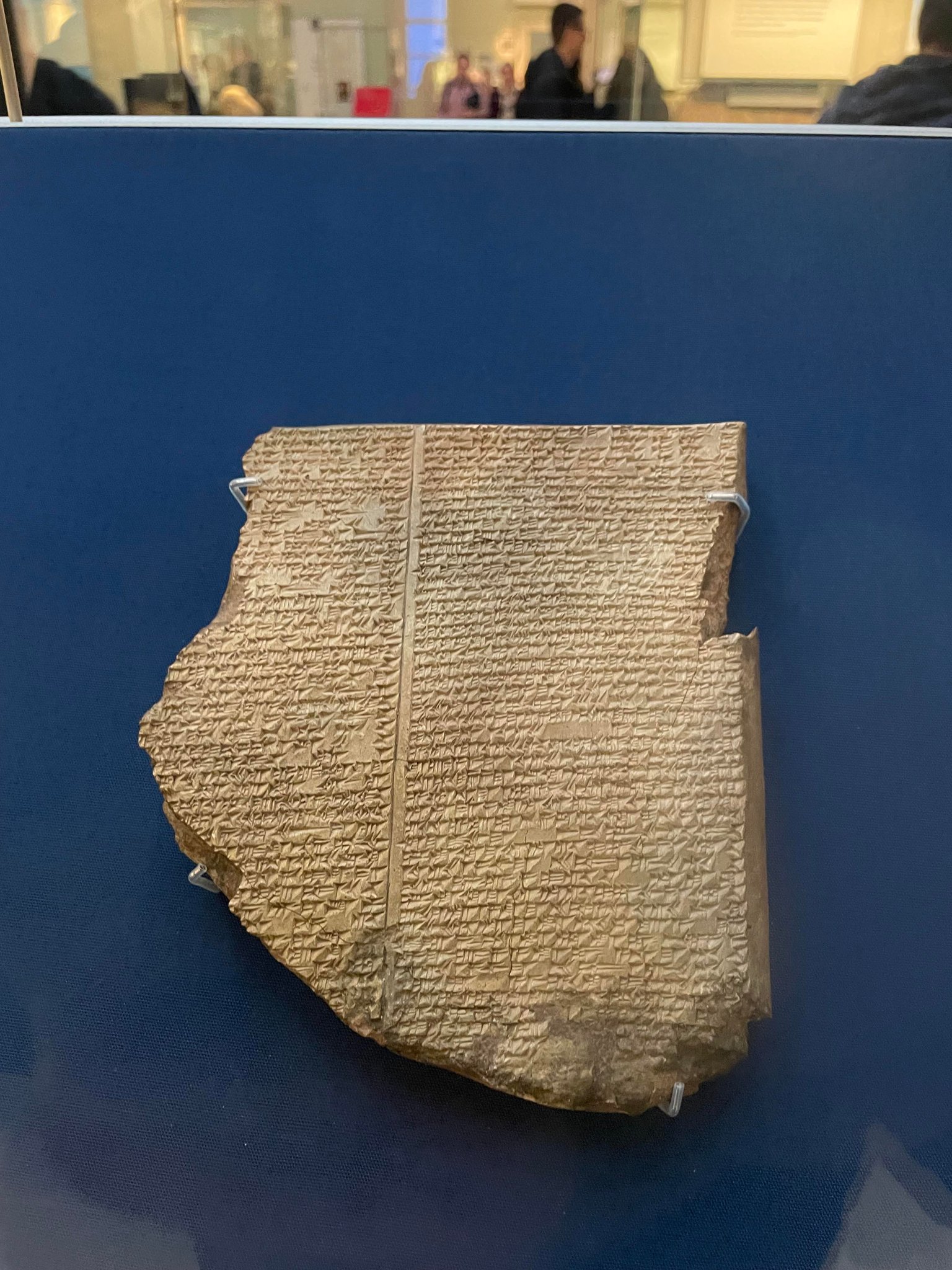

In a quiet glass case in the British Museum, a palm-sized clay tablet sits under soft light. To most visitors it looks like a broken brick covered in tiny chicken-scratch. But when scholars first translated it in the 19th century, they realized something unsettling.

The cuneiform lines described a man warned by a god about a coming flood. He built a boat. Loaded animals. Survived a world-destroying deluge. Sent out birds to test if the waters had receded.

It sounded a lot like the story of Noah. Except this tablet came from ancient Assyria, from the library of King Ashurbanipal, and it was written more than a thousand years before the Book of Genesis took its final form.

By the time you walk away from that case, you are not just looking at a relic. You are staring at a piece of evidence that ancient Mesopotamians were telling flood stories long before the Hebrew Bible, and that myths traveled, merged, and evolved across cultures.

What was Ashurbanipal’s Flood Tablet, exactly?

