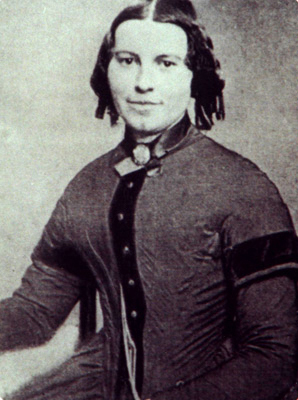

Clarissa “Clara” Harlowe Barton, an American Civil War nurse, is most notably known for being the founder of the American Red Cross and her humanitarian work. She is considered to be a pioneer of nursing and also worked as a teacher and patent clerk.

On Christmas day of 1821, Clarissa Harlowe Barton was born to Captain Stephen Barton, a local militia member, and Sarah Stone Barton in North Oxford, Massachusetts. Clara had two older brothers and two older sisters. At three years old, she began attending school with Stephen, her brother. Barton was known to be very shy and timid as a child, though she quickly became close friends with Nancy Fitts and was skilled when it came to reading and spelling. When her brother David had fallen off a barn roof and was left with a bad injury, so she nursed him back to health. Barton was only ten at the time, and was taught how to give him the proper medicine prescribed and how to place leeches on his body and bleed him. Even after doctor’s had given up trying to help him to recover, she continued to and he was eventually able to recover fully.

In attempt to get their daughter to be less shy and more outgoing, Barton was sent to Col. Stones High School. However, this only worsened Barton’s shyness and she refused to eat and fell into state of depression. So, her parents had her come back home so she could try and recover. One of her paternal cousins had died around the same time, leaving his wife with four children. So, Clara Barton and her family moved to help her out. The family’s new house was in need of repairs and repainting, so Barton tasked herself with completing those jobs. Not wanting to feel like a burden on her family, she was at a loss of what to do when she finished repairing the house. She played with her male cousins and became skilled at horseback riding and other activities around the farm. When she injured herself, her mother questioned if they should be allowing their daughter to play with the boys. One of her female cousins was then invited to the house by Sarah Barton to try and help Clara with her femininity and gain proper social skills.

Still very shy, Barton’s parents persuaded her to become a teacher to overcome it. In 1839, seventeen year old Barton received a teacher’s certificate. She took great interest in working as a teacher, even campaigning for children of workers to be able to receive a proper education. During her time as a teacher, Barton did many projects which led her to be able to overcome her shy personality and even demand that she be payed the same as men. She was skilled at her profession and was able to handle even the worst behaved children and gain their respect. For twelve years, Barton worked as a schoolteacher in Canada and West Georgia. To further her education, she pursued writing and language in New York at the Clinton Liberal Institute in 1850.

Barton was contracted in 1852 to open up a free school in the town of Bordentown, New Jersey. The school was very successful when it opened, and Barton had to hire another woman to teach with her when they had over 600 students. Because the school was so crowded, the town raised enough money to build a new one. She lost her job as principal with the completion of the new school building when the school board elected a man to the job. Instead she was given the job of “female assistant”, working in harsh environments. This caused Barton to have nervous breakdowns, so she quit her job at the school.

Three years after she opened the school, Barton moved from Bordentown to Washington D.C. There, she worked in the US Patent Office as a patent clerk. She was the first woman to work in the federal government with a salary that was equal to that of a man. However, she was demoted to a copyist when many politicians agreed women should not be given jobs in the federal government. After only a year, Barton had to leave her job when James Buchanan. For three years Barton lived with various family members and friends back in Massachusetts before returning as a temporary copyist when Abraham Lincoln became president in 1861. She had hopes that working as a copyist could help more women to get government jobs.

Shortly before her father passed away in early 1862, the two of them spoke about the war effort and he convinced her that, as a Christian, it was her duty to go and help the soldiers. A few months later, she traveled back to Washington that April to gather medical supplies. During the war, the Ladies’ Aid Societies would send bandages, food, and clothing. Quartermaster Daniel Rucker gave her permission to

work as a nurse on the front lines that August after Barton had begged him to. People who believed in her cause gave her support and became patrons, Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts being the most notable and supportive.

At first, Barton distributed stores, cleaned field hospitals, applied dressing, and served food to wounded soldiers after battles such as Cedar Mountain, Second Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and others. She and Colonel John J. Elwell began a romantic relationship in 1863, though Barton would never marry. Union General Benjamin Butler appointed her as “lady in charge” of the hospitals located at the from of the Army of the James in 1864. During her time as a nurse, a bullet once tore through her dress sleeve without harming her, but killed the man she had been tending to at that moment. Her hard work as a nurse earned her the nickname of the “Angel of the Battlefield”.

