Picture Britain around the year 600. A Roman fort crumbles on a windy hill. Latin graffiti fades on a wall. A Saxon spearhead lies buried a few fields away. No one alive calls this place “Roman Britain” anymore, but the bones of that world are still everywhere.

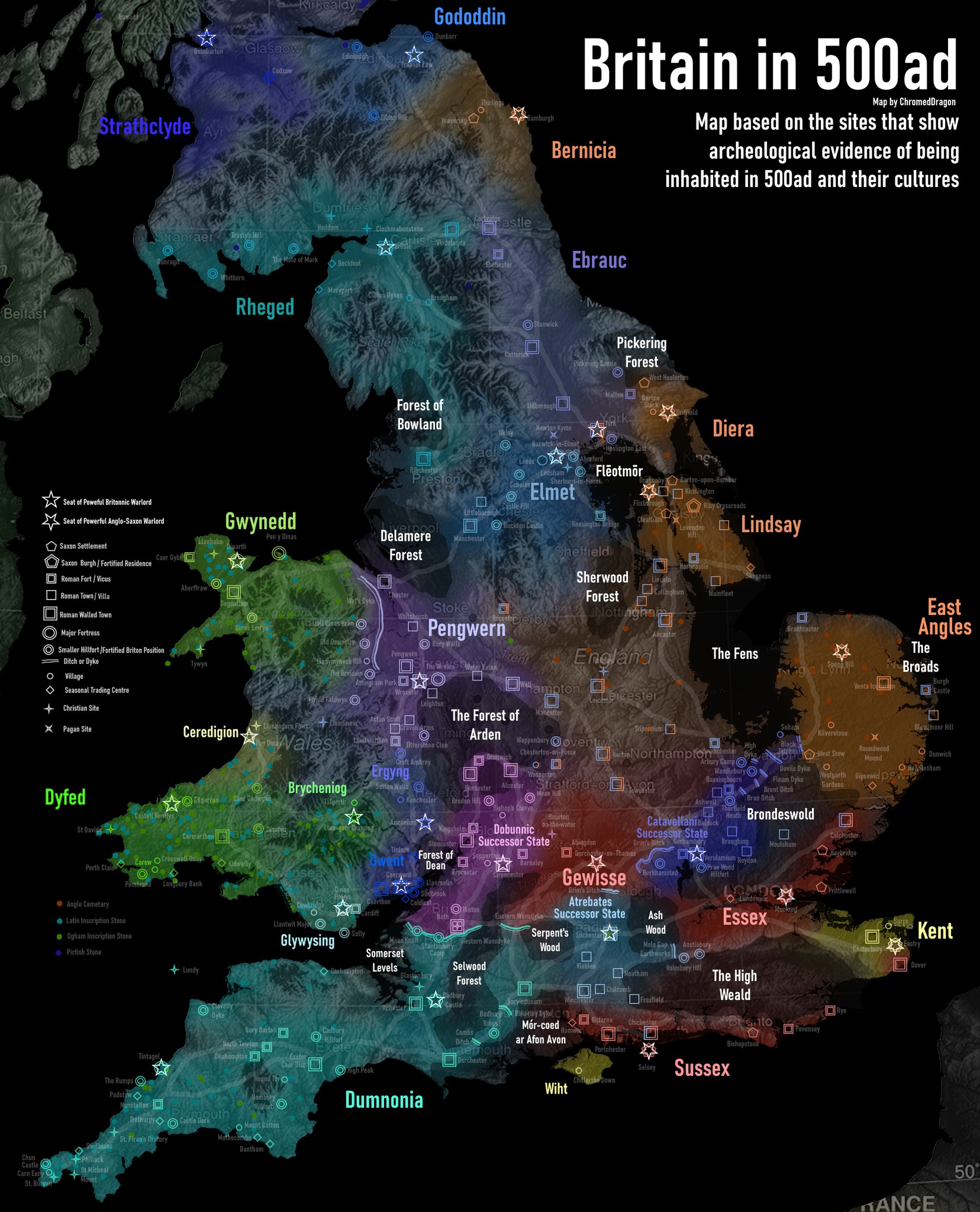

When people see a map of early medieval Britain based on archaeology, they are often shocked. It does not look like the tidy patchwork of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms from school posters. It looks messy. Overlapping. Full of gaps. And very, very local.

Archaeology-based maps of early medieval Britain show where people actually lived, traded, buried their dead, and built things. They are not about what kings claimed. They are about what shovels and trowels have found in the ground. By the end of this, you will know five big ways those maps rewrite the story of post-Roman Britain, and why it matters.

Early medieval Britain was not a clean break from Rome, nor a simple Anglo-Saxon takeover. Archaeology shows a long, uneven transition with survival, mixing, and regional pockets of power. Maps based on finds rather than later chronicles give a more accurate picture of who was where and when.

1. Roman Britain did not vanish overnight

What it is: Archaeology shows that Roman-style life lingered in parts of Britain for generations after the official end of Roman rule in 410. Villas, towns, and even some trade networks kept going, though in altered form.

On a map built from archaeology, you do not see a hard line at 410 where everything Roman disappears. You see late Roman coins turning up into the mid 5th century. You see pottery styles that continue, slightly simplified. You see people still burying their dead in late Roman cemeteries.

Take Wroxeter (Viroconium) in Shropshire. On paper, Rome pulls its troops out and the town should collapse. In the ground, it looks different. Excavations show timber buildings going up inside old stone shells, streets still in use, and signs of organized planning into the 5th and maybe early 6th century. It is not a thriving imperial city anymore, but it is not a ghost town either.

Or look at villas in the southwest, like Chedworth in Gloucestershire. Some show repairs and alterations in the 5th century. Mosaic floors get patched. Bath houses are reused. The lifestyle is shrinking and more local, but it is not simply wiped away by an invading wave.

Post-Roman Britain did not experience a sudden collapse everywhere at once. Archaeology shows a patchwork of survival, adaptation, and slow decline in Romanized areas.

Why it mattered: This slow fade changes the story of early medieval Britain from a dramatic “fall” to a staggered, regional transition. It means that when new powers, including Anglo-Saxon groups, appear on the map, they are not stepping into an empty island. They are interacting with existing communities that still remember Rome.

2. Anglo-Saxon settlement was dense in some areas, thin in others

What it is: The classic school map shows big colored blocks labeled “Angles,” “Saxons,” and “Jutes” spreading across lowland Britain. Archaeology-based maps tell a different story. They show dense clusters of early Anglo-Saxon material in some regions, and almost nothing in others.

Early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries and settlements are heavily concentrated in eastern and southern England. Kent, East Anglia, the Thames valley, and the East Midlands light up with furnished graves, sunken-featured buildings, and Germanic-style brooches. East Kent alone has dozens of 5th–6th century cemeteries like Buckland (Dover) and Finglesham, full of weapons, beads, and imported goods.

Move west and the picture fades. In much of Devon, Cornwall, and western Wales, early Anglo-Saxon finds are rare or absent. That does not mean no one lived there. It means that the people living there did not bury their dead in the same way, use the same objects, or leave the same kind of archaeological footprint as the newcomers in the east.

One sharp example is the line between Wessex and the British kingdoms to the west. In the 6th and early 7th centuries, the archaeology of eastern Wessex (Hampshire, Wiltshire) shows Anglo-Saxon style cemeteries and settlements. Cross into what is now Devon and Cornwall, and you get inscribed stones with Latin and Brythonic names, and very different burial customs. The map of finds shows a cultural frontier, not just a political one.

Anglo-Saxon settlement in Britain was not uniform. It was concentrated in fertile lowlands and river valleys in the east and southeast, and much thinner or absent in the far west and northwest.

Why it mattered: This uneven pattern undercuts the old idea of a simple “Anglo-Saxon conquest” that swept the whole island. It suggests a more complex mix of migration, settlement, and cultural change, with strong British survival in the west and north. The map of finds helps explain why later medieval Britain kept such sharp regional identities.

3. British kingdoms survived longer than many maps suggest

What it is: Archaeology reveals that Brittonic (often called “Celtic”) polities did not retreat to Wales and Cornwall overnight. They held large chunks of what is now England for centuries, especially in the north and west.

Look at the area historians call the “Old North,” roughly modern northern England and southern Scotland. Literary sources mention kingdoms like Rheged, Elmet, and Gododdin. For a long time, these sounded half-legendary. Archaeology has started to pin them down.

At Trusty’s Hill in Galloway, excavations found a high-status hillfort with 6th–7th century occupation, metalworking, and an inscribed stone using a Pictish-style symbol system. At Dumbarton Rock, the fortress of Alt Clut, layers of occupation show a powerful British kingdom controlling the Clyde well into the 8th century.

Further south, the kingdom of Elmet, around modern Leeds, leaves traces in place-names and burial evidence. Cemeteries and settlements in parts of Yorkshire show late Roman and British continuity into the 6th and early 7th centuries, before Northumbrian expansion. The archaeology matches the story that Elmet was only swallowed by Northumbria in the early 600s.

In the southwest, British power centers like Tintagel in Cornwall show imported Mediterranean pottery in the 5th–7th centuries, evidence of a local elite trading far beyond Britain. This is not a backwater. It is a plugged-in, post-Roman British kingdom with its own networks.

Early medieval British kingdoms survived as active, literate, and connected polities in large parts of Britain for several centuries after Rome, especially in the north and west.

Why it mattered: This survival changes the map from a simple “Celtic fringe” to a long contest between Brittonic and Anglo-Saxon powers. It means that early English kingdoms grew by absorbing existing British states, not just by filling empty land. That helps explain the deep cultural and linguistic layering in regions like Cumbria, Cornwall, and the Welsh border.

4. Trade networks stitched together a supposedly “dark” age

What it is: Archaeology-based maps of early medieval Britain often plot not just settlements and cemeteries, but also trade goods. When you map where imported pottery, glass, and metalwork turn up, a new Britain appears: one connected by sea routes and long-distance exchange.

One famous example is the distribution of Mediterranean and Gaulish pottery in 5th–7th century contexts. Sites like Tintagel in Cornwall, Dinas Powys near Cardiff, and Cadbury Congresbury in Somerset have shards of fine tableware and amphorae that once carried wine or oil from the eastern Mediterranean or Atlantic Gaul.

Plot those finds on a map and you see a western seaboard network. British and Irish elites are plugged into trade routes that run from the Mediterranean up the Atlantic coast to Brittany, western Britain, and Ireland. This is happening at the same time that eastern Britain is filling up with Anglo-Saxon cemeteries and continental-style goods.

On the east coast, different imports appear. In Kent, sites like Faversham and the cemetery at Buckland (Dover) show Frankish brooches, glass, and pottery from northern Gaul. The archaeology matches Bede’s story that Kent’s kings had close ties to the Frankish world, including royal marriages.

Even in so-called “dark age” Britain, imported goods and distribution patterns show that elites used long-distance trade to build status and power. Ports, river mouths, and coastal strongholds become key dots on the map.

Why it mattered: These trade maps break the myth of a sealed-off, isolated Britain after Rome. They show that different regions of Britain were plugged into different economic and cultural circuits. That helps explain why early medieval kingdoms developed such varied laws, art styles, and church connections.

5. The church drew its own map across kingdoms

What it is: When you map early medieval churches, monasteries, and Christian inscriptions, you get yet another Britain. Ecclesiastical sites often cut across political borders and ethnic lines, creating a religious geography that did not always match royal frontiers.

In western Britain and Ireland, early Christian inscribed stones appear from the 5th century onward. Many carry Latin texts and sometimes ogham, a script used for early Irish. Cornwall, Wales, and western Devon are dotted with these stones. They show a Christian, Latin-literate culture persisting and adapting after Rome, long before Anglo-Saxon England converts.

In the north, monasteries like Iona (founded c. 563) and Lindisfarne (founded 635) become powerhouses. Iona, off the coast of modern Scotland, was founded by the Irish monk Columba and influenced both Pictish and Northumbrian elites. Lindisfarne, on the Northumbrian coast, produced the Lindisfarne Gospels in the early 8th century, a masterpiece of Insular art that blends Irish, British, and Anglo-Saxon influences.

On a map, these monastic centers look like hubs with long spokes. Iona sends missionaries to the Picts and to Northumbria. Canterbury, founded as an archbishopric after Augustine’s mission in 597, connects Kent to Rome and the Frankish church. The result is a religious map that overlaps with, but does not simply mirror, the political one.

Church sites also mark where different traditions met. The Synod of Whitby in 664, held in Northumbria, is famous for choosing Roman over Irish practice on the date of Easter and other issues. Archaeologically, you see both Irish-style and Roman-style influences in Northumbrian monastic sites before and after this date, from burial customs to art motifs.

The spread of early medieval churches and monasteries created a network of literacy, law, and culture that crossed ethnic and political boundaries in Britain.

Why it mattered: The church’s map helps explain how ideas, texts, and artistic styles moved across Britain. It also shows why later political units, like the English kingdom, could be imagined at all. Long before there was a united England, there were church networks that linked Kent, Northumbria, Mercia, and British regions into shared conversations.

Put all these layers together and that archaeological map of early medieval Britain starts to make sense. There is the ghost of Rome, lingering in towns and villas. There are dense Anglo-Saxon settlement zones in the east, and British strongholds in the west and north. Trade routes tie western promontory forts to distant coasts. Monasteries and churches draw their own web across it all.

Why does this matter now? Because the way we picture the past shapes how we think about identity, borders, and change. The archaeology-based map of early medieval Britain refuses simple stories. It shows an island of overlapping peoples, stubborn survivals, and slow shifts. Not a clean break, but a long argument over what Britain would be.

Frequently Asked Questions

What did Britain look like in the early medieval period?

Archaeology shows early medieval Britain as a patchwork of surviving Romanized communities, new Anglo-Saxon settlements in the east and south, and enduring British kingdoms in the west and north. Trade routes and church networks cut across these regions, creating overlapping cultural zones rather than neat political blocks.

Did the Anglo-Saxons completely replace the Britons?

No. Anglo-Saxon material culture is dense in eastern and southern England, but western and northern regions show strong continuity of Brittonic communities and kingdoms for centuries. The evidence points to a mix of migration, cultural change, and political conquest, not a total replacement of the population.

How do archaeologists map early medieval Britain?

They plot finds like cemeteries, settlements, pottery, metalwork, coins, and church sites on maps, then date them by style, context, and scientific methods. This creates a picture of where different cultural traditions and economic networks were active in different centuries, independent of later written borders.

Was early medieval Britain really a “dark age”?

The term “dark age” is misleading. While written sources are patchy, archaeology reveals active trade with the Mediterranean and Gaul, complex local politics, and thriving church and monastic networks. The period was turbulent, but not culturally or economically blank.