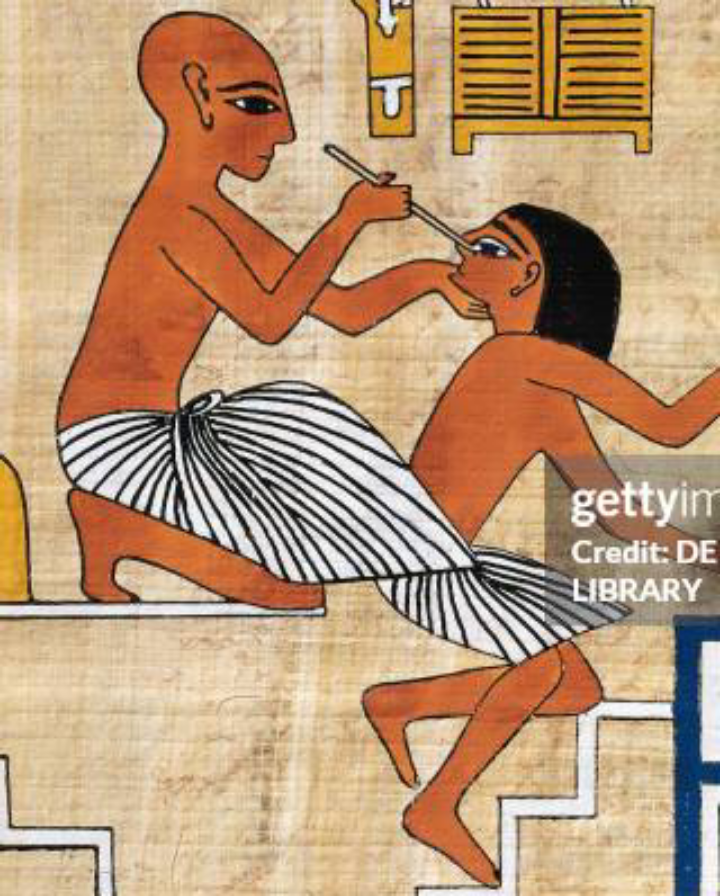

The boy’s eyes are wide open. A grown man leans in, one hand on the child’s head, the other at his face. No blood. No bandages. No obvious tools. To a modern viewer, it looks like a mix of a COVID test, a dental exam, and a kid trying to wriggle away.

Scenes like this appear in Egyptian reliefs and paintings from tombs and temples. A standing adult grips or steadies a child’s head and face. To Reddit, it looks like brain surgery or embalming gone wrong. To the ancient Egyptians, it meant something very specific.

What follows is a set of grounded what-ifs. Could this be medical treatment, punishment, or ritual instruction? Each scenario has to pass the same tests: does it fit Egyptian art rules, religion, and what we know from texts and archaeology? By the end, we will land on the most plausible reading and why it matters for how we read ancient images at all.

Was this ancient Egyptian brain or facial surgery?

When modern viewers see a hand near a face or nose, they jump to medicine. We live in an age of MRIs and nasal swabs. So our brains supply the closest match: medical procedure.

Ancient Egypt did have medicine that was surprisingly advanced for its time. The Edwin Smith Papyrus, copied around 1600 BCE from older sources, describes head injuries, skull fractures, and treatments with a cool, almost clinical tone. The Ebers Papyrus, from roughly the same period, lists hundreds of remedies, including for eye and nose problems.

Egyptian surgeons could set broken bones, stitch wounds, and drain abscesses. They knew that head injuries were dangerous and sometimes untreatable. They used bandages, splints, and herbal mixtures. There is even evidence of trepanation, small holes cut into skulls, although it seems rare and not always clearly therapeutic.

So the idea of “brain surgery” is not completely wild. But here is the catch. Egyptian art almost never shows medical procedures in action. Medical knowledge appears in papyri, not in carved reliefs on tomb and temple walls.