When the war ended in 1864, Barton discovered that many families of soldiers who were dead had been sending letters to the government asking about their relative. These soldiers were marked as “missing” though they had died in battle and were buried in unmarked graves. All the letters were going unanswered, so Barton asked and obtained permission from President Lincoln to officially respond to the letters. For some time, she ran the Office of the Missing Soldiers located in Washington D.C. With help from her assistants, Barton wrote 41,855 replies to the families of soldiers that had gone missing or were killed in battle. They were able to locate over 22,000 men that had gone missing. She spent her summer in 1865 finding, burying, and identifying soldiers who had died while being kept in Andersonville prison camp in Georgia. For four years, Barton would continue to do this. She buried over 20,000 Union soldiers that had died and marked their graves. $15,000 was given to her by Congress towards the project.

From 1865-1868, Barton traveled around the country to deliver lectures speaking about her experiences during the war and gaining widespread recognition. Her and Susan B. Anthony became friends during this time, and though Barton did not work as a suffragist, she began a long time association with the movement. Not only did she become associated with the woman’s suffrage movement, but she also became a civil rights activist after meeting Frederick Douglass. Touring around the country made her quite mentally and physically exhausted though, so, under doctor’s orders to go somewhere that would give her a break from her work, she traveled to Europe in 1868 after closing the Missing Soldiers Office. Barton was introduced to the Red Cross in 1869 while on a trip to Geneva, Switzerland. Dr. Appia introduced it to her, and later invited her to be a representative for the Red Cross branch in America. He also helped her to raise money when she began to establish the American Red Cross.

When the Franco-Prussian War first began in 1870, Barton helped the Grand Duchess of Baden to prepare military hospitals and aid the Red Cross society during the war. The two became longtime friends and helped establish sewing factories so women would be able to aid the war effort as well. Barton was the superintendent of supplying work to poor people in Strasbourg in 1871. She was also put in charge of publicly distributing supplies to Parisians. When the war ended in May of 1871, Barton received the Golden Cross of Baden and the Prussian Iron Cross, two honorable decorations.

She returned home to the United States after the war. Upon her arrival home, she created the movement for the International Committee of the Red Cross to get recognition by the U.S. government in 1873. Five years later, during a meeting with him President Rutherford B. Hayes, he pointed out to her that majority of Americans believed the country would never again face a war r something as terrible as the Civil War. She finally succeeded after President Chester A. Arthur was elected in 1881. This time, she argued that the American Red Cross would not only be there to help during wars, but also during other crises like natural disasters.

The first official American Red Cross meeting was held on May 21, 1881 at her apartment in Washington D.C. with Barton as the society’s president. On August 22, 1882, the first local American Red Cross society was founded in Dansville, Livingston County, New York where Barton also had a home. In 1884 they helped when the Ohio river flooded in Texas and have out food and supplies during the 1887 famine. The American Red Cross took workers to Illinois after an 1888 tornado and went down to Florida that same year when yellow fever broke out. Barton led fifty doctors and nurses down to Johnstown, Pennsylvania after the Johnstown Flood. She even sailed to Constantinople after a humanitarian crisis in the Ottoman Empire following the Hamidian Massacres. Barton Barton was able to open the first American International Red Cross in Turkey after spending a long time in Constantinople negotiating with Abdul Hamid II. In the spring of 1896 she traveled to the Armenian provinces to provide relief and humanitarian aid. Even at seventy-seven, Barton worked in Cuban hospitals in 1898. The American Red Cross also helped to aid refugees and civil war prisoners during the Spanish-American War from April in 1898 until that August. Her last field operation as President of the American Red Cross was in 1900 to help victims of the Galveston Hurricane and also establish an orphanage.

In 1904, Barton resigned from her place as President of the Red Cross due to criticism. At the time, she was eighty-three. Male scientific experts had forced her out of office because Barton reflected idealistic humanitarian while they reflected the efficiency of the Progressive Era. Sh went on to establish the National First Aid Society after her resignation.

Barton lived at her home in Glen Echo, Maryland from 1897 until her death. The building was also the headquarters or the Red Cross. In 1907, she published The Story of My Childhood, an autobiography. Then, Clarissa Harlowe Barton died on April 12, 1912 in her home from tuberculosis at ninety years old.