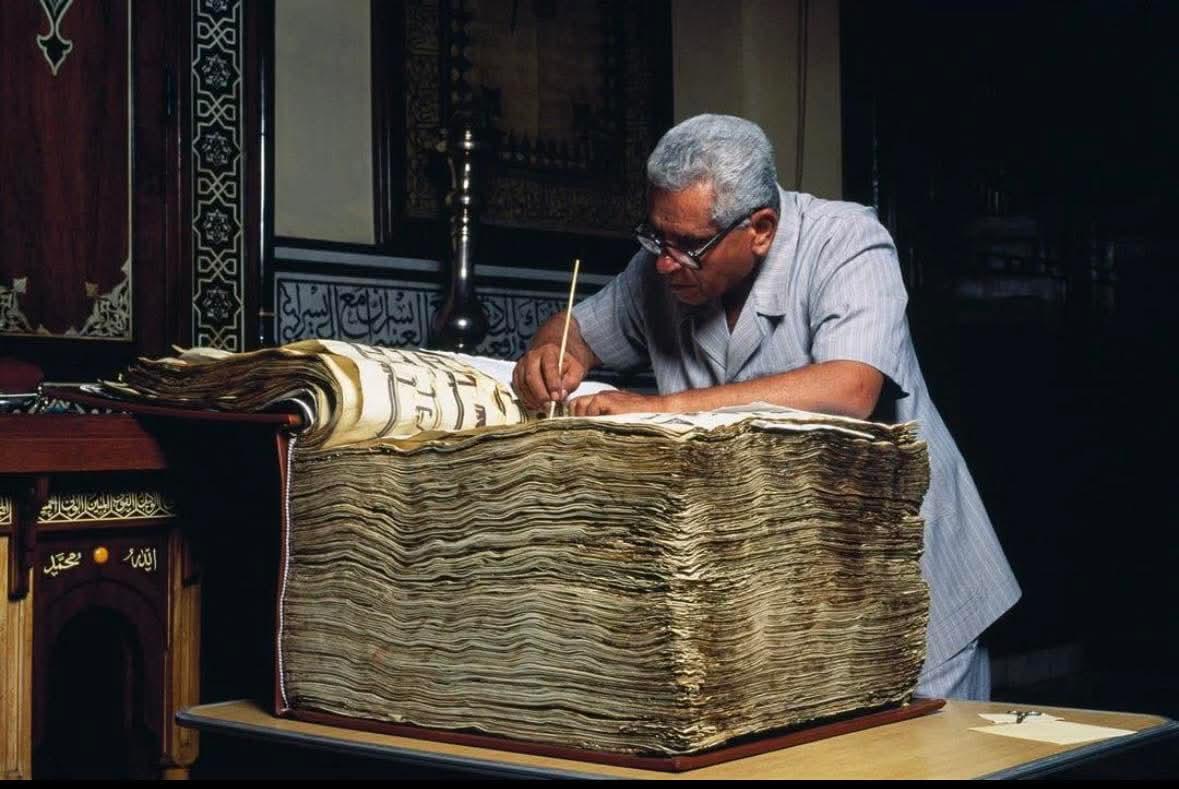

In a conservation lab in Egypt, a team in white coats lifts a single page with both hands. The leaf is almost as big as a small table, thick as leather, and heavy enough that one person struggles to move it. It is a page from an 8th‑century Quran manuscript, one of about 1,087 surviving leaves that together weigh around 80 kilograms. Each leaf was made from the skin of a whole animal.

To a modern eye, this giant Quran looks oddly familiar. If you have seen photographs of medieval European Bibles or choir books, you might think: same size, same creamy animal skin, same dense columns of script. They look similar because both Islamic and Christian scribes, a thousand years ago, solved the same problem with the same technology: how to turn animal bodies into massive books meant to last and to impress.

An early Quran manuscript is a handwritten copy of the Quran, usually on parchment, produced in the first centuries of Islam. A medieval Bible manuscript is a handwritten copy of the Christian scriptures, often in Latin, created in European scriptoria. Both were made before printing, by teams of specialists, for rulers, churches, and mosques.

By the end of this story, the similarities start to look less like coincidence and more like two civilizations wrestling with the same questions: how do you materialize the word of God, and who gets to control it?

Why did early Qurans and medieval Bibles start as giant animal-skin books?

The 8th‑century Quran being restored in Egypt did not appear out of nowhere. It belongs to the first wave of large-format Qurans produced under the early Islamic empires, probably the late Umayyads or early Abbasids. Scholars debate the exact origin of this specific manuscript, but many comparable codices come from Iraq, Syria, or Egypt between the late 7th and 9th centuries.

At roughly the same time, in Latin Christendom, the Bible was also becoming a single, bound volume. Earlier Christian communities used scrolls and smaller codices, but by the 8th to 12th centuries, monasteries and cathedrals were commissioning gigantic Bibles and choir books. Think of the Codex Amiatinus in the early 8th century or the 12th‑century giant Bibles of northern Europe.

