PHOTO: travelingwithpurpose.com

Last week on Battles That Made History, we talked about the Battle of Waterloo, Napoleon’s famous final defeat that put an end to his warmongering and ushered in a brief time of peace for Europe.

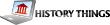

This week, we’re covering the battle of Gettysburg, the most important battle of the American Civil War, and the bloodiest battle in terms of American losses in US history. General Robert E. Lee’s losses would eventually spell ultimate defeat for the Confederate army, and irrevocably turned the tide of the American Civil War in the Union’s favor.

Crossing the Potomac

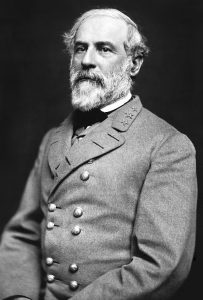

General George G. Meade. [PHOTO: wikimedia]

General Robert E. Lee. [PHOTO: wikimedia]

The current Union commander, Joseph Hooker, was slow to respond. Abraham Lincoln had lost faith in him, and so, just three days before the Battle of Gettysburg, he named General George Gordon Meade to succeed him as commander of the Union army. Meade ordered the immediate pursuit of Lee’s Army, some 75,000 men, which had already crossed the Potomac into Maryland and was making its way to Pennsylvania.

July 1

PHOTO: wikimedia

On July 1st, Lee assembled his army at Gettysburg, having approached from the south, intending to crush the Union army once and for all. Some of his men went into the town to get supplies, but found that Union soldiers had beat them to it. Since the bulk of the Union forces were still yet to arrive, the Confederates were able to push the Union soldiers back to Cemetery Hill, just a half mile south of the city.

Anxious to keep his advantage, Lee gave orders to General Ewell to attack Cemetery Hill. Ewell was the newest of Lee’s commanders, having replaced Stonewall Jackson after the latter was mortally wounded at Chancellorsville. When the order to attack came from Lee, Ewell refused to obey, believing the Federal position to be too strong to attack. In the time lost by his hesitance, the Union Army, led by General Winfield Scott Hancock, was able to show up in force and take defensive positions along Cemetery Ridge all the way to a nearby hill called Little Round Top. When three more Union corps arrived overnight, it was clear Lee’s initial advantage was lost.

July 2

![Overview of the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg [PHOTO: wikimedia]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/800px-Gettysburg_Battle_Map_Day2-706x1024.png)

Overview of the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg [PHOTO: wikimedia]

Finally, at 4pm, Longstreet opened fire on the Union line extending all the way from Devil’s Den to Little Round Top. In coordination, Ewell ordered a charge on Culp’s Hill and East Cemetery Hill. It was a bitter, bloody attack that raged for hours. The Federal troops managed to hold Little Round Top, but lost the nearby peach orchard, wheat field, and Devil’s Den. One of their commanders, Daniel Sickles was seriously wounded. In just one day, the combined losses on both sides totaled to 35,000 deaths.

July 3

The fighting died down for the night, but early in the morning of the next day, the Union forces surged back to try and retake their lost ground. A seven-hour firefight ensued. At the end, the Union forces were able to push the Confederates off of Culp’s Hill, regaining a strong defensive position.

Lee, frustrated with his commanders and at how close he had been to victory the day before, was not about to lose and was eager to gain more ground. He ordered a artillery barrage against Cemetery Ridge, at the Union center, and then sent commander George Picket and 15,000 troops to attack the Northern soldiers. It was a bad move. Picket and his men would have to advance over three-quarters of a mile through open terrain against well-defended Union lines. Even Longstreet protested.Despite everyone’s advice against it, Lee was persistent, and Picket obeyed him. The ensuing attack became known as Pickett’s charge. At 3PM, Lee ordered 150 Confederate guns to bombard the Union center. Then, Picket led his men forward. From behind stone walls, the Union infantry opened fire. It was a disaster. The Northern Vermont, New York, and Ohio regiments swooped down on the Confederate flanks. Lee and Longstreet could only watch helplessly as Pickett was surrounded and over two-thirds of his men were shot down.

After that, Lee martialed his forces, turned and retreated. There was nothing else he could do. He and Longstreet retreated to shore up their defenses and wait for an ensuing attack from the defending Union army.

The Turning Tide

![Photograph of the dead Union soldiers on the battlefield of Gettysburg. [PHOTO: wikimedia]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Battle_of_Gettysburg.jpg)

Photograph of the dead Union soldiers on the battlefield of Gettysburg. [PHOTO: wikimedia]

The Battle of Gettysburg was a crushing defeat for the Confederacy. Over 28,000 Confederate soldiers had lost their lives, numbering over one third of Lee’s army. Such a loss essentially spelled ultimate defeat for the Confederate States.

When he returned to Virginia, Lee tried to resign, but Southern president Jefferson Davis wouldn’t let him. Reluctantly, Robert E. Lee would go on to win a few other victories, but he knew the war was lost. Gettysburg had turned the tide in the Union’s favor for the rest of the Civil War.

![Cemetery Ridge as it looks today. [PHOTO: wikimedia]](https://historythings.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/High_Water_Mark_-_Cemetery_Ridge_Gettysburg_Battlefield.jpg)