When people online say they “saw Ashurbanipal’s Flood tablet,” they are usually talking about one of the clay tablets from the library of Ashurbanipal that preserves a Mesopotamian flood story. The most famous of these is Tablet XI of the Epic of Gilgamesh, discovered at Nineveh and now in the British Museum.

The Flood Tablet is a baked clay tablet covered in cuneiform script, written in Akkadian, the main literary language of Mesopotamia in the first millennium BCE. It dates to the 7th century BCE, during the reign of Ashurbanipal of Assyria, though the story it records is older.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, the flood story appears when the hero Gilgamesh meets Utnapishtim, a man who survived a divine flood and was granted immortality. Utnapishtim tells how the god Ea warned him that the gods planned to wipe out humanity. He was told to build a huge boat, bring his family, craftsmen, and “the seed of all living things,” then ride out a storm that lasted days. Afterward he released birds to see if the waters had gone down.

So the “Flood Tablet” is not a random myth. It is a specific clay tablet from Ashurbanipal’s royal library that preserves the Mesopotamian version of a world-destroying flood, centuries before similar themes appear in the Hebrew Bible.

That matters because it gives us a concrete, datable artifact that proves flood myths were written down in Mesopotamia long before the biblical account, which changes how historians think about the origins and circulation of ancient stories.

What set it off: why did Mesopotamians tell flood stories?

People often assume the flood story must be “copied” from one text to another. The reality is messier and more human. Mesopotamia, the region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (modern Iraq and parts of Syria and Turkey), was a place where water gave life and death in equal measure.

Rivers flooded unpredictably. Canals broke. Whole fields could vanish under muddy water. Archaeologists have found evidence of major flood layers in several Mesopotamian cities, though not one single flood that wiped out the whole region. To people living on low-lying floodplains, a “world-destroying” flood did not feel theoretical.

The earliest known Mesopotamian flood story appears in the Sumerian tale of Ziusudra, probably composed in the early second millennium BCE or earlier. Later, the Old Babylonian Atrahasis Epic told of a god sending a flood to wipe out noisy, overpopulated humans, with one man warned to build a boat. The Gilgamesh version, like the one on Ashurbanipal’s tablet, is a later retelling of that tradition.

So why floods? Because they were the most terrifying and memorable way the environment could reset human life. A flood myth is a story about cosmic control, divine anger, and survival in a world that can drown you overnight.

That context matters because it shows the flood story was not invented out of nowhere. It grew out of real environmental risk in Mesopotamia, which made the idea of a divine flood both believable and powerful as a tool for thinking about human behavior and the gods.

The turning point: when the tablet met the Bible

The clay tablet sat buried in the ruins of Nineveh for more than two thousand years. The turning point came in the mid-19th century, when British and French excavators began digging in what is now northern Iraq.

In 1849, the British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard started uncovering the palace and library of Ashurbanipal at Kouyunjik, part of ancient Nineveh. Thousands of broken clay tablets were shipped back to London. For years they sat in the British Museum, mostly unread, because very few people could read Akkadian cuneiform.

Enter George Smith, a self-taught Assyriologist and former banknote engraver. In 1872, while working through the tablets, he pieced together one that described a massive flood, a boat, animals, and birds sent out over the waters. When he realized how close it was to the story of Noah, he reportedly jumped up and ran around the room in excitement.

Smith’s translation of the Flood Tablet was published and caused a sensation. Victorian readers, raised on the Bible as literal history, were confronted with a much older text telling a very similar story. Newspapers splashed it as proof that the Bible had “pagan” sources. Clergy scrambled to explain it.

From that moment, Ashurbanipal’s Flood Tablet was no longer just a relic of Assyria. It became Exhibit A in a global argument about how ancient the Bible really was, how myths traveled, and whether sacred texts were unique or part of a shared Near Eastern tradition.

That turning point matters because it shifted biblical studies, archaeology, and public debate. The tablet forced scholars to treat the Bible as one ancient text among others, not as a sealed, isolated account.

Who drove it: Ashurbanipal, his scribes, and the modern decoders

The tablet exists because one Assyrian king was obsessed with books.

Ashurbanipal ruled the Neo-Assyrian Empire from about 669 to around 631 BCE. He is remembered both as a ruthless conqueror and as a rare king who could read and write cuneiform himself. He ordered his officials to collect “all the tablets in all the lands” and bring them to his capital, Nineveh.

His scribes copied older Sumerian and Babylonian works onto fresh clay tablets. That is why a flood story that probably originated centuries earlier in southern Mesopotamia appears in a 7th-century Assyrian library. The library was an ancient archive project, preserving literature, rituals, omens, and myths.

Without Ashurbanipal’s collecting mania and the scribes who copied the Epic of Gilgamesh, the flood story might have vanished with decaying clay in some provincial temple.

