PHOTO: newsweek.com

This year’s eclipse was captured by millions of people with their smartphones and cameras. For a few minutes, it felt like the whole world was looking up. Nearly 900 years ago, another solar eclipse passed over North America. In the absence of modern equipment to record the event, the people of the Chaco Canyon engraved a petroglyph on a free-standing rock known as the Piedra del Sol. Archaeologists believe the rock itself has always had ritual significance to the people of the Chaco Canyon. On its east side, there’s a carving of a spiral that marks sunrise 15 to 17 days before summer solstice. Archaeologists believe the Piedra del Sol was used to count down to the solstice celebration.

It seems only natural that the rock was used to record other important celestial events – like the total solar eclipse of 1097 AD.

The rock carving of the eclipse on the Piedra del Sol was first discovered in 1992 by Professor James Judge. It was carved by early Pueblo people, who made their home in the Chaco Canyon in the American Southwest. The canyon itself was populated by several thousand people, and influenced an area twice the size of the state of Ohio. The Chaco Canyon civilization began in the mid 800s and lasted for over 300 years. They built sophisticated, planned cities comprised of great houses, water control devices, and astronomical markers like the Piedra del Sol. Chaco Canyon became a center for public life of several Native American tribes, including the Navajo, who gathered regularly to trade and hold religious ceremonies at important annual events.

These were the people who watched and recorded the total solar eclipse that passed over North America in 1097 AD, just thirty-one years after William the Conqueror became King of England after the Battle of Hastings.

PHOTO: newsweek.com

Professor J. McKim Malville of the University of Colorado Boulder was one of the archaeologists who originally discovered the petroglyph on the Piedra del Sol.

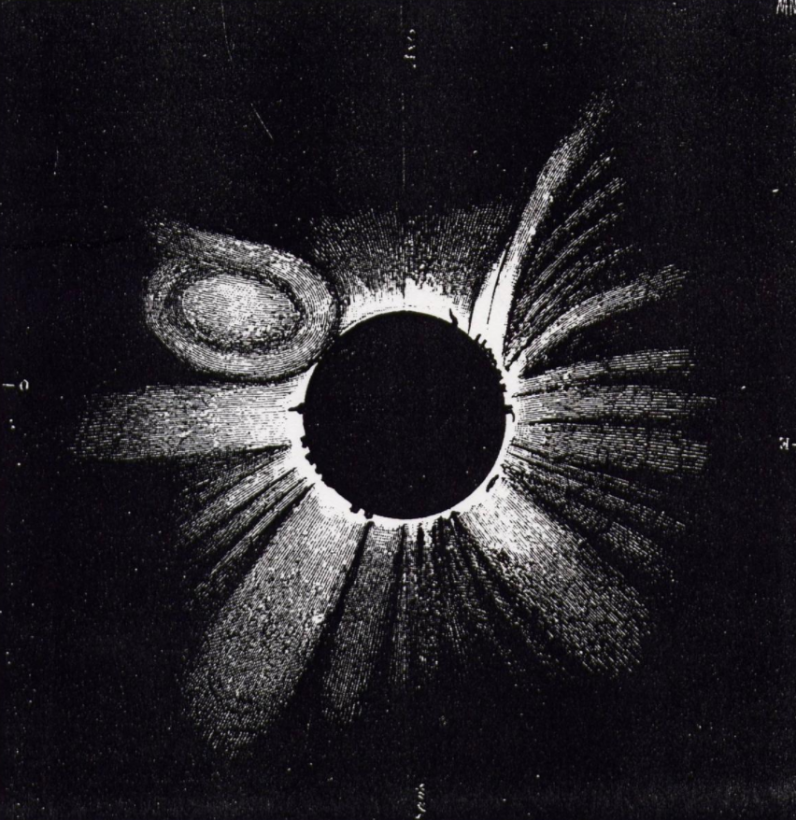

“To me it looks like a circular feature with curved tangles and structures,” he said, “If one looks at a drawing by a German astronomer of the 1860 total solar eclipse during high solar activity, rays and loops similar to those depicted in the Chaco petroglyph are visible.”

Along with the help of José Vaquero of the University of Extremadura in Cáceres, Spain, Malville was able to date the Chaco petroglyph to a period of time where there was “very high solar activity”.

The two compiled several sources about the activity of the sun around the 1097 eclipse. They looked at ancient tree rings to tell them the activity of cosmic rays, and used ancient Chinese records of naked-eye observations of sunspots. They also looked at historical information recorded by Europeans on “auroral nights”, when the northern lights were visible – another strong indicator of intense solar activity.

Based on all this evidence, they believe that this rock carving does indeed record the total solar eclipse of 1097 AD. It was a time of high solar activity – a time that the people of the Chaco Canyon would have been paying attention to for ritual purposes.

Such a cosmic event only happens once in a lifetime. It’s little wonder that they found a way to record it for their posterity.

Professor Malville and José Vaquero first published their findings in a 2014 paper for the Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry.