In March 1968, two boys slipped into an abandoned tenement on East 10th Street in New York City. Inside, they found a body on a cot, surrounded by empty beer bottles and religious pamphlets. No ID. No wallet. Just a young man, dead and alone.

Police logged him as a John Doe. He was buried in an unmarked grave on Hart Island, New York’s potter’s field. No one realized that the man on the slab was Bobby Driscoll, Disney’s golden child of the late 1940s and early 1950s, the voice of Peter Pan, and the first actor ever signed to an exclusive contract by Walt Disney himself.

Bobby Driscoll’s story is often reduced to a grim punchline: child star, drugs, dead at 31. The reality is more specific and more damning. It says a lot about Hollywood, about how America treated child actors, and about what happens when fame runs out.

Here are five hard truths that explain how a boy who flew over Neverland ended up in an unmarked grave.

1. Disney’s First Contract Child Star Was Treated Like a Disposable Prop

The first thing to know: Bobby Driscoll was not just any child actor. He was Disney’s experiment. In 1946, Walt Disney Productions signed him to an exclusive contract, something the studio had never done with a live-action performer before.

Disney wanted a reliable, wholesome boy they could plug into their new live-action features. Driscoll delivered. He co-starred in “Song of the South” (1946), headlined “So Dear to My Heart” (1948), and won a special juvenile Academy Award in 1950 for “The Window” and “So Dear to My Heart.” Then came his most famous role: the voice and live-action reference model for Peter Pan in Disney’s 1953 animated feature.

On screen, he was the ideal American boy. Off screen, he was an employee on a short leash. His contract meant he could not work for other studios without Disney’s permission. Disney controlled his image, his schedule, and, indirectly, his schooling and social life. When he was cute and bankable, this worked for everyone. When puberty hit, it did not.

The concrete turning point came in the early 1950s. As Driscoll’s voice changed and acne appeared, studio executives reportedly decided he no longer fit the clean-cut boy image. According to later interviews he gave, he found out he was dropped when his studio pass stopped working. No ceremony. No transition plan. Just a locked gate.

Disney’s first contract child star was treated as a tool: valuable when he fit the brand, expendable when he did not. That pattern mattered because it set the tone for how studios could use and discard young performers, with almost no thought for what came next.

2. Hollywood Had No Real Safety Net for Child Actors Growing Up

The second hard truth is structural. Mid‑century Hollywood had rules about child labor hours and trust accounts, but almost nothing about what happened when child actors aged out of their roles.

By the time Driscoll hit his mid-teens, the industry had already typecast him. He was the earnest boy, the wide-eyed innocent. Casting directors did not see a future leading man. They saw yesterday’s kid. When he tried to transition into more mature roles, the work dried up. He picked up a few scattered TV parts, minor film roles, and then the calls slowed to a trickle.

There was no studio counselor, no mandated career planning, no mental health support. Child actors were expected to either magically reinvent themselves or quietly disappear. Shirley Temple had already retired from acting by 22 and moved into public service. Many others simply faded into obscurity.

Driscoll did not fade quietly. He struggled to fit into regular schools after years on sets and tutors. He reportedly faced bullying from classmates who recognized him and resented his fame. That mix of lost status, stalled career, and social isolation is a familiar pattern in child-star stories, from Jackie Coogan in the 1920s to later cases like Dana Plato and Gary Coleman.

Hollywood’s lack of a safety net mattered because it turned a predictable life transition into a cliff. For Bobby Driscoll, that cliff led directly toward drugs, arrests, and exile from the industry that had raised him.

3. Early Drug Use and a Criminal Record Closed Doors Fast

The third hard truth is ugly and personal: Bobby Driscoll fell into drugs young, and the system around him was not built to pull him out.

By his late teens, he was reportedly using heroin. Public records show that in the late 1950s he was arrested multiple times, including for drug possession, forging checks, and assault. In 1961, he was sentenced to a term in Chino, the California Institution for Men, on a narcotics charge. He was in his early twenties.

When he got out, he tried to restart his acting career. Hollywood was not interested. A former child star with a drug record and a visibly worn face was a hard sell in an industry obsessed with fresh faces and clean reputations.

There are parallels here with later figures like Robert Downey Jr., who also battled addiction and arrests. The difference is that Downey came of age in an era when rehab narratives could be spun into comeback stories. In the 1950s and 60s, a narcotics conviction often meant permanent exile.

