Last week on History’s Nutcases, we covered Mad King George III of England. This week, we’re jumping back in time again to another Roman Emperor, one you’ve definitely heard of: Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus. For the sake of simplicity, we’ll just refer to him as Nero. He was the nephew to the famous Caligula, proving that, in this case, insanity really does run in families.

Nero was born on December 15, AD 37, in Antium, near Rome. According to Roman Historian Seutonius, his father was a murderer and a cheat, charged by Emperor Tiberius with supposed treason, incest, and adultery. He died when Nero was two. His mother wasn’t much better. After Nero’s father’s death, Agrippina remarried to a man named Crispus. She murdered him, and it’s likely she murdered her third husband, Emperor Claudius, as well.

Our nutcase wasn’t even supposed to be Emperor in the first place. He wasn’t in line at all. Emperor Caligula was supposed to have enough time to produce an heir, and besides, he exiled Nero’s mother, Agrippina and took Nero’s inheritance and sent him to be brought up by his aunt. His aunt was, coincidentally, the mother of the next Emperor’s, Emperor Claudius’ new wife, which sort of made Nero related to Claudius. When Caligula, his wife, and infant daughter were murdered, Claudius was made Emperor and he allowed Agrippina to return from exile. Conveniently, after going through three wives, Claudius married a fourth time in AD 49. He married Nero’s mother, Agrippina, and adopted Nero as his son. Since Nero was older than Claudius’ legitimate son, Nero became first in line for the throne.

In a questionable turn of events, Claudius died in AD 54. It’s unclear whether or not Agrippina murdered him in order to get her son on the throne, but I wouldn’t put it past her. Nero was established as emperor at the early age of seventeen.

During his early reign, he had three main influences: his tutor, Seneca, Burrus, and his mother, Agrippina. Agrippina was domineering and aggressive. It’s obvious she just really wanted to be Empress of Rome, because when Nero started taking the advice of Seneca and stopped listening to her, she started advocating for Nero’s little step-brother, Britannicus to be Emperor. In true Game of Thrones fashion, Britannicus died mysteriously just one day before he was supposed to be made a legal adult.

Things really started to go downhill after AD 59. For the first five years of Nero’s reign, Nero was described as a generous and reasonable leader. He lowered taxes, allowed slaves to have rights and take complaints to court. He supported arts and athletics, gave emergency aid to other cities, and completely got rid of capital punishment. But, in AD 59, Nero was fed up with his mother’s meddling. At his command, Agrippina was murdered. After her death, everything started to fall apart.

He still had Seneca and Burrus to keep him somewhat in line until the year AD 62. When Burrus died, and Seneca retired, there was no one to keep the young Emperor in check. Nero divorced his first wife, Octavia (who was actually his step-sister, ew), in favor of his mistress Poppaea. According to Seutonius, Nero tried, on several occasions to strangle Octavia, and failed. After that, he just accused her of adultery. He had Octavia executed. This marked the beginning of his killing spree. After that, Nero started to publicly and privately execute anyone who he thought was disloyal to him.

The stories go that he fancied himself a poet and musician. He played the lyre and gave public performances (which was very scandalous for any important person at the time). Other historians say that he also fancied himself a badass athlete, which wasn’t exactly the case. One time, he tried to enter the Greek Olympics, raced a ten horse chariot just to prove that he could, and almost died. He was awarded the laurel crown anyway, because, you know, he was the emperor. Other historical accounts say he liked to dress up as a female prostitute and wander the streets of Rome, trying to seduce men. He staged wild orgies, musical contests, and didn’t let anyone leave while he was performing his lyre. Seutonius writes of women giving birth during one of Nero’s recitals, and of men who pretended to be dead so they would be carried out. Later in his marriage to Poppaea, while she was pregnant with his second child, he kicked her to death in a fit of rage.

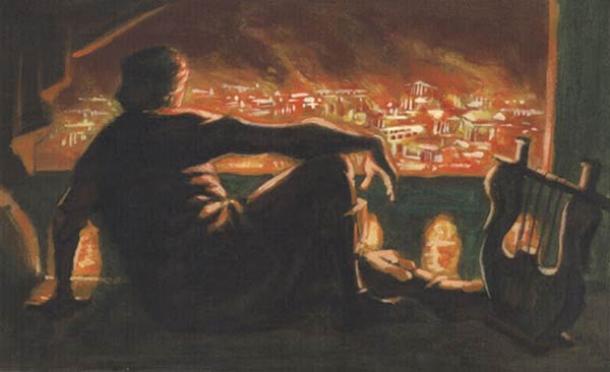

By AD 64, people were starting to notice that the Roman Emperor was a tad insane. They were conveniently distracted, though, when Rome caught fire. The city burned for ten days. 75 percent of it was burned to the ground. From his palace, Nero watched it, singing the Sack of Ilium and playing his lyre. People looked for a scapegoat, and rumors began to circulate that the fire had been Nero’s plan all along. In a desperate bid to redirect everyone’s attention, Nero blamed the Christians, who were still a new religion at the time. He used Rome’s anger toward this little sect of people to fuel his bloodthirsty need for violence. On his command, hundreds and hundreds of Christians were tortured, killed in the coliseums, or fed to wild animals. Seutonius writes that he even used Christians as torches for his garden parties. He would impale them on pikes, cover them in tar, and then set them ablaze and party beneath the light, remarking about the musicality of their screaming. If that’s not a bit over-the-top super-villian-esque, I don’t know what is.

A few years later, Nero had turned into a widely unpopular figure. Everyone in Rome thought he was over-indulgent, insane, and needlessly cruel. Gaius Julius Vindex rebelled against Nero because of Nero’s ridiculous tax increases to support his lavish, indulgent lifestyle. Gaius, together with his buddy, Galba, staged a revolt. Even though they were defeated and Galba was declared a public enemy, everyone started to support him anyway and lobby for him to be the new emperor. Nero had lost Rome. Even his own bodyguards defected in support of Galba.

Nero fled. He tried to head east, but even his own officers refused to obey him. When he went back to his palace, his guards and “friends” had fled. The Senate had condemned him to death by beating, and so he decided he would commit suicide. Ultimately, though, Nero couldn’t follow through. So, his secretary had to help. His last words were: “What an artist dies in me!”.

And so, thus ended the line of Judo-Claudian emperors, the line that had begun with Augustus Caesar, and ended in madness and blood.