We hear a lot about Ancient Egypt. The world has been pretty much obsessed with it since Howard Carter and his team first discovered King Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922. The Victorians loved hearing stories about it, and its practically undisputed that Egypt was a pretty cool place in the ancient world. The one thing we hardly ever hear about, though, is what in the world happened to it? Our history textbooks seem to skip from Egypt, to Greece, to Rome, with very little talk about what led to this great empire’s decline. Well, today we’re going to solve that mystery once and for all.

Background

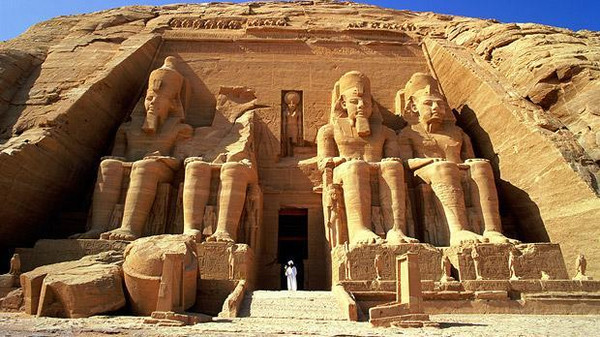

Ancient Egypt was one of the greatest empires of the pre-AD human world. The monuments that stand today are testimony of the heights that the Egyptians reached in science, mathematics, architecture, geometry, and cooperative efforts. Egypt was unified as one country around 3100 BC, and lasted as an independent nation for over 30 centuries. Few other ancient nations have rivaled its expansive culture, vast pantheon, or vibrant art. This ancient nation has enthralled us – even to the point of having its own field of study: Egyptology.

[ebaylistings]

By 332 BC, however, Egypt had undergone a massive decline. It had been broken apart and reunified half a dozen different times, had been conquered by the Persian Empire twice, and would see the rise of a new historical legend: Alexander the Great.

The Ptolemies

In 332 BC, Alexander the Great of Macedonia took down Egypt’s only other enemy: Persia. Egypt had, for ten years, been under Persian rule. Alexander swooped into Egypt after decimating Persia’s armies and swallowed up what was left of the Egyptian Empire. He built the famous city of Alexandria, named after himself, of course. Under Alexander’s rule, Egypt flourished, enjoying a sort of scientific and artistic Hellenistic renaissance based out of Alexandria.

After Alexander the Great died in 323 BC, just ten years after he’d conquered Egypt, his massive empire was split between his generals, who would head three great dynasties, each with control of a different part of the known human world. The Antigonids took Macedon. The Seleucids took what was left of the Persian Empire, mostly sprawling across Asia Minor, the Middle East, and Asia. It was the Ptolemies that would rule Egypt.

Under the Ptolemies, Egypt remained a fairly solid kingdom, still enjoying the fruits of Hellenization that Alexander the Great had brought in 332 BC. Under the rule of Ptolomy I, the Museum and Library of Alexandria was built. Scholars from all over the world came to study there. The Ptolemaic ‘Pharaohs’ relied on Greek mercenaries to keep Egypt safe, and Greek advisers to aid them in their decision-making. Greeks formed the upper crust of Egypt, replacing the native aristocracy, and imposed their religion and traditions on the rest of the kingdom.

Fourteen kings would reign in Egypt from roughly 306 BC to 30 BC, all of whom were named Ptolemy. The Ptolemaic kingdom, as it was called, saw the fall of the classical Greek Empire, the rise of the Roman Republic, and its shift to the imperial superpower that it would eventually become under Augustus Caesar.

Cleopatra and The Roman Empire

Cleopatra VII, more commonly known simply as ‘Cleopatra’, was born around 70 BC. She was the daughter of Ptolemy XII, the mother of the last Ptolemy of Egypt, and is considered by historians to be the last pharaoh of Egypt (it’s important to note that in the Egyptian language, the term, Pharaoh, is a gender-neutral title that could be taken on by a man or woman, depending on the needs of the time).