On the modern side, several figures mattered. Layard’s digs brought the tablets to light. Henry Rawlinson and others helped crack cuneiform. George Smith recognized the flood story and made it public. Later scholars like Samuel Noah Kramer and Andrew George refined the text and its dating.

So when you look at that tablet, you are seeing the joint work of an ancient king who wanted every story in his library, anonymous scribes who pressed wedges into wet clay, and 19th-century scholars who learned to read a dead script and had the nerve to say, “This sounds a lot like Noah.”

Those people matter because they turned a local Assyrian archive into a global reference point for how we understand myth, scripture, and cultural borrowing.

What it changed: from unique revelation to shared tradition

The Flood Tablet did not “disprove” the Bible, despite what some headlines claimed in the 1870s. What it did was force a change in how scholars framed ancient texts.

First, it showed that the basic elements of the Genesis flood story existed in older Mesopotamian literature: a divine decision to send a flood, a righteous man warned in advance, a large boat, animals preserved, the sending of birds, a sacrifice afterward, and a divine promise or change of heart.

Second, it pushed researchers to look at the Hebrew Bible as part of a wider Near Eastern world. Instead of treating Genesis as an isolated miracle text, scholars began comparing it to Atrahasis, Gilgamesh, and other myths. They noticed similar patterns in creation stories, law codes, and wisdom literature.

Third, it changed public debates. For some religious readers, the tablet was evidence that the flood really happened and that multiple cultures remembered it. For others, it suggested that biblical authors were reworking older myths for their own theological purposes. Either way, the idea of the Bible as a lone, untouched source of stories was gone.

In academic terms, the Flood Tablet helped launch what we now call comparative ancient Near Eastern studies. It encouraged historians to see cultural exchange, borrowing, and adaptation as normal parts of how religions and myths develop.

That shift matters because it moved the conversation from “Is this story unique and literal?” to “How did different societies use similar stories to think about God, justice, and survival?”

Why it still matters: myth, memory, and shared stories

So why are Reddit users still posting about seeing Ashurbanipal’s Flood Tablet in 2026?

Partly because it is a rare case where you can point to a small, physical object and say: this changed how modern people read the Bible. It is not abstract theory. It is a baked lump of clay that forced a rewrite of Western assumptions about scripture and myth.

It also matters because it shows how stories move. The Mesopotamian flood tradition did not stay frozen. It was retold for different audiences, with different gods and morals. By the time the Hebrew authors shaped their own flood story, they were participating in a long-running regional conversation about divine justice and human corruption.

The tablet raises deeper questions that still bother people today. Are religious texts unique revelations, or are they part of a shared human pool of stories? How much of our sacred history is memory of real events, and how much is mythic framing of recurring disasters? What do we do when archaeology digs up a story that looks a lot like one we thought was ours alone?

Finally, the Flood Tablet is a reminder of how fragile cultural memory is. If Ashurbanipal had not hoarded texts, if Nineveh had not burned in a way that baked clay instead of destroying it, if a Victorian engraver had not taught himself cuneiform, the Mesopotamian flood story might have been lost. We would still have Noah, but we would not know he had older cousins.

That matters because it shows that our sense of the past depends on accidents of survival, and that every tablet in a museum case might be waiting to rewrite what we think we know.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Ashurbanipal’s Flood Tablet?

Ashurbanipal’s Flood Tablet is a clay tablet from the 7th century BCE library of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal, found at Nineveh and now in the British Museum. Written in Akkadian cuneiform, it preserves the Mesopotamian flood story that forms part of Tablet XI of the Epic of Gilgamesh, where the survivor Utnapishtim describes building a boat, saving animals, and riding out a divine flood.

Is Ashurbanipal’s Flood Tablet older than the story of Noah’s Ark?

The tablet itself dates to the 7th century BCE, but it preserves a flood story that is based on even older Mesopotamian traditions such as Atrahasis and the Sumerian Ziusudra tale, which likely go back to the early second millennium BCE or earlier. The final form of the Genesis flood story is generally dated later than these Mesopotamian texts, so the tradition recorded on the Flood Tablet is older than the biblical version.

Did the Bible copy the flood story from the Epic of Gilgamesh?

Most scholars think the biblical flood story and the Mesopotamian versions share a common cultural background rather than a simple word-for-word copying from one tablet. Hebrew authors were part of the same Near Eastern world where flood myths were well known. They likely knew older traditions and reshaped them to express their own theology about one God, human sin, and covenant, so the relationship is one of adaptation and shared tradition, not straightforward plagiarism.

Where can I see Ashurbanipal’s Flood Tablet today?

The most famous Flood Tablet from Ashurbanipal’s library, usually identified as Tablet XI of the Epic of Gilgamesh, is held by the British Museum in London. It is often on display in the Mesopotamian galleries, though specific objects can rotate in and out of exhibition. The museum’s online collection also has high-resolution images and translations for those who cannot visit in person.