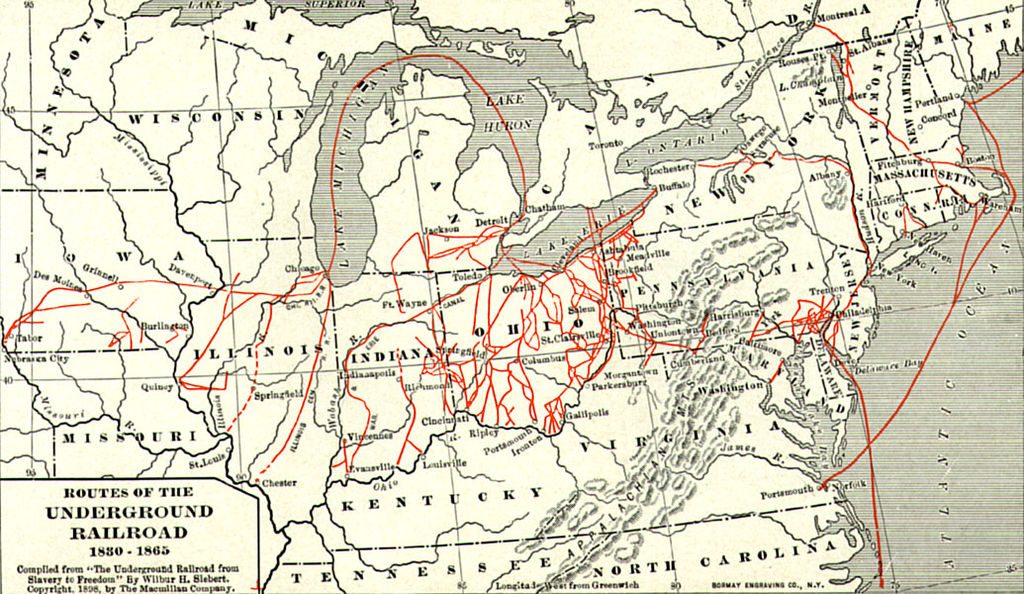

During the nineteenth century, slaves would use the Underground Railroad, a network of safe houses and secret routes, to escape to Canada or free states. People sympathetic to their cause, such as abolitionists or other freed slaves, would aid them in escaping and getting to safety. An estimated 100,000 slaves escaped to freedom using the Underground Railroad from 1810-1850, though it was used most in the 1850s and 60s. Ontario, which was a part of British North America, was perhaps the most popular destination for escaped slaves, as all slavery was prohibited.

As early as the 1780s, George Washington had made comments on Quakers using some system of the Underground Railroad to aid fugitive slaves. Not until the 1830s did the Underground Railroad become more known and used. When the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was passed, it was made a law that officials from free states were still required to assist slaveholders in finding and capturing their escaped slaves. Many people from free states, including governmental figures, did not follow the law, and some would aid slaves in their escapes. However, in 1850 another act was passed that made it so that all officials and people from free states had to help slave owners capture their slaves. It was not uncommon for free blacks to be captured either because the law did not require many documents to show that a person was freed or a slave. Judges in court were even paid higher if they confirmed a suspect was a slave, even if they were actually not.

Though it was called the Underground Railroad, the escape routes used were not underground, nor were they a railroad. Specific homes and businesses would aid them and let them sleep and ear. These were called “stations” and “depots” and the home or business owners were called “station masters”. If they were able to contribute money or other goods, then they were called “stockholders”. The person who guided and were responsible for moving the fugitives were the “conductors”.

First, escaping slavery was not easy, and was the most difficult part. By the time they were able to reach a home to stay in, they had already completed the hardest part of the task. Nothing about using the Underground Railroad or escaping slavery safely in general was easy though. Only a small fraction of slaves were ever able to escape. After they escaped, often by a “conductor” entering a plantation disguised as a slave, they would travel 10-20 miles by foot to the next station at night. It was far too dangerous to travel in daylight because there was a higher chance of being seen and caught. Groups would usually be small, though occasionally they would be between 15-20, but never more than that. Once they reached a station, they would be fed and have a chance to rest after spending a long time traveling. As the fugitives arrested at each station, a message would be sent to the next one to alert them that a group was on their way.

Occasionally, they would even travel by train, boat, or wagon. To do this though, they would need enough money for passage, and money to buy new clothing. If a black person, whether they were free or not, was in tattered clothing, it would draw suspicion. Individuals and groups who supported and were sympathetic to the cause would donate money for this reason. In some Northern cities such as New York, Philadelphia, and Boston, vigilance committees were formed. They would donate money, but that was not all. Vigilance committees also provided the fugitives with food and lodging and also were able to find them jobs and settle into a new home and life as a freed person.

Majority of the people who worked on the Railroad as “conductors” were free blacks, and they would often disguise themselves as slaves to help others escape. There were some white abolitionists and people who worked on the railroad, but not many. They would, however, be able to provide fugitives with food and a place to rest. Of the many “conductors”, Harriet Tubman is by far the most notable and remembered for making an estimated nineteen trips and aiding over three-hundred slaves. Even after the Civil War ended and the Railroad was no longer used, she, as did many others, continued to aid former slaves and would let them stay at her home. Levi Coffin is another who was involved with the Railroad, earning him the nickname “President of the Underground Railroad”. His home was even called “Grand Central Station of the underground Railroad”. Coffin aided more than 3,000 fugitives. John Fairfield, also a “conductor”, was known for his unusual methods of helping fugitives. He was born to slaveholder parents, but disagreed with their beliefs from a young age. William Seward, the governor of New York, even encouraged the railroad and housed fugitives in his home after the 1850 law was passed.

The exact numbers are unknown, but at least 30,000 escaped slaves were able to escape to Canada where all slavery was illegal. Perhaps more than 100,000 people were able to though. Many settled into Ontario, where many black communities began to from. There were several different rural villages in Kent and Essex counties where mainly former slaves resided in. An estimated 30 fugitive slaves daily crossed over to Fort Malden, the “chief place of entry” for fugitives who wished to go to Canada, on steamboat. Nova Scotia was another destination for escaped slaves. Following the American Revolutionary War, many blacks who were loyalists had moved there to their own settlements. Nova Scotia and Ontario were not the only places in Canada they escaped to, but also Quebec (then Lower Canada) and Vancouver Island.

While the desired location was Canada, slaves also escaped to free northern states. In 1789, there were only five free states and eight slave states. These free states included Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire Vermont Republic. It was soon after banned in New York and New Jersey. By 1861, there were fifteen slave states and nineteen free states before slavery was ultimately banned in the U.S. Other destinations include Mexico and the Caribbean, though mainly fugitives escaped to Canada and free states via the Underground Railroad.

The Underground Railroad was perhaps not as secret as people think. Though “conductors preferred to keep their identities and the Railroad secret, it was not uncommon for many white abolitionists to brag about it, and even publish articles in newspapers about how they aided slaves in escaping and how many. So really, it was not as secret as many believed, or wished for it to be.