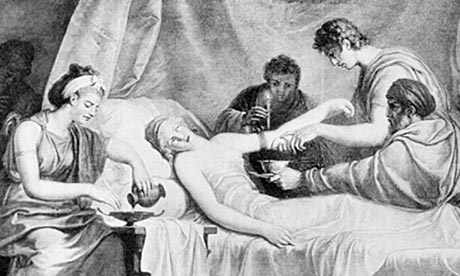

Photo: WND

History is a story we tell ourselves about the past, mostly to make sense of the present. Unfortunately, those stories aren’t always quite factual.

Sometimes we need to simplify the past in order to help people understand it. Sometimes we want to justify the mistakes of the past instead of acknowledging them. Sometimes something is so funny, exciting, or satisfying that a little thing like the truth can’t get in the way. Whatever the reason, there’s no end to the Grade-A hooey that’s made its way into the collective memory, and even into textbooks and classrooms. Here are a few of the most popular misconceptions:

Photo: Gomerblog

1. People generally died younger in the past.

We’ve all heard this one: a person in previous centuries with an otherwise good life could only expect to live until he or she was in their 30s or 40s. Mid-life crises occurred around 17, and a 35 year old could expect a senior discount at local businesses with Ye Olde AARP card. Everyone from prehistory to Roman times to colonial times was doomed to clock out at an age when most modern people are just getting into yoga.

The root of this myth is a misunderstanding of statistics. “Life expectancy” as an average age of death among humans in various populations really was much lower. However, this isn’t because adults died young. It’s because children died often.

Before the technological and medical advances of the 20th century, infants and children died pretty regularly. They were just far more vulnerable to the pre-industrial (and early industrial) dangers that lurked around every corner, from disease to malnutrition to pissed-off bears. Their early deaths, when calculated into the overall average, dragged the stats down in a very misleading way. Yes, a 2-year old had a far tougher time surviving to adulthood—but if he did, he was likely to live into his 60s or 70s or beyond, just as we do now.

2. Columbus proved that the world was round.

This one is still making the rounds in classrooms across America. As the story goes, Europe was desperate for a convenient shipping route to Asia. Columbus had an idea: that the Earth was spherical, and to sail west around it would lead one to the Eastern shores of the Orient. Europeans, we’re told, believed that the Earth was flat, and that Columbus was crazy. He went from monarch to monarch, laughed out of courts across the land until the Spanish royals finally took a gamble on his wacky theory. A few months later, Columbus bumped into the New World.

There’s only one problem with this story: Europeans already knew that the Earth was round. Europeans had known that the Earth was round for a very, very long time (think of the ancient Greek images of Atlas holding up the clearly spherical world).

Columbus wasn’t laughed from court to court because he was wrong about the shape of the Earth; he was wrong about the size of the Earth. Leading scholars had calculated the size of the planet with impressive accuracy, but Columbus was convinced by a “small Earth” theory that had been making the rounds—proving that people don’t need the Internet to be misled by junk science. By those calculations, Asia should’ve been right where the Americas actually were.

The “flat-earth” myth comes from a fictionalized account of the Columbus story by Washington Irving, which leaked its way into popular belief and eventually into school curricula.

Photo: History.com

3. The “Boston Massacre” was a massacre.

The Boston Massacre is thought of as an infamous atrocity, a slaughter of innocent colonists by British soldiers that helped to spur the American Revolution. Paul Revere’s famous drawing of the incident depicts woeful Americans collapsing under the fire of cold-eyed Regulars, red-coated murderers who represented all that was wrong with British rule.

Paul Revere was wrong. In fact, Paul Revere wasn’t even there. His misleading portrayal of the event conflicts with all known testimony, including the testimony given at the soldiers’ trial (in which they were defended by John Adams, unquestionably an American patriot and not given to excessive sympathy for the British).

In truth, the colonists in question were a drunk-and-pissed-off rabble who had surrounded the soldiers and thrown various objects at them, repeatedly screaming at the soldiers to “Fire!” if they dared. After one of the soldiers was struck down by an unknown flying object, he recovered his musket and fired without being given the order, leading several other soldiers—confused by the shot and the repeated shouting of the word “fire” from various directions— to do the same. 5 Americans died, hardly a “massacre” by military standards.

Thanks to Adams’ strong defense, the soldiers were mostly exonerated. Two of them had their thumbs branded as punishment for manslaughter, but the final ruling was that generally, the Americans were in the wrong. Regardless, Revere’s propaganda spread through the colonies faster than the speed of truth, and the Revolution picked up steam.

Photo: legalinsurrection.com

4. Paul Revere’s ride.

Most American schoolkids have had another Revere-related false image planted in their heads by well-meaning but misinformed teachers: that of himself tearing through Lexington and Concord on horseback screaming “The British are coming!” Following lantern-based intel, or so the story goes, the revolutionary rode around Massachusetts raising a ruckus to prepare his fellow patriots for the first battle of what would become the American Revolution.

Except it never happened. This is another case of exciting fiction being mistaken for history. In this case it’s Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s patriotic poem “Paul Revere’s Ride.” Revere did in fact engage in a mission to prepare his fellow patriots for a British incursion, and he was a key figure in the underground insurgent/terrorist group known as the Sons of Liberty. But the notion of his riding around waking the neighbors with his warning is silly for several reasons.

First, they were all “British,” including Revere. At that point, the SOL’s movement was about demanding colonists’ rights as British citizens, not independence or the creation of a new nation. To yell that “the British [were] coming” would make about as much sense as yelling that the Earthlings were coming. Second, not everyone in town was on Revere’s side. In fact, it’s generally accepted that only about a third of the colonists ever supported the Revolution, so loudly announcing your secret organization’s rebellious intent wouldn’t have been the brightest move. Really, Revere quietly warned specific, trusted Sons of Liberty of the approaching British “regulars.”

Revere also wasn’t alone; two other riders went out on the same covert mission. Their work was crucial to the preparation of Lexington and Concord’s defenses and the fomenting of the Revolution, but it’s a darn good thing that Revere wasn’t as indiscreet as people today imagine.

Photo: The Economist

5. The United States was founded as a “democracy.”

Democracy is an oft-misused term, not least when it’s applied to the American Revolution. The Revolution was about a lot of things: taxes, human equality, Enlightenment principles, and the problems inherent in monarchy. But the notion that the Founding Fathers tried to create a nation in which “the people” make the decisions couldn’t be more mistaken. Instead, they founded a Republic, meant to be guided by Constitutional principles rather than the will of what John Adams called “the mob.”

Originally, the popular vote didn’t even factor into the election of the President, at least not in most states. The Constitution only requires that states choose electors to choose the President. How they’re chosen, and how they vote, is up to the state to figure out. Only 6 of the original 13 states bothered to solicit public opinion in early elections.

Presidential candidates didn’t even bother to campaign, because it really didn’t matter how popular you were (Even today, the popular vote is occasionally overridden, as in the Bush/Gore fiasco of 2000). Nor did the people elect members of the Senate; they too were appointed by state governments. The only job in the federal government one could get with the support of the crowd was a seat in the House of Representatives, or “lower” House of Congress.

On top of all that, most people couldn’t vote anyway! Non-landowners, to say nothing of minorities and women, were excluded from the body politic. That meant that only middle-to-upper class white men had any input at all, and that mostly at the local and state level. Fear of the “tyranny of the majority” was enough to convince the Founders that “the people” should have a very, very limited say in national affairs. It was only after the populist movements of early Democrats, along with the eventual enfranchisement of women and people of color, that the majority became a force to contend with in American politics.