The shared starting point was technology. Both worlds used parchment, which is processed animal skin. Paper existed in China and was just beginning to move west, but in the 700s and 800s, if you wanted a durable book in the Mediterranean or Europe, you used animals.

For the Egyptian Quran, each leaf reportedly used one whole animal skin. Multiply that by 1,087 leaves and you are looking at the bodies of more than a thousand animals, probably sheep or goats. A single large medieval Bible might use the skins of 200 to 300 animals. In both cases, the book was not just a text. It was a massive investment of livestock, labor, and time.

There is also a political story. Early caliphs wanted monumental Qurans to project power and piety. Huge Qurans were sent to major mosques in cities like Damascus, Kairouan, and perhaps Fustat in Egypt. Christian rulers and abbots did the same. A giant Bible on the high altar of a cathedral was a statement about wealth, orthodoxy, and status.

So what? The fact that both traditions began with enormous, resource-hungry codices tells you that sacred books were not just for reading. They were instruments of authority, built big enough to be seen, revered, and controlled.

How were Qurans and Bibles physically made from animals?

Turn one of those 8th‑century Quran leaves in the lab and you are looking at the end of a long production line. First, animals were slaughtered. Their skins were soaked in lime to loosen hair and flesh, then stretched on frames and scraped with curved knives. The goal was a smooth, thin, durable sheet. This process was nearly identical in Islamic lands and Christian Europe.

For a giant Quran or Bible, parchment makers had to be consistent. A codex with over a thousand leaves needed sheets of similar thickness and size. That meant skilled craftsmen and a steady supply of animals. In both worlds, parchment production often clustered around cities, monasteries, or state centers where demand was high.

Once the parchment was ready, scribes took over. Early Qurans like the one in Egypt used scripts such as Kufic. Letters are angular, horizontal, and widely spaced. Early copies often had minimal or no vowel marks, which suggests they were meant for people who already knew the text orally. Medieval Bibles used scripts like Carolingian minuscule or later Gothic hands, more compact and filled with abbreviations to save space.

Both traditions ruled the page with a stylus or ink to create lines. Both used black or brown ink made from soot or iron gall. Both sometimes used red ink for headings or important words. The difference is in decoration. Many early Qurans avoided figurative imagery and instead used geometric patterns, vegetal motifs, and gold to mark verse divisions and surahs. Medieval Bibles often included figurative illuminations, decorated initials, and marginal scenes with humans and animals.

There is a modern misconception that early Qurans were plain and early Bibles were lavish. In reality, both could be austere or richly decorated, depending on patron and context. Some early Qurans are heavily ornamented with gold and colored inks, while some monastic Bibles are visually restrained.

So what? The shared craft of turning animal skin into pages, and ink into sacred text, meant that across religious lines, book makers were solving the same practical problems. The differences in script and decoration reflect theology and taste, but the underlying technology was a common Mediterranean and European toolkit.

Who made them, and under what working conditions?

One of the hidden similarities is the human chain behind each page. The 8th‑century Quran in Egypt was almost certainly not the work of a lone genius. Large Qurans were usually collective projects, involving parchment makers, ruling authorities, scribes, and sometimes illuminators.

In the early Islamic world, scribes worked in settings that ranged from court-sponsored scriptoria to mosque-related workshops and private copyists. The Quran had to be copied with extreme care. Errors were corrected by scraping off ink with a knife and rewriting. Some projects may have had a supervising scholar to check accuracy.

In medieval Europe, monasteries were the main centers of production until urban workshops took over in the later Middle Ages. Monks and later professional scribes copied the Bible line by line, often in silence, sometimes in large rooms with multiple desks. The work could be tedious and physically hard. Marginal notes in some manuscripts complain about cold fingers, tired eyes, and long hours, though we do not have such personal notes in early Qurans.

Both traditions had to train scribes for years. Script was not just handwriting. It was a disciplined art with rules about letter forms, spacing, and layout. In Islamic culture, calligraphy gained a special status as the primary visual art in religious contexts. In Christian Europe, illumination and figurative painting often took that role, but script still mattered.

There is a modern fantasy that these books were made in some mystical atmosphere. In reality, they were also workplaces. People were paid, deadlines existed, and mistakes happened. Some Qurans and Bibles show corrections, erasures, and changes in hand where one scribe stopped and another took over.

So what? Seeing the Quran and the Bible as products of organized labor, training, and quality control makes them less abstract. It reminds us that sacred texts, before they were theology, were day jobs for real people whose skills shaped what survived.

How were these giant Qurans and Bibles actually used?

Here is where size really matters. A codex weighing 80 kilograms is not a personal devotional book. The 8th‑century Quran in Egypt, like other massive Qurans, was probably kept in a mosque or major religious complex. It may have been placed on a large stand and used for ceremonial readings, or simply displayed as a symbol of piety and power.

