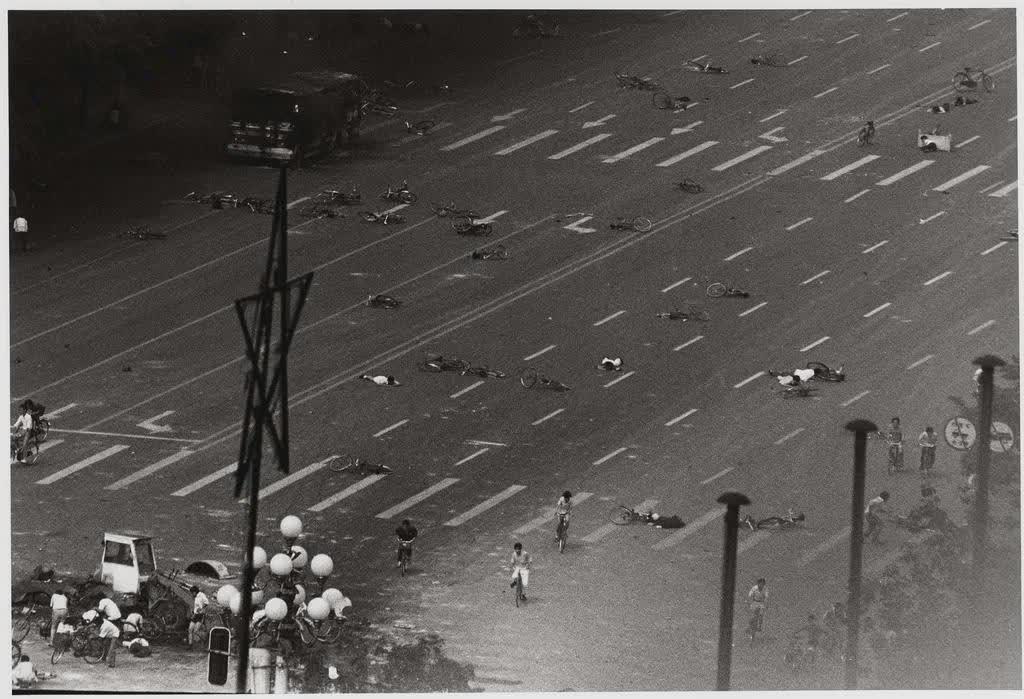

In the photograph, the square is almost empty. The crowds are gone. The banners are gone. What is left are bodies, burned-out vehicles, scattered belongings, and soldiers. Hong Kong photographer Kan Tai Wong took that image in Beijing in June 1989, then smuggled the film out of China. The Chinese state wanted the world to remember nothing. His camera made sure the world remembered something.

The Tiananmen Square massacre of June 3–4, 1989, was the violent end of a weeks-long student-led protest movement in Beijing. Troops of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) fired on civilians and cleared the square and surrounding streets. Hundreds, possibly thousands, were killed. The aftermath was not just physical wreckage. It was a political reset for China, a media blackout, and a long campaign of forgetting.

Tiananmen Square refers both to the protest movement in spring 1989 and to the massacre that ended it. The massacre was a military crackdown ordered by top Chinese leaders to crush a broad pro-democracy and anti-corruption movement in Beijing. It changed how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) handled dissent and how the world dealt with China.

Why were there protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989?

The story does not start with tanks. It starts with inflation, corruption, and a funeral.

In the 1980s, China was changing fast. Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms had opened the country to markets and foreign investment. Growth was real, but so was pain. Prices rose sharply. State jobs felt less secure. Party officials and their relatives made money through connections. Ordinary people watched the new winners and smelled corruption.

Inside the Communist Party, there was a debate. Reformers like General Secretary Hu Yaobang were open to political loosening: more tolerance for criticism, some space for intellectuals and students. Conservatives feared that loosening would unravel one-party rule. Hu was pushed out in 1987 for being too soft on student protests.

On April 15, 1989, Hu Yaobang died. Students in Beijing began gathering in Tiananmen Square to mourn him. The mourning quickly turned political. Wreaths and elegies turned into posters and petitions. Students called for press freedom, action against corruption, and dialogue with leaders. They did not start out demanding the end of Communist rule. They wanted the Party to live up to its own promises.

By late April, thousands of students were in the square. They marched to the Great Hall of the People. They issued lists of demands. On April 26, the People’s Daily published a front-page editorial, likely approved by Deng Xiaoping, calling the protests “turmoil” and hinting at a threat to the socialist system. That word, turmoil, enraged students. The crowd grew.