When Egyptians did depict specific jobs, they did it clearly. Scribes sit with palettes. Butchers cut meat with visible knives. Craftsmen hold chisels or drills. Surgeons, when shown at all in minor scenes, are usually seated, with a patient in front of them, and the action is obvious: bandaging, applying ointment, or cutting.

A man standing and gripping a child’s head with bare hands, no tools, no bandages, no jars of ointment, does not match that pattern. If this were a medical scene, we would expect clearer context: maybe a bed, a set of instruments, or a caption in hieroglyphs explaining the action.

There is another problem. Egyptian art is not a snapshot. It is a coded way of showing roles and ideas. The goal was not to capture a fleeting moment of treatment but to present an ideal, timeless version of life, ritual, or status. Surgery is messy, risky, and tied to misfortune. That made it a poor candidate for the eternal walls of a tomb chapel.

So what? If we rule out surgery, we learn our first big lesson: we cannot project modern medical imagery onto ancient art just because a pose looks vaguely clinical to us.

Is this punishment, discipline, or restraint?

The next modern instinct is darker. The man looks firm. The child looks like he might be pulling away. Is this a beating, a reprimand, or some kind of restraint?

Ancient Egypt did not shy away from depicting violence. Enemies are shown bound, beaten, and killed in temple reliefs. Pharaohs raise maces over kneeling captives. Prisoners are tied in long rows. These scenes are brutal, but they are also very clear. The message is power and domination.

Domestic discipline is harder to pin down. Texts and wisdom literature talk about teaching children, sometimes with a stick. One famous line from a New Kingdom instruction text says, in effect, that a boy’s ears are on his back and he listens when beaten. So corporal punishment existed.

Yet in tomb art, children are usually shown in affectionate or orderly contexts. They stand by their parents, often with a finger to the mouth and a sidelock of youth. They smell lotus flowers, play with pets, or accompany their fathers in processions. When a child is being guided, the adult might place a hand on the shoulder or hold a hand. The mood is calm, not violent.

A scene of a man gripping a child’s head could be interpreted as restraint, but then we ask: why carve that on a tomb wall or a high-status monument? Tombs were built to secure a good afterlife. People chose scenes that displayed piety, prosperity, and continuity of family. A moment of punishment or a child struggling would not fit that purpose.

There is also the issue of style. Egyptian artists used a limited set of poses. A hand at the chin or mouth often signals speech, feeding, or care, not aggression. A hand on the head can signal blessing, protection, or guidance. The same gesture can read very differently across cultures.

So what? By setting punishment aside as unlikely, we see how context and purpose shape what Egyptians chose to immortalize in stone. Tomb art is propaganda for a good life and afterlife, not a candid snapshot of bad parenting.

Could this be ritual instruction, grooming, or a coming-of-age act?

The third scenario fits better with what we know Egyptians liked to show: ordered ritual, family continuity, and the passing on of status or knowledge.

Children in Egyptian art are not just background. They are heirs, apprentices, and participants in ritual. A boy with a sidelock of youth and a naked or near-naked body is a stock figure. He might be the son of a noble, shown learning to hunt, fish, or serve in the temple.

Several types of scenes can look, to us, like a man gripping a child’s face.

One is grooming. Adults are shown anointing children with oils or perfumes. They might steady the head while applying kohl around the eyes. Kohl was more than makeup. It had protective and medicinal uses, shielding the eyes from sun and infection. Applying it required a steady hand close to the eye. In art, this can be reduced to a simple gesture: hand to face, no tiny applicator tool carved in.

Another is ritual instruction. Priests and scribes trained boys in recitation and gesture. A teacher might physically guide a student’s head or mouth to teach proper pronunciation or position in a ritual. Egyptian religion cared deeply about correct words and posture. A mispronounced spell could, in theory, fail. A hand near the mouth can signal speech or recitation.