When her father died in 51 BC, the Egyptian throne passed to then 18-year-old Cleopatra and her 10-year-old brother, Ptolemy XIV. Her advisers, greedy for power, tried to assassinate her in 49 BC, forcing Cleopatra to flee to Syria.

When Julius Caesar arrived in Alexandria after the murder of his rival, Pompey, Cleopatra knew a rising power when she saw one, and wanted to turn Caesar into an ally. According to Roman scholars, she smuggled herself into the royal palace and seduced Julius Caesar. He then restored her and her younger brother to the throne, and was so smitten with her that he stayed in Egypt with her for several years.

Around 47 BC, Cleopatra gave birth to the last Ptolemy, Ptolemy Caesar. He was believed to be Julius Caesar’s child, and was often referred to as Caesarion, or ‘Little Caesar’.

In 45 BC, Julius Caesar took Cleopatra and their son back to Rome. All was not well in Rome, however, and in 44 BC, Julius Caesar was assassinated by his own senate, who feared his growing power. Cleopatra quietly returned to Egypt with Caesar’s son. By then, Cleopatra’s little brother had died. Wisely, Cleopatra decided to change her son’s name to Ptolomy XV and name him her co-regent. She broke her ties with Rome further by choosing to associate herself with the Egyptian goddess, Isis. Egyptian royalty was traditionally associated with divinity, and this bit of propaganda restored her popularity with the Egyptian populace, who began to call her the “New Isis”, or “Isis Reborn”.

Egypt was still standing on shaky feet, however. The Nile wasn’t flooding as well as it used to, causing a food shortage. So, Cleopatra once more turned her eyes to the equally unstable Rome, looking for new allies.

Decline

Rome was embroiled in a conflict between Julius’ Caesar’s three successors: Mark Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus; and his killers: Brutus and Cassius. Both sides were asking for Egyptian support, and Cleopatra swooped in on the opportunity. She sent troops to support Antony and Octavia, who then defeated Brutus and Cassius and divided the power between themselves. They were going to try and rule Rome together, but Cleopatra had other ideas.

In a bold political move, Cleopatra decided she would try and split these co-regents apart in order to take the power of Rome for herself. She set her sights on Mark Antony, Julius Caesar’s adopted heir and crowd favorite. Cleopatra believed that if she could win over Antony, she could win Rome itself. According to Plutarch, she seduced Mark Antony in 40 BC, lured him away from his wife, and the two of them spent a winter in Egypt together. After Antony returned home to Rome, Cleopatra gave birth to twins: Alexander Helios, and Cleopatra Selene.

Egypt continued to flourish under Cleopatra’s rule for ten more years. With Antony wrapped around her little finger, she convinced him to name her son, Cesarion, as future ruler of Rome, securing Cleopatra as queen of both Egypt and Rome itself. It was all going so smoothly, completely according to Cleopatra’s plan. In fact, it all would have worked out except for one tiny little detail: Octavian.

Octavian, furious with Antony’s decision, convinced the Roman Senate that Antony was weak, and got them to strip Mark Antony of his power as co-regent of Rome and declared war on both Antony and Cleopatra. His superior armies easily defeated Antony’s in 31 BC. Antony committed suicide, leaving Cleopatra and Egypt vulnerable to attack.

Months after Antony’s defeat, Octavian’s armies were on Cleopatra’s doorstep. Cleopatra shut herself in her bedchamber and quietly committed suicide. Her body was buried with Mark Antony. Octavian, by then renamed as Augustus Caesar I, first Emperor of Rome, murdered Cleopatra’s three children and brought Egypt to heel beneath the Roman Empire.

After that, Egypt would quickly decline under Rome’s harsh boot. The world would no longer perceive her as a shining star, but as merely another province. She would not appear in all her glory again until Howard Carter’s excavation of King Tutankhamen’s tomb in 1922.