In May, workers, journalists, and residents joined. A hunger strike by students before a state visit by Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev embarrassed the leadership. Television broadcast images of frail students on hospital beds, and Beijing residents brought food and money. The square became a camp, part festival, part political forum, part pressure point on the Party.

The protests mattered because they exposed a split inside the leadership and showed that, for a few weeks, public opinion in the capital could shape national politics.

Who ordered the crackdown and why did it turn violent?

Inside Zhongnanhai, the walled leadership compound near Tiananmen, the mood was the opposite of the square’s carnival atmosphere. Deng Xiaoping, though retired from formal office, still held ultimate power. Premier Li Peng and other hardliners argued that the protests threatened the Party’s survival. General Secretary Zhao Ziyang, Hu Yaobang’s successor, favored negotiation and caution.

On May 20, 1989, the government declared martial law in parts of Beijing. Troops tried to enter the city but were blocked by residents who talked to them, argued with them, and physically obstructed their trucks. For a brief moment, it looked as if public resistance might stop the army.

That moment ended when Deng and the hardliners decided to use force. Internal records and later memoirs suggest that Deng approved the use of live ammunition to clear the streets. Zhao Ziyang opposed this. On May 19, he went to the square, spoke to students through a loudspeaker, and reportedly said, “We have come too late.” It was his last public appearance. He was purged and placed under house arrest.

On the night of June 3 and into the early hours of June 4, PLA units advanced from several directions toward Tiananmen Square. They used live fire. Residents built barricades, set buses on fire, and tried to stop the convoys. Soldiers shot into crowds. Most of the killing happened on the approach roads, especially along Chang’an Avenue and in western Beijing, not in the square itself.

The exact death toll remains unknown. The Chinese government once mentioned around 200–300 dead, including soldiers. Other estimates from hospitals, diplomats, and human rights groups range from several hundred to over a thousand. The record is unclear because the state has never allowed a full investigation.

By the early morning of June 4, troops had reached the square. Student leaders negotiated a withdrawal. Many students left the square in the pre-dawn hours, walking out between lines of soldiers. Some accounts suggest that there was sporadic firing in the square itself, others that the main killing had already happened in the streets. What is certain is that by daylight, the occupation was over and the army controlled the center of Beijing.

The decision to use the army against civilians mattered because it set a line: the Party would protect its monopoly on power with lethal force if necessary.

What did the aftermath in Tiananmen Square actually look like?

This is where Kan Tai Wong’s photograph comes in. The world knows the “Tank Man” image, taken on June 5, showing a lone man blocking a line of tanks. Far fewer people have seen the wide shots of the wreckage and the bodies.

After the crackdown, the authorities moved quickly to clean up the center of Beijing. Burned vehicles were towed away. Bloodstains were washed from the streets. Debris was cleared. But before the cleanup was complete, some photographers, including Wong, captured the raw aftermath: charred buses, twisted bicycles, abandoned shoes, and corpses covered with sheets or left exposed.

Wong was a Hong Kong photographer, working in a city that still had a free press in 1989. He took his film out of mainland China secretly, knowing that if it were discovered, the images would be confiscated and he could be arrested. Other foreign journalists hid rolls of film in clothing, smuggled them through airports, or passed them to couriers.

The Chinese government tried to control the narrative. Domestic media spoke of a counterrevolutionary riot. State television showed injured soldiers and burned military vehicles, not dead civilians. Foreign journalists were harassed, beaten, or expelled. Cameras were smashed. Film was seized.

Yet enough images escaped. They showed not only the famous standoff with tanks but also the scale of the violence. Hospital corridors filled with wounded. Families searching for relatives. Streets littered with shell casings. Those photographs ran on front pages around the world.

The visual record of the aftermath mattered because it contradicted the official story and fixed the reality of mass killing in public memory outside China.

How did the Chinese state erase and rewrite Tiananmen at home?

After the shooting stopped, the political cleanup began. The Party called the protests a “counterrevolutionary rebellion.” It launched arrests of student leaders, worker organizers, and anyone suspected of helping the movement. Some were tried and sentenced to long prison terms. Others fled China through underground networks that activists later nicknamed the “underground railroad” to Hong Kong and beyond.