Islamic practice relied heavily on memorization and oral recitation. Many believers knew large portions of the Quran by heart. So a monumental Quran functioned less as a practical reading copy and more as an authoritative reference and prestige object. Smaller Qurans, sometimes on paper by the 10th century, circulated more widely for study and personal use.

Medieval giant Bibles and choir books had a similar public role. A huge Bible might sit on the lectern in a monastic choir or cathedral, used when a lector read aloud to the community. Large antiphonaries and graduals, containing liturgical chants, were made so that several singers could read from one book at a distance.

Like the big Qurans, these volumes were not meant to be tucked under an arm and taken home. They were communal objects, tied to specific spaces and rituals. Smaller, more portable Bibles and Gospel books existed alongside them for study, preaching, and travel.

There is a misconception that because these books are so big, people in the past must have been physically reading from them all the time. In reality, much of religious life was oral and aural. The book anchored the ritual and symbolized authority. The words themselves often lived in memory and voice.

So what? The way these codices were used shows that their main job was not convenience. It was to embody sacred text in a way that was visible, communal, and hard to tamper with.

What happened when paper and printing arrived?

The 8th‑century Quran being restored in Egypt belongs to a parchment world. That world did not last forever. By the 9th century, paper technology, learned from China, spread through the Islamic world. Cities like Baghdad and later Cairo became centers of paper production. Qurans began to be copied on paper, which was cheaper and lighter than parchment.

This shift had consequences. Paper made it easier to produce more copies, in more sizes, for more people. The Quran moved from being primarily a monumental, elite object to something that could exist in many households and schools. Parchment Qurans did not disappear overnight, but paper gradually took over for everyday use.

In Christian Europe, paper arrived later, in larger quantities from the 13th century onward. The real shock came with printing in the mid‑15th century. Gutenberg printed a Latin Bible on paper and some parchment. Within decades, printed Bibles were circulating in numbers unimaginable for a manuscript culture.

The Islamic world adopted printing more slowly for religious texts. There were technical, economic, and religious reasons, including concern about errors in the Quran if printed mechanically. Large-scale printing of Qurans in the Muslim world took off mainly in the 19th century, though there were earlier printed editions in Europe and limited Ottoman experiments.

So what? The move from parchment to paper, and from hand copying to printing, turned both the Quran and the Bible from rare, heavy objects into texts that could saturate societies. The giant animal-skin codices became relics of an earlier information regime.

Why restore an 80 kg Quran today, and why does it echo medieval Bibles?

Back in that Egyptian lab, conservators clean, flatten, and repair the 8th‑century Quran’s leaves. They stabilize flaking ink, mend tears with fine Japanese paper, and store each leaf in climate-controlled boxes. Similar scenes play out in European libraries, where conservators work on medieval Bibles and choir books.

Modern viewers often ask the same questions when they see photos of these books online. How many animals did this take? Why make it so big? Was this wasteful? The answers are shared across religious lines. These books were expensive because they were meant to last and to project seriousness. In societies where livestock were wealth, turning hundreds of animals into a single book was a statement about what mattered most.

They also raise ethical questions today. Some people are uncomfortable with the sheer number of animals used. Others see them as historical facts from a world where animal labor and products were woven into daily life. Conservation work does not undo that history, but it does keep the evidence accessible.

The visual similarity between an 8th‑century Quran leaf and a 12th‑century Bible page is not accidental. Both are products of the same basic constraints: no printing, no cheap paper, and a desire to fix sacred words in a durable, impressive form. The scripts differ, the languages differ, the theology differs. The engineering problem was the same.

So what? Restoring these massive codices, and noticing how they resemble each other, reminds us that before religions argued about doctrine, their followers often used the same tools and materials to solve the same practical problem: how to give the word of God a body that could survive a thousand years.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why are some ancient Qurans so large and heavy?

Some early Qurans, like the 8th‑century manuscript in Egypt, were made as monumental copies for mosques or rulers. Using parchment from whole animal skins created huge, durable leaves. These codices were prestige objects and ceremonial references, not personal reading copies.

How many animals were used to make a medieval Bible or Quran?

Exact numbers vary, but a large parchment Bible might use the skins of 200–300 animals. The 8th‑century Quran in Egypt has about 1,087 leaves, reportedly each from one animal, so more than a thousand animals. Parchment was expensive, which is why such books were rare and elite.

What is the difference between parchment and paper in old religious books?

Parchment is made from animal skin, processed and stretched into sheets. It is strong and long-lasting but costly. Paper is made from plant fibers and rags, much cheaper to produce. Early Qurans and Bibles used parchment, then gradually shifted to paper as it became available and affordable.

Did people actually read from these giant Qurans and Bibles?

They were used, but not like modern personal books. Giant Qurans and Bibles were kept in mosques, monasteries, and cathedrals. They were used for ceremonial readings and as symbols of authority. Everyday study and devotion relied more on memory, oral recitation, and smaller, more portable manuscripts.