There are also scenes of healing that are more spiritual than surgical. A priest might perform a protective rite over a child, touching the head while reciting spells. Amulets were pressed to the skin. The body was a surface for ritual action. The gesture could be both physical and symbolic.

Coming-of-age moments are harder to prove, but we know from texts and later depictions that boys were initiated into priesthoods and temple roles. Some rites involved shaving the head, changing clothing, or receiving specific insignia. A hand on the head could mark that transfer of status.

Egyptian art compresses time. A single scene can stand for a whole category of action: “the father caring for and instructing his heir” rather than one awkward moment of a kid flinching away from eye ointment. The child’s open eyes and alert posture fit that better than death or anesthesia.

So what? If we see the scene as grooming, ritual care, or instruction, the man is not a torturer or surgeon but a father, priest, or teacher. That shifts the image from horror to continuity: an adult shaping the next generation for life and for the gods.

Which scenario fits best, and what does it tell us about reading ancient art?

Without the exact relief in front of us, we cannot give a one-word answer. But we can weigh the options using what Egyptologists do every day: context, comparanda, and common sense.

First, context. Where such scenes appear matters. If the relief comes from a tomb chapel, surrounded by offerings, family, and ritual scenes, a medical emergency or punishment is out of place. If it is from a temple wall, part of a ritual sequence, then the gesture is almost certainly ritual.

Second, comparanda. Similar scenes from Old, Middle, and New Kingdom tombs show adults touching children’s heads and faces in non-violent contexts. Sometimes captions identify the figures as “his beloved son” or “his child, whom he loves.” No captions say “the boy being beaten” or “the child under surgery.” When tools are present in medical or craft scenes, they are drawn clearly. When they are absent, we should hesitate to invent them.

Third, common sense about what people choose to immortalize. Tomb owners paid artisans to carve what they wanted to live with for eternity. They chose banquets, hunting, offerings, and family. Even when they included scenes of work, those scenes supported the idea of order and provision. A panicked child under the knife does not fit that logic.

So the most plausible reading is that the man is performing some mix of care, grooming, and ritualized instruction. He might be steadying the child to apply kohl, to bless him, or to guide him in a formal act. The child’s open eyes and apparent tension are not a sign of torture. They are a side effect of how Egyptian artists drew bodies: stiff, profile, and stylized.

Ancient Egyptian art is highly stylized, not literal. A hand on a head can mean guidance or blessing, not assault. A child’s wide eye can be a symbol of youth and vitality, not terror.

So what? The way we answer this Reddit-style mystery matters because it exposes our own reflexes. We reach for surgery and COVID tests because that is our world. The Egyptians reached for ritual, continuity, and care. Learning to see their images on their own terms is the first step toward understanding a civilization that wrote its hopes and fears into stone.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Egyptian scene where a man holds a child’s head?

Scenes where an adult grips or steadies a child’s head in Egyptian art are usually read as care, grooming, or ritual instruction. They are unlikely to show surgery or punishment, especially when found in tombs, which favored idealized family and ritual images.

Did ancient Egyptians perform brain surgery on children?

There is limited evidence of trepanation and advanced treatment of head injuries in ancient Egypt, mainly from medical papyri and skeletal remains. However, such procedures were rare and are almost never depicted in tomb or temple art, so a carved scene of a man touching a child’s face is very unlikely to be brain surgery.

How did ancient Egyptian art show medical treatment?

When Egyptian art shows medical or craft activities, it usually includes clear tools, bandages, or work settings, and often appears in small register scenes. Most detailed medical knowledge is preserved in papyri, not in large tomb or temple reliefs, which focused on ritual, offerings, and family life.

Why do Egyptian children in art look like they are being grabbed or restrained?

Egyptian art used a rigid, stylized way of drawing bodies, with profile heads and simplified poses. A guiding or protective touch can look harsh to modern eyes. In context, these gestures usually signal guidance, blessing, or grooming rather than violence or restraint.