Inside the Party, Zhao Ziyang was removed as General Secretary and placed under house arrest for the rest of his life. His allies were demoted or purged. Hardliners gained influence. The message to officials was clear: political reform that threatened Party control was off the table.

Censorship tightened. Books, films, and articles about the protests were banned. Discussion of June 4 became dangerous. Families of victims were monitored. The group “Tiananmen Mothers,” formed by relatives of those killed, was harassed and blocked from public mourning.

In the 1990s and 2000s, as the internet arrived in China, the state adapted. Keywords like “Tiananmen,” “June 4,” and even coded references like “64” were filtered. Social media posts about the massacre were deleted within minutes. Users who persisted could lose accounts or face police visits. School textbooks mentioned 1989, if at all, in vague language about “political turmoil.”

Many younger Chinese today know little or nothing about what happened. Some have heard rumors from parents or relatives. Some have seen glimpses through VPNs or foreign travel. But the state’s long campaign of silence has been effective inside the country.

The erasure mattered because it showed how the Party would pair physical repression with long-term control of memory to prevent a shared narrative of resistance from forming.

How did the world react to the Tiananmen Square massacre?

Outside China, the reaction in 1989 was swift and angry. The images of tanks rolling into a capital city and soldiers firing on unarmed civilians shocked audiences that had grown used to seeing China as a country cautiously reforming.

The United States, European countries, and others imposed sanctions. Arms sales to China were restricted. Some loans and high-level contacts were frozen. Western leaders condemned the crackdown in strong language. Chinese students abroad were allowed to extend their stays or seek asylum in countries like the United States, Canada, and Australia.

Yet the sanctions did not last forever. By the early to mid-1990s, many governments were re-engaging with Beijing. China’s huge market and its role in regional stability mattered. Deng Xiaoping’s “southern tour” in 1992 revived economic reform and reassured foreign investors that China would keep opening its economy, even if its politics stayed tightly controlled.

Human rights groups and some politicians kept June 4 alive as an issue. Annual vigils in Hong Kong’s Victoria Park, which began in 1990, drew tens of thousands of people. They held candles, read the names of the dead, and demanded accountability. For years, Hong Kong was the only Chinese city where such a public commemoration was legal.

The international reaction mattered because it showed the limits of global pressure. The world protested but then adjusted to a China that was both an economic partner and a one-party state that had used lethal force against its own citizens.

How did Tiananmen change China’s path after 1989?

Inside China, the lesson that the leadership took from 1989 was not “never again use force.” It was “never again lose control.”

Politically, the Party doubled down on one-party rule. It strengthened internal security organs, from the police to state security agencies. It invested in surveillance and neighborhood-level monitoring. Later, with digital tools, this grew into one of the most sophisticated systems of domestic control in the world.

Economically, the Party made a bargain with the public: you stay out of organized politics, and we will deliver rising living standards. Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour in 1992 signaled that market reforms were back on. Special Economic Zones expanded. Foreign factories moved in. Millions left the countryside for city jobs.

The Party also learned to manage dissent differently. Instead of letting a single protest center grow in the capital for weeks, authorities moved to nip local protests in the bud. Grievances about land seizures, pollution, or labor conditions were sometimes addressed with targeted concessions, sometimes with quick arrests, but rarely allowed to coalesce into a national movement.

For the military, Tiananmen was a trauma and a turning point. The PLA had been ordered to fire on civilians in the capital, something many soldiers found shocking. In the years after, the Party worked to tighten political control over the army and to professionalize it. The message was that the PLA existed first to protect the Party, then the country.

The shift after 1989 mattered because it produced the model of “authoritarian capitalism” that defines the People’s Republic of China today: rapid economic growth under a Party that tolerates almost no organized political challenge.

Why do photos like Kan Tai Wong’s still matter today?

Three decades later, the Chinese state has largely succeeded in suppressing public memory of June 4 inside the mainland. But it has not erased the global record. Images like Kan Tai Wong’s aftermath photo are part of that record.

They matter for several reasons. First, they document what the Chinese government denies. When officials call 1989 a “necessary action” against “turmoil,” the photographs show the cost in human bodies and burned streets.

Second, they remind us that Tiananmen was not just a single dramatic moment of a man facing tanks. It was a broad movement, a violent crackdown, and a physical and political cleanup. The empty, wrecked square after the troops moved in is as much a part of the story as the crowded, hopeful square in May.