Driscoll’s drug use mattered not just because it wrecked his health, but because it branded him as unemployable. Once he was tagged as a problem, the same industry that had once built his entire identity now wanted nothing to do with him. That social and professional isolation pushed him further to the margins.

4. From Peter Pan to Warhol’s Factory: A Desperate Reinvention

The fourth truth is one that surprises many people: Bobby Driscoll did not simply vanish after Disney. For a brief, strange period in the mid‑1960s, he tried to reinvent himself in the New York art scene.

After leaving California, Driscoll drifted to Greenwich Village. There he connected with the circle around Andy Warhol’s Factory, a loose group of artists, hangers‑on, and would‑be stars. He wrote poetry, painted, and appeared in at least one off‑off‑Broadway production. Some accounts suggest he acted in or around experimental films, though the record is patchy.

This was not a clean new chapter. Friends from that period later recalled that he was still struggling with addiction and money. But it shows that he was not simply a passive victim. He tried to find a new identity that was not defined by Disney or Peter Pan.

The Warhol connection matters because it exposes a blind spot in how we talk about Driscoll. He is often frozen as a tragic child star, but in his thirties he was a man trying to make art and community in a very different subculture. That attempt failed, but it complicates the simple narrative of “Disney kid, then nothing.”

His time in the Factory orbit also shows how far he had fallen socially. In 1953, he was the voice of a major studio release. A decade later, he was scraping by in a fringe art world that could not pay his bills or keep him alive.

5. Anonymity in Death Exposed How Disposable Fame Can Be

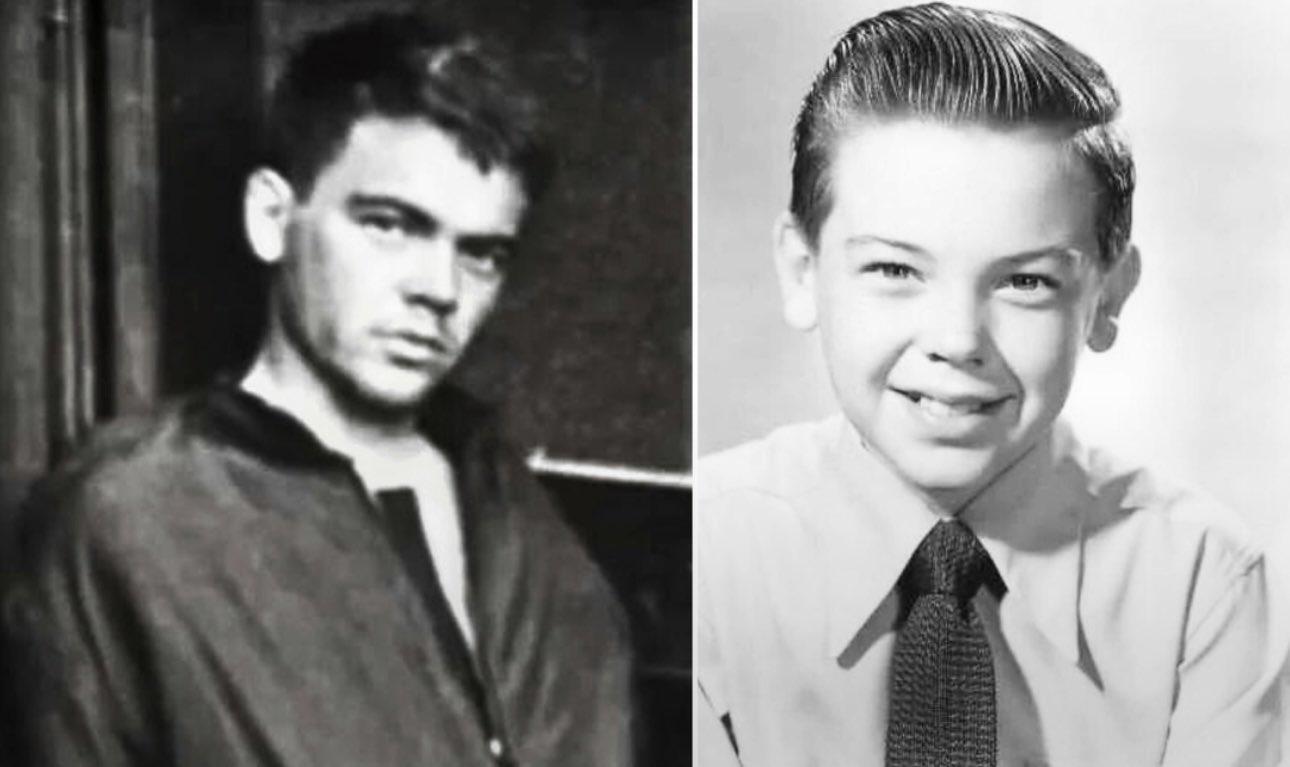

The final hard truth is the one that haunts people when they see those last photos: Bobby Driscoll died in near-total anonymity, and no one realized who he was for years.

The official record goes like this. On March 30, 1968 (the exact date is sometimes given as March 30 or 31), two children found his body in an abandoned building on East 10th Street in Manhattan. The police found no identification. An autopsy attributed his death to advanced arteriosclerosis, likely worsened by long-term drug use. He was about 31 years old.

With no one to claim the body, New York buried him on Hart Island, where the city sends its unclaimed dead. His grave was unmarked, one of many in a mass burial trench. The name “Bobby Driscoll” did not appear on any headstone.

His parents did not find out for about a year and a half. According to later reports, they had been trying to locate him and contacted authorities. Fingerprints taken at his autopsy were eventually matched to his old studio records. By then, his body was long gone into the anonymous rows of Hart Island.

That anonymity mattered in two ways. First, it made his story feel like a parable about Hollywood’s indifference. The boy who had once been the literal face and voice of Peter Pan died so far from the spotlight that even his death certificate did not carry his name at first.

Second, it turned his life into a cautionary legend. When people today share “one of the last photos of Bobby Driscoll” online, what shocks them is not just that he died young. It is that a person that famous could vanish so completely that the city buried him like any other unclaimed body.

His unmarked grave on Hart Island is the final, brutal symbol of how disposable fame can be. The boy who never wanted to grow up grew up, was discarded, and then, in a very literal sense, erased.

Why Bobby Driscoll’s Story Still Hits a Nerve

So why does a black‑and‑white photo of a gaunt man in his early thirties, labeled as “one of the last photos of Bobby Driscoll,” keep circulating online and drawing thousands of comments?

Because his story answers a question people keep asking about child stars: what happens when the cameras stop?

Driscoll’s life shows that early studio contracts gave kids money and fame, but almost no long-term protection. It shows how quickly a young actor could go from Disney’s favorite to a locked-out ex-employee. It shows how addiction, untreated and stigmatized, could erase whatever sympathy the industry might have had.

It also complicates the myth of Peter Pan. The boy who voiced the character who never grows up did grow up, and the world had no idea what to do with him. That irony is not just poetic. It points to a cultural habit of loving children on screen while ignoring the adults they become.

Today, there are more rules, more therapists on sets, more public awareness of what fame does to kids. But the basic tension is still there. We still consume child performances without really knowing what happens to those kids ten or twenty years later.

Bobby Driscoll’s unmarked grave is not just a sad footnote in Disney history. It is a warning label on the whole idea of childhood fame. The boy who once flew over London ended his life in a forgotten building in New York, and for a long time, no one even knew his name.

Frequently Asked Questions

How did Bobby Driscoll die?

Bobby Driscoll died in late March 1968 in an abandoned building on East 10th Street in New York City. An autopsy attributed his death to advanced arteriosclerosis, likely worsened by long-term drug use. He was about 31 years old and had no identification on him, so he was initially recorded as a John Doe.

Why was Bobby Driscoll buried in an unmarked grave?

Because police could not identify him and no family came forward at the time, Bobby Driscoll was treated as an unclaimed body. New York City buried him on Hart Island, its potter’s field for the unclaimed dead, in an unmarked grave. His identity was only confirmed about a year and a half later, when his fingerprints were matched to old studio records after his parents asked authorities to search for him.

Why did Disney drop Bobby Driscoll?

Disney dropped Bobby Driscoll in the early 1950s as he entered his mid-teens. His changing appearance, including acne, and his maturing voice made him less suitable for the boyish roles he had been known for. According to his later accounts, he discovered he had been let go when his studio pass stopped working. Once Disney no longer saw him as fitting their clean-cut child image, they stopped using him and did not help him transition to adult roles.

Did Bobby Driscoll ever work with Andy Warhol?

Bobby Driscoll spent time in New York’s Greenwich Village in the mid‑1960s and moved in circles connected to Andy Warhol’s Factory. He wrote poetry, painted, and appeared in experimental theater. Some sources say he was involved around the Factory scene, though the exact extent of his work with Warhol-related projects is unclear. What is clear is that he tried to reinvent himself as an artist after his Hollywood career collapsed.