Many experts say: cooking is what makes us human.

Last week, archaeologists may have found the earliest evidence of cooked food to-date. A group of international archaeologists working in the Saharan Desert in Lybia have uncovered several unglazed cooking pots. When analyzed, it was revealed that they’re over 10,000 years old. It’s an immense find, giving us vital insight into how the earliest humans began to cook.

Until now, archaeologists have known virtually nothing about how humans first began to process plants for food. Now, the 110 fragments of pottery found in Takarkori and Uan Afuda are yielding data from organic residue analysis that’s telling us what kind of foods were cooked in the vessels, including land-based leafy plants, wild grains, and even aquatic plants! There were traces of fig tree, and cinnamon, star anise, and nutmeg, too. The residue had been preserved in the fabric of the unglazed pottery. These plant signatures also tell us that humans had been processing plants in the Libyan Sahara for over 4,000 years.

A raw diet is extremely hard to digest and takes a very long time to do so. Early humans spent a good part of their day just breaking down their food. With the invention of cooking, humans were able to spend less of their time just digesting their food and more of their time in creative and inventive pursuits, and plants that were once indigestible became edible.

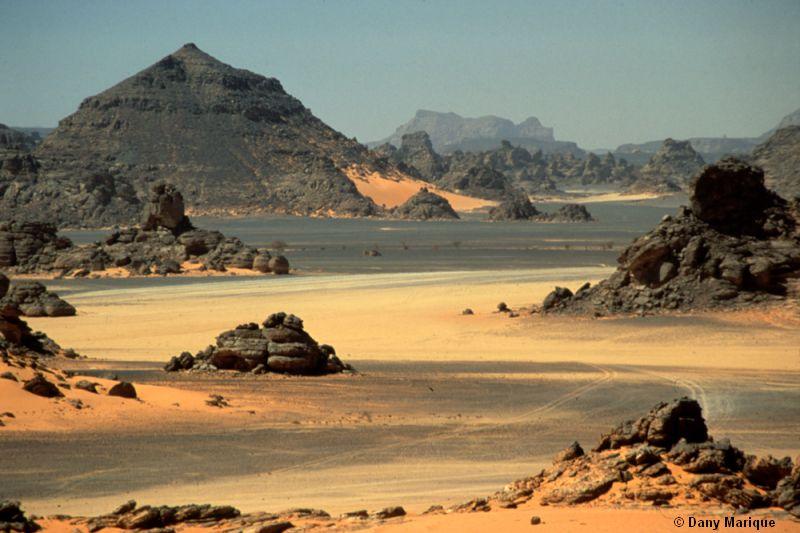

It’s also obvious that the Sahara Desert hadn’t always been as large as it is today. Ten-thousand years ago, early humans were able to harvest enough land-based plants and grasses and hunt enough animals to survive and even have time to sit down and decide to cook their food. But, perhaps the most important part of this study is that it shows that humans began to cook long before they began to farm. Hunter-gatherers understood the importance of cooking their food, and didn’t just decide to cook their food after they’d already begun domesticating it.

“These findings also emphasize the sophistication of these early hunter-gatherers in their utilization of a broad range of plant types, and the ability to boil them for long periods of time in newly invented ceramic vessels would have significantly increased the range of plants prehistoric people could eat.” – Dr. Julie Dunne, post-doctoral research associate with Bristol’s School of Chemistry.

The international team of archaeologists was lead by the University of Bristol. They worked with colleagues with Sapienza, University of Rome, and the Universities of Modena and Milan. The research paper was funded by the UK’s Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), and published December 19th, 2016, in Nature Plants.