Third, they speak to a wider pattern: authoritarian regimes fear uncontrolled images. That is why photographers in Beijing in 1989 were beaten and arrested, why film was confiscated, and why some, like Wong, had to smuggle their work out. Every surviving frame is a small defeat for censorship.

Finally, these images keep pressure on the question that the Chinese state has never answered: who was killed, how many, and on whose orders. The Tiananmen Mothers still ask for a public accounting. Exiled student leaders still speak about those nights. Foreign archives still hold documents that have not been fully opened.

The survival and circulation of photographs from the aftermath of Tiananmen matter because they keep an uncomfortable fact alive: China’s modern rise rests in part on a decision in 1989 to crush, not accommodate, a mass call for political change.

What is Tiananmen’s legacy in China and beyond?

Tiananmen’s legacy is not a single thing. For China’s rulers, it is a warning about the dangers of political loosening. For many Chinese citizens who remember it, it is a source of quiet anger or grief. For younger generations inside China, it is often a blank space filled with rumors or foreign clips.

Outside China, Tiananmen has become shorthand for state violence against peaceful protest. It is invoked when tanks roll into cities, when governments shut down squares, when internet blackouts hide crackdowns. The “Tank Man” image and the lesser-known aftermath photos circulate whenever people ask whether economic development leads inevitably to democracy.

There is another legacy too. Tiananmen shaped how the world talks about doing business with authoritarian regimes. In 1989, many believed that trade and investment would gradually soften China’s politics. After decades of engagement and no political liberalization, that belief looks more like wishful thinking. The memory of June 4 sits in the background of current debates about human rights, supply chains, and sanctions.

In Hong Kong, the legacy has taken a sharp turn. For years, the city’s annual Tiananmen vigil kept the memory alive in Chinese. After Beijing imposed a new national security law in 2020, the vigil was banned. Organizers were arrested. Statues and memorials were removed. The space for public remembrance inside Chinese territory has shrunk.

Yet the images survive. Smuggled film, foreign broadcasts, and eyewitness accounts have built a record that is hard to erase. As long as those photographs are seen, the official silence is incomplete.

Tiananmen’s legacy matters because it marks the moment when China’s leadership chose a path of economic opening without political reform, and because the visual evidence of that choice keeps challenging the story the state tells about itself.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly happened in the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989?

In spring 1989, students and citizens in Beijing gathered in Tiananmen Square to mourn reformist leader Hu Yaobang and to call for political reform, press freedom, and action against corruption. After weeks of protests, China’s leaders declared martial law. On the night of June 3 and early June 4, the People’s Liberation Army moved into Beijing using live ammunition to clear protesters and residents from the streets leading to Tiananmen. Hundreds, possibly more than a thousand, were killed, mostly on the approach roads to the square. The army then occupied the area and the government labeled the movement a counterrevolutionary riot.

How many people were killed at Tiananmen Square?

The exact number of people killed in the Tiananmen Square crackdown is unknown and remains classified by the Chinese government. Official Chinese figures once suggested around 200–300 deaths, including soldiers. Independent estimates based on hospital reports, eyewitness accounts, and diplomatic cables range from several hundred to over a thousand. Most victims were killed on the streets leading to the square, not in the square itself. Because the authorities blocked investigations and controlled information, historians can only give a range, not a precise figure.

Why are photos of the Tiananmen Square aftermath, like Kan Tai Wong’s, so rare?

Photos of the Tiananmen Square aftermath are rare because Chinese authorities tried to prevent any independent record of the violence. During and after the crackdown, police and soldiers confiscated film, smashed cameras, and harassed or expelled foreign journalists. Domestic media were ordered to show only images that fit the official narrative of a suppressed “riot.” Photographers like Hong Kong’s Kan Tai Wong had to hide their film and smuggle it out of mainland China. The few surviving images of burned vehicles, bodies, and wreckage exist because some photographers managed to evade censorship and get their work to foreign media.

How does the Chinese government treat the memory of Tiananmen Square today?

The Chinese government treats the 1989 Tiananmen protests and massacre as a highly sensitive topic. It bans public commemorations on the mainland, censors references to June 4 and related terms in media and online platforms, and restricts academic and journalistic work on the subject. School textbooks mention 1989 only briefly, if at all, usually in vague terms about “political turmoil.” Families of victims and groups like the Tiananmen Mothers face surveillance and pressure when they seek accountability. For years, Hong Kong held large public vigils, but those have been banned since the imposition of the national security law in 2020.