references to the picnic with the Liddell children, he added more stories that he had told them at different times, therefore making a volume of the length he desired. He was also introduced to John Tenniel, a cartoonist for a magazine. Dodgson commissioned him to do the illustrations for his new story.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was published in 1865 under Dodgson’s pen name, Lewis Carroll. The first edition was withdrawn due to bad printing. Only twenty-one editions still survive of it today. Later that year by Christmas, the reprint was ready to be published.

Slowly and steadily, the book became more and more successful. Dodgson even began to consider writing a sequel the following year. Again, based on more stories he told the Liddells, the sequel was written. Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There was published in December of 1871, though it was dated 1872. Some even thought it was better than the first.

The two volumes had been taken to form one by the time of Dodgson’s death at the end of the nineteenth century. it had already become the most popular children’s book in England, and by 1932, perhaps the most popular in the world. Queen Victoria herself even read and enjoyed the story. In fact, she enjoyed it so much, that she commanded Dodgson dedicate his next book to her.

Dodgson was not known just for his writing though. He was also a fine photographer of both adults and children. He did notable portraits of actress Ellen Terry, poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and poet and painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti, among others. At an early age, had the ambition of becoming an artist. Though this desire ended up failing, leading him to take to photography instead. Dodgson would photograph children in nearly every possible costume or situation, including nude studies. This hobby was abandoned in 1880, however. He felt this it took up too much time he could be better spending. It has been suggested that this decision was made so suddenly because of the impurity of his motive to do nude studies.

He had also published many humorous works of verse and prose prior to Alice’s Adventures. His earliest works were published anonymously, but under the pen name of Lewis Carroll, he published a poem in March of 1856 called “Solitude”. The name Lewis Carroll had been made when he took his name Charles Lutwidge and translated them into Latin. Therefore, he had come to Carolus Ludovicus, then reversed these two and translated them back to English, arriving at Lewis Carroll. As Charles L Dodgson, he published non academic works, including quite a few books on mathematics.

A fantastical “nonsense” poem called The Hunting of the Shark in 1876. It explored the adventures of a crew of nine bizarre tradesmen along with a beaver. The group had set off to find a shark. Afterwards, painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti became more and more convinced that the poem was about himself.

Dodgson attempted to make a comeback in 1895, which was thirty years after his Alice books had been published. He published two-volumes about Sylvie and Bruno, two fairy siblings. The books took place in rural England and the fairytale kingdoms that included Elfland and Outland, among others. Although it is considered a lesser work, it remained in print for over a hundred years. It was described as “one of the most interesting failures in English literature.”

In 1889, Dodgson invented the “Wonderland Postage-Stamp Case” as an attempt to promote letter writing. It was a folder made with close that had twelve slots, two of which were for inserting the common penny stamp. The folder was placed into a slip case that had a picture of Alice on the front with the Cheshire Cat on the back. He also invented a tablet used for taking notes in the dark called the nyctograph. It eliminated having to get out of bed when one woke up with an idea. It was made up of a gridded card that had sixteen squares. A system of symbols represented Dodgson’s alphabet he designed with letter shapes similar to the Graffiti writing system.

An early version of today’s Scrabble was also devised by Dodgson, along with a number of other games. He either invented or popularized the “doublet”, which was a brain-teaser that still remains popular. Altering one letter at a time, it changed a word into another, like slowly transforming Cat into Dog.

Until 1881, Dodgson continued teaching at Christ Church. He also remained there as a residence until he died. In 1889 and 1893, he published his last novels, Sylvie and Bruni and Sylvie and Bruno Concluded. He was met with limited success, only selling about 13,000 copies.

On January 14, 1898, Charles Lutwidge Dodgson was staying at his sisters’ home when he died of pneumonia after the influenza in Guildford. He was sixty-five, only two weeks short of sixty-six. His funeral was held at St. Mary’s Church and he was buried at the Mount Cemetery